There’s a relentless, ongoing debate on the new norm that will define the way we live in the post-Covid-19 era. Never before has the emphasis on urban planning or the lack of it been more pronounced than in a world devastated by the ravaging effects of the pandemic in every sense of the word – economically, physically, and psychologically.

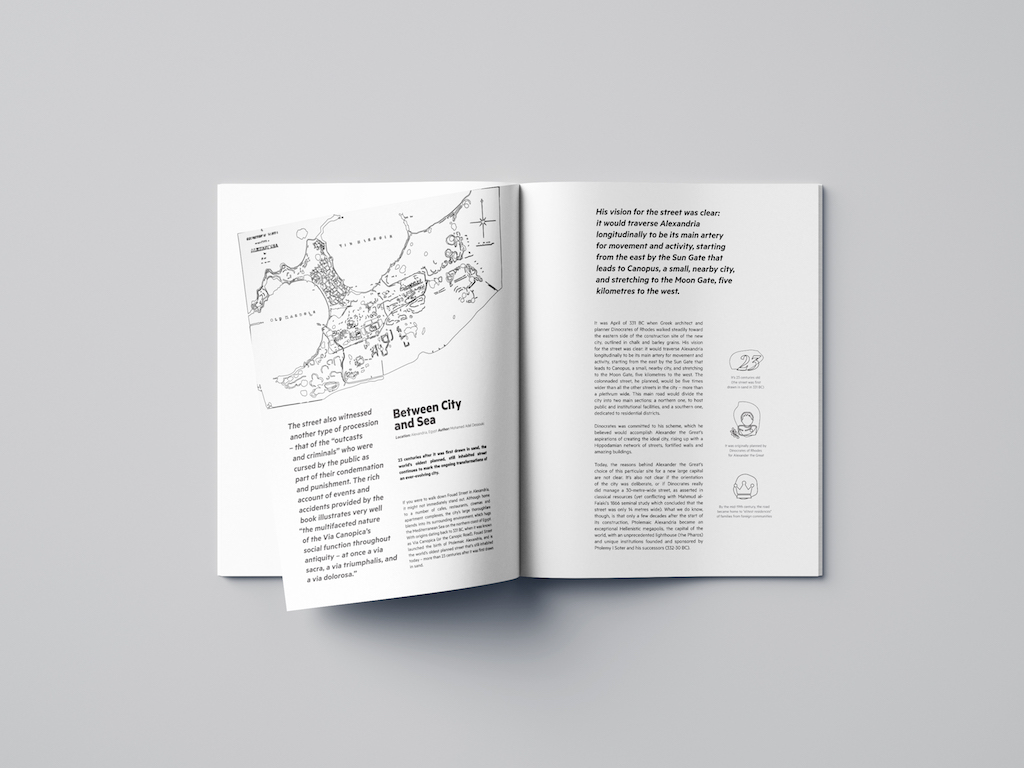

Recently, Hong Kong-headquartered leading global architecture practice LWK + PARTNERS, with offices and projects spanning several sectors around the world, launched an open-source research journal titled Red Envelope (above). The publication aims to initiate meaningful conversations on what makes cities work successfully, albeit without a cookie-cutter formula. This repository of urban ideas and essays from cities around the world humanise built environment using a deconstructivist approach. As such, it peels back the layers of gleaming, modern metropolises while celebrating urban towns and their people who have efficiently used resources – both tangible and influenced by socio-cultural context – to create places that are devoid of superficiality but work as well as they should.

But what happens when you throw in a pandemic and other natural disasters? Is there a formula that cities can embrace to respond to the challenges at play? The Red Envelope not only presents relevant case studies from the recent past, but also those dating back 23 centuries – Fouad Street in the Egyptian city of Alexandria is largely regarded as the world’s oldest planned, continuously inhabited city. As detailed in the publication, the rise and fall of this great Greco-Roman centre of power offers important lessons that are perhaps as relevant today as they were thousands of years ago, largely because humankind’s primal needs and aspirations for a safe, secure and well-governed state have not changed a great deal since then. We will cover some of these discussions in an ongoing series of interviews with architects and intellectuals who offer a new perspective from some of the most “unexpectedly progressive” cities around the world.

Kerem Cengiz, managing director, MENA, LWK + PARTNERS

Kerem Cengiz, managing director, MENA, LWK + PARTNERS

In an exclusive interview with DE51GN, Kerem Cengiz, managing partner, LWK + PARTNERS, who steered the publication, discusses some pertinent points on sustainable urban development that needs to be re-calibrated for more inclusivity and community involvement.

In this journal, you’ve compiled urban case studies from some of the oldest inhabited cities. What lessons can we take away from them in the current context?

Several of the pieces in the Red Envelope are indeed historical examples of the significance of urban planning and their societal effects, which often are not on the broader development agenda with reference to contemporary developments on the scale of the city.

The thread that runs through the journal is the analysis that our disparate urban environments are not only shaped by precepts of design but by unpredictable disasters be they natural or manmade – as was expounded by LWK + PARTNERS’ design director Kourosh Salehi’s practical and pragmatic views – that are significant for the future.

Each city is unique, it faces different impacts, shaped by fundamental structural issues such as social inequalities, war, diseases, economics, and extreme climate events, to name a few. It is arguable those hardest hit are the vulnerable populations in informal settlements rather than long-established urban centres.

We believe that as a global community we all need to re-establish our ‘collective’ attitude to social interaction in the urban environment and remain confident that not only professionals such as urban planners and architects, can and need to contribute to the debate but more importantly, the incorporation and enfolding of citizens in the debate within a structured framework can lead to unconstrained and interesting ways of creating, responsive and effective ‘partnerships’ within our cities and how they evolve while responding correspondingly and staying relevant.

“Several of the pieces in the Red Envelope are indeed historical examples of the significance of urban planning and their societal effects, which often are not on the broader development agenda with reference to contemporary developments on the scale of the city.” Kerem Cengiz, managing partner, MENA, LWK + PARTNERS

With the new density norms, how will urban design be impacted? Is the “density for sustainability” idea even valid now?

This is a germane question to consider at this juncture, there is no simple or single answer. The preception that density is a key quality for sustainability in terms of resource use in urban centres very much depends on how density is planned for and managed, it necessarily varies in its socio-economic and socio-cultural context.

We see in many urban conurbations that excessively high density, poorly-managed environments can negatively impact the health and social sustainability of a city and its citizens. Poorly managed density leads to overcrowding and excessive strain on a city’s infrastructures, particularly in times of ‘crisis’. The converse, low-density urban sprawl equally strains a city’s infrastructures and exerts its own pressures during these times.

Crisis comes in many forms; the current pandemic has highlighted that no one approach to urbanisation is better than another.

Vertical cities propound one potential solution – increase density in cities to maximise efficiency in mobility, infrastructure and metropolitan services. Hong Kong is such an example and in comparison, to other super-dense conurbations has been relatively unscathed by the current global pandemic, why is this? Is its good urban planning, governance or cultural?

It has drawbacks – not everyone is interested in this type of environment or lifestyle, and it can present health challenges. Respiratory infections are more prevalent in high-rise buildings as we are seeing in other such cities around the world.

Striking a balance between efficiency and quality of life lies at the heart of the question; high-density, low-rise development is the ideal for ‘density for sustainability’. However, what is the new norm, what does this actually mean, has there ever been a norm to deviate from? Perhaps as a global community, we all need to re-calibrate our collective attitude to the urban environment and respond contextually to the evolution of our cities.

“One certainty remains: Our urban environments will become increasingly denser despite Covid-19 or other disasters, and the management to increase the sustainability of our urban environments, improve quality of life, and decrease the negative effects of overcrowding will not and should not be in the hands of urban planners alone.” – Kerem Cengiz, managing partner, LWK + PARTNERS

Are urban planners out of sync with rapidly evolving cities, population and socio-cultural dynamics?

It would perhaps be a little disingenuous to assert this statement. Population growth and migration are global urbanisation realities; often driven by economic planning and human necessity, largely out of the hands of planners who are trying to respond, in some cases to unprecedented change.

It is predicted that around 70% of the world’s population will live in cities by 2050, it’s important not to consider urban planning as a one size fits all approach or panacea to socio-cultural or economic issues, there will be good and less successful solutions, as there always have been and will continue to be the case; we all need to play our part and take responsibility.

One certainty remains: Our urban environments will become increasingly denser despite Covid-19 or other disasters, and the management to increase the sustainability of our urban environments, improve quality of life, and decrease the negative effects of overcrowding will not and should not be in the hands of urban planners alone.

It still remains a truism that the most successful places are those that have responded most successfully to the contextual need of their inhabitants at any given period in history, they are dynamic organisms that respond and flex in good and bad times – they are resilient. This resilience is what urban planning should seek to instill.

You have pointed out that not all cities are created equal and there’s no formula for a well-planned city. Does this mean that community involvement leads to an organic city, and what do building and planning codes mean in this case?

Historically, community involvement has been an essential component in the successful creation and long-term governance of responsive and sustainable cities. This is not a new phenomenon. On the contrary, throughout history, when citizens are included, empowered, and allowed to take ‘ownership’ of what the regulatory framework represents, and contribute to their formation, the implementation of such frameworks becomes a natural and inclusive aspect of the creation of the urban fabric.

It is a common belief among leading commentators across the industry that the legislative ‘today’ we all now face, would benefit from the ‘creative deconstruction’ of the received models of thought around urbanisation. The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals may be a good starting point, wherein, I paraphrase ‘Make cities inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable’. Inclusivity has, unfortunately, been a secondary consideration in the decision-making process of the rapid and commercialised urbanisation of our cities.

Our cities are the collective ‘players’ of the living, working and consumption conditions of the world’s populations. The point being made in the foreword to the Red Envelope alludes to a need for cities to be places where we seek to overcome the divide between developed and developing nations, and the appropriate approaches we may wish to adopt.

Global inequalities are growing in many different respects and cities are the mirror of such in an unequal world. How we choose to respond to the risks of divergence is an objective that legislators and policymakers must address along with how to encourage citizen ownership and participation. Greater involvement of the community in the formation of our urban fabric, would greatly enhance the creation of better cities and mitigate the risk of divergence in our societies.

Photos courtesy: LWK + PARTNERS

You might also like: