Indonesia recently announced its plans to relocate its capital from Jakarta on Java Island to East Kalimantan citing reasons such as congestion and polluted waterways. These urban challenges plaguing the Indonesian capital convinced President Jokowi Widodo and his administration to undertake the herculean task of relocating the capital hundreds of miles away to a yet-to-be-built city. While the idea had been mooted by several Indonesian Presidents over the years, it has only been approved by the country’s parliament now.

President Jokowi had said during a press conference last year: “The government has conducted in-depth studies in the past three years and as a result of those studies, the new capital will be built in part of North Penajam Paser regency and part of Kutai Kertanegara regency in East Kalimantan.”

In a contest organised late last year, architectural and urban planning firm Urban+’s entry for Indonesia’s new capital won the high profile project. The practice’s founder Mr Sibarani Sofian envisages a compact downtown core that will allow a resident to walk from a cluster of housing down a generous boulevard through the business district to the presidential palace in the north in about an hour. The masterplan also includes a mass transit system consisting of an electric tram network that can be replaced with an MRT network or a light rail later. Other features include drones for package delivery and generous pavements.

It’s hoped that the $US33 billion project will ease the pressure on the polluted, sinking and overpopulated capital of Jakarta, home to 30 million people. While the new capital city was expected to start in the first phase of infrastructure development for the new capital in the second half of this year with a “soft ground-breaking”. The completion date was set for 2024 — the final year of Mr Widodo’s term – but it is now anticipated that it’ll take longer than expected as the current pandemic has halted the ambitious project. By 2045, it’s expected that the new green capital city, for which some 180,000 ha of scenic government land has been set aside, will be fully functioning. The location in East Kalimantan was said to be particularly preferred Mr Widodo for its low natural disaster risk and pre-existing nearby infrastructure. However, challenges abound.

East Kalimantan’s native fauna has orangutans, sun bears, and long-nosed monkeys, some of which are already threatened by the pollution from coal mining and palm oil plantations. The area also houses more than 1,700 former coal mines that have left behind massive holes, which will need to be filled up before construction begins.

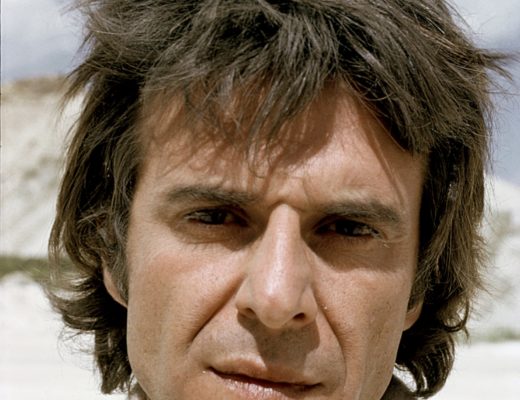

In an exclusive intervirew, DE51GN speaks to Mr Sofian – whose stellar professional career includes senior roles at top firms such as RSP Architects, Planners and Engineers, Skidmore, Owings and Merrill, EDAW and AECOM where he oversaw projects across Southeast Asia, India, China, Taiwan and South Korea before founding his practice in 2016 – about the challenges and opportunities involved in one of the biggest projects on the anvil in the region which could possibly set an example for other countries in the region that are mulling over a similar idea.

The shifting of Indonesia’s capital from Jakarta to East Kalimantan is one of the biggest projects undertaken in recent times in the region. How is this going to impact Jakarta once the move is completed?

We think that the capital relocation is actually a complementary thing. It will re-balance the already congested Java island and start to put more emphasis on other islands in Indonesia. We’re an archipelago country with 17,000 islands but more than 56% of the national economy of the nation is centralised in just one island – Java. The capital relocation will indeed impact Java and particularly Jakarta, but in the longer-term, it’s going to be better for the whole country’s perspective. Jakarta is still going to play a major role as the business and financial capital of Indonesia, but the administrative capital will be in East Kalimantan.

What really entails setting up a whole new capital city and how many years do you reckon it will take before it starts developing organically?

We’re at the planning stage at the moment, and it will take sometime before we start to develop the capital city. Ideally, we have more time, if indeed looking at other similar capital city relocations such as Canberra, Putrajaya, and Astana, a period of five years in planning will be minimum. However, the current administration is putting this five-year plan on the fast track, in which we’re planning while also progressing on the site. Prior to Covid-19, the original plan was to have something started to be developed in Pasir Penajam East Kalimantan in 2024. This means, we have to work very fast starting now till 2024 but now with Covid-19 taking place, the plan and schedule may need to be reviewed again soon.

What factors did you keep in mind for Nagara Rimba Nusa concept for the new capital? How will it embrace sustainability?

When we visited the site during the competition back in October 2019, we realised that the site is very much still open and green, dominated by productive forest (not natural/primary forest), we were inspired by the fact that the area is very much related to water (balikpapan bay in Bhasa) and the idea of Nagara Rimba Nusa (nagara means city/government, rimba means forest and nusa means islands) came about knowing that the relocation of the capital city will bring the government and city into a natural setting of Borneo which is characterised by “rimba” and it needs to embrace the identity of our nation, Indonesia, which is characterised by archipelago or “nusa” in its essence.

Embedded within the Nagara Rimba Nusa, is the notion of creating a harmonious relationship between man, nature and our relationship with God. Indonesia has a common spatial philosophy of this notion, that is Tri Hita Karana in Bali or Tri Tangtu in Sundanese culture, or Catur Gatra Tunggal in Javanese Culture. They are deeply rooted in our culture and it has become part of the Indonesian way of life, although, in current times, people tend to often forget about them. The Nagara Rimba Nusa seeks to rediscover and bring this philosophy back to life.

This goes beyond sustainability – it’s an embodiment of our well-being and way of life that respects and is inspired by nature. In our scheme, we proposed to create an urban concept of bio-mimicry which attempts to imitate and adapt the forest into a man-made development.

Are there any important lessons learnt from Jakarta’s climate impact which you have considered in the new city?

Understanding that the site in new the capital city is way more humid and harsh than Jakarta, we need to work harder in creating a better climatic condition there. We proposed a walkable city that strives to reduce the use of personal vehicles, and in order to achieve this, we need to create a built environment that promotes walkability. This requires a holistic green approach that attempts to create a reduction in heat island effect which usually happens in an urban area. This involves the creation of a large green and blue oasis in the centre of the city which we aim to achieve by placing a botanical garden in the centre of the city as well as a forest reserve and wetland conservation areas surrounding the city. This effort, combined with wind movement, potentially will help in better wind flow and breeze in the city’s road and pedestrian corridor, with the hope to bring down the temperature and humidity to allow a comfortable walking environment.

In light of the new development– the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic – how do you think urban masterplans will evolve? Is this something you are going to incorporate into the new capital?

We are fully aware that Covid-19 is the big elephant in the room that needs addressing, and yet, here we are still trying to grasp the phenomenon and seeking to find the pandemic’s real consequences to the urban environment. Should we refrain from the social gathering spaces that we traditionally encourage in urban design? Should we prevent people from taking shared transportation modes? Should we reduce attendance at festivals and cultural events, religious sites, and tourist spots which usually gather a lot of people in public space at the same time?

This remains a point of discussion and discourse for the future, new normal-post Covid-19 world. However, we can take away a few things from this event: People’s awareness and expectations towards public hygiene will be higher. Government and town managers need to accommodate this into the new standard in the future.

Role of technology and communications about prevention, mitigation, tracking, information sharing related to the future spread, and the potential emergence of future infectious diseases will hold much higher importance henceforth. Cities should equip themselves with the capacity to address all of these challenges.

The ability for a city to quickly shift its functioning to work around any disaster or pandemic and still keep up the economic activities; the ability for the city to quickly bounce back and reverse back to normal after the challenging situation is over will need to be part of urban planning. For example, having online delivery and logistics, online conference, and the flexibility to work from home. One keyword that we must become more familiar with is resiliency.

“Jakarta needs to quickly rejuvenate its ageing infrastructure, prevent further land subsidence, increase capacity in handling flood and increasing sea rise level, push shift to public transport, increase the level of service, continue developing robust pedestrian and walking infrastructure, while opening a new paradigm of urbanism that promotes high performance, efficient, mix and high-intensity urban centers around key mass transit point, while allowing an increase in urban greenery to higher levels (beyond the current 9%).” – Sibarani Sofian

How can Jakarta be rejuvenated? Can better urban planning from here on alleviate some of its pain points?

Jakarta should take this capital relocation event as a golden opportunity to rejuvenate and redevelop. On one hand, the city will lose one of the functions – administrative. But, on the other hand, Jakarta will have less traffic and burden of people. There is a narrative to release the various government sites in Jakarta to partially fund the development of the new capital city. This needs to be carefully managed by the Jakarta province with close coordination with the national government.

Jakarta needs to quickly rejuvenate its ageing infrastructure, prevent further land subsidence, increase capacity in handling flood and increasing sea rise level, push a shift to public transport, increase the level of service, continue developing robust pedestrian and walking infrastructure, while opening a new paradigm of urbanism that promotes high performance, efficient, mix and high-intensity urban centers around key mass transit point, while allowing an increase in urban greenery to higher levels (beyond the current 9%). This can be combined with the potential location of the government sites that will be released for development. A careful and strategic urban planning and development scenario between Jakarta and the future capital city need to be established and developed by relevant authorities and stakeholders.

Since Jakarta is facing the sinking issue due to congestion and overcrowding, do you reckon urban sprawl is the solution – moving away from concentrated nodes of business and commercial activities? In that case, how does the theory of “dense is greener” come into play?

The sinking of Jakarta is related to various factors. Overcrowding and over-congestion are not necessarily the highest contributing factors. One aspect that people point out is the massive extraction of deep groundwater with very limited ability to replenish it due to lack of greenery and in the case of some coastal areas, the infiltration of ocean water. With the hollowing underground cavern, the ground may be subsiding especially if heavy structure and load-bearing (such as high rise buildings) are above it. So, the solution should not be a singular act of decentralising, but according to our study in North Jakarta area (we are currently working on Jakarta MRT Study of Mangga Dua and Ancol area), the mitigation efforts should be in several sequences of action.

We drew case studies of several sinking cities such as Tokyo and Shanghai. We observed that these cases suggest somewhat similar actions as follows : 1) Immediate stop to groundwater intake, both deep or shallow well, while providing reliable municipality water supply to cater to people’s need of water. 2) Temporary stop to further increase in development, while waiting for healing/intervention. 3) Intervention to provide immediate recharge/infill to the hollow ground cavern (this can be done through various technologies such as injection or vertical drainage to immediately recharge the water (further study and reference needed here). 4) If the ground subsidence has already stopped, then the development can be reorganised where one option is to have higher density combine with higher green ratio. This should be done with the understanding that rejuvenating decaying or failing infrastructure will require a lot of investment which may not be all covered by government budget.

What have been some of your key takeaways from other urban cities which you will reinterpret in the context of the new Indonesian capital?

We’d like to see that the new capital city brings a new paradigm, new model, and new standards for other cities in Indonesia. Our current paradigm of city and town making and managing in Indonesia, in my personal opinion, has not developed much since our independence. We are reacting to the condition and challenges facing the city starting from the day we became independent.

We should be ahead of the curve, anticipating instead of reacting. There is no evidence that the current paradigm of the city today in Indonesia has produced a good city. In my personal observation, we are quite behind on this due to lack of knowledge, know-how and courage to create a new model and breakthrough that strives for a better city. Our government and city regulation came from the paradigm of regulating and protecting, not exploring and innovating. We are now in 2020, not 1945, and surely certain things have changed. We should be able to not only deal with current issues but also be able to cope with future challenges.

“The sinking of Jakarta is related to various factors. Overcrowding and over-congestion are not necessarily the highest contributing factors. One aspect that people point out is the massive extraction of deep groundwater with very limited ability to replenish it due to lack of greenery and in the case of some coastal areas, the infiltration of ocean water.” – Sibarani Sofian

Do you foresee other countries in the region who might consider shifting their capital city?

Honestly, I can’t really see that far towards other countries. We are still struggling to digest this relocation city for our own country, looking into another country is still not on our horizon yet. But, I can see how other similar developing countries may be inspired to do the same. The pull factor of our move is the inequality and unbalanced development of one area/island/region compared to others. Another push factor for us is the sinking and failing of our current capital city. A major factor that comes to play is the leadership and confidence that the current administration may have in creating such a legacy project. Any country that has somewhat similar motives, situations, or backgrounds like ours may follow suit.

Which urban city in the world do you admire for its long-term vision towards the built environment?

There is no single city that I can singularly point out as a model of an ideal city, but if you ask me particularly on the “long-term vision”, the obvious choice is Singapore. But one really needs to realise, that Singapore is a city-state, with very specific conditions and geographical set up which is hardly easy to find parallels of. Some aspects and isolated cases may be referenced, but in terms of how and what it takes to make it happen, Singapore has quite a particular set up (be it political, administrative, as well as budgetary) that can’t be repeated by others. But personally for me, being a resident in Singapore for about 10 years of my life, I really enjoy it and a lot of things can be learnt from Singapore. Other cities which I usually like to refer to for Jakarta are Sydney, Hong Kong, Kuala Lumpur, and Tokyo. Certain we can learn bits and pieces from these cities that can make up a series of learning lessons for an urban city in Indonesia.

You might also like:

“Indonesian capital move to Borneo will also shift its creative industry,” says Lim Masulin

Andra Matin retrospective marks 20 years of Indonesian architect’s practice

Construction begins on new smart green city in Philippines masterplanned by Broadway Malyan