Marwa Al-Sabouni is a Syrian architect and academic who authored the book The Battle for Home: The Vision of a Young Architect in Syria which explores the role of architecture in building neighbourhoods and communities and social cohesion. Written when the Syrian civil war was at its peak, her book has garnered critical acclaim by academics, architects as well as readers in general. Born, raised and educated in Syria, Ms Al-Sabouni, 39, lives in Damascus with her architect husband two children aged 15 and 12. In an exclusive interview with DE51GN, Ms Al-Sabouni shares how she and her family held it together even in the darkest days and how architecture emerged as a protagonist in the Syrian civil war – the key to keeping or destroying neighbourhoods.

Is it common to find female architects in Syria considering it still remains a male-dominated profession, not just in conservative countries but worldwide?

Contrary to perception, female architects in Syria are not uncommon to find. In Syria, there has always been a balance. When I studied architecture, it was 70% females to 30% of male students in the class. However, despite being a female-dominated discipline, the commissions are more likely to go to men because of various reasons but mostly because it is perceived that men can manage worksites more efficiently and deal with the construction workers more effectively. The site workers tend to challenge female architects and their authority.

Did you always want to be an architect? What influenced your decision?

There was a socio-cultural factor at play when I decided to become an architect. While growing up, it wasn’t clear that I wanted to be an architect. Most Syrian students, if you do a survey among them, don’t know what they want to be and their future vocation. One element is that the A’level examination in Syria is a milestone that is almost life-destroying because it’s difficult to pass. you need to score almost between 90 and 99% to have an acceptable college degree. Families self-isolate before the exams or hire a team of private tutors for their children. The emphasis on passing the exams with good score is too high. My decision to study architecture is basically due to the grades that I scored in my A’levels exam. Higher scores give you the option to study medicine or engineering. I wasn’t interested in those fields anyway. I was keen on pursuing a subject in the creative sector. But I can’t claim that I had even the slightest idea of what architects do.

“I must mention that most graduate architects don’t really have a chance in the industry because there is a sort of monopoly by big names and the Syrian market is dominated by a cluster of monopolies. It’s all about networks of strong businessmen, their affiliates, and partners. In that sense, those networks have their hands into public institutions which play out in relation to corruption and networking, and which is why all the big commissions are pre-decided as in who will work on it.” – Marwa Al-Sabouni

Do you ever rue the fact that you have not been able to practice as an architect due to the situation in Syria? How do young architects like yourself cope with it?

I was only 29 when the war in Syria started when I was working as an apprentice in an architecture firm run by my husband. I was just beginning to take the first few steps forward in my career when it was interrupted by the war. I was also pursuing my master’s at the time and later I studied PhD. I was pursuing more of an academic career than a practice. I had no real chance to practice. I must mention that most graduate architects don’t really have a chance in the industry because there is a sort of monopoly by big names and the Syrian market is dominated by a cluster of monopolies. It’s all about networks of strong businessmen, their affiliates, and partners. In that sense, those networks have their hands into public institutions which play out in relation to corruption and networking, and which is why all the big commissions are pre-decided as in who will work on it.

This is one of the reasons why most of my colleagues and peers have immigrated to Western countries or the Gulf countries right after graduation because not being part of the “inner circle” we don’t stand a chance. It presented a very grim future and in that sense also, I had no chance of getting any commissions.

For Syrians, immigration is a persistent topic of conversation and it is something that everyone talks about. The present circumstances of the blocked horizon will persist for generations not just now. Growing up, one would always hear from seniors or friends who had graduated where they would be discussing options of immigration and perhaps landing scholarships in the West in the middle of their studies. The idea of graduating and pursuing a career locally is almost unfathomable. Either you have a network to support you or one that your family is part of, else the only other option is you move out of the country. Both my husband and I had neither of those options. Many of our colleagues thought we were foolish. They’d never understand why both my husband and I, who were distinguished students at university, will not take that opportunity.

I have found hope in my faith and we believe in our existence and that we’re here for a reason. I tell my children to worry about their own actions and never about others’ actions. Whatever you can change is your responsibility and what is beyond your control and ability to change and make good, is not something you should worry about. We take hope in that. My biggest responsibility as a parent is to enable my children to make the right choices even as we live in a world where a lot of wrong passes off for right. As a mother, the most important role for me is to hold a moral compass and keep my children safe and secure, and make them strong individuals so that they can continue to uphold this moral compass. My hope is that I have created whatever is possible within my means to make it a reality for them.

Urban planners, architects and other stakeholders are now talking about rebuilding or reinventing cities post Covid-19. But in Syria, which has experienced years of strife and civil unrest, what does rebuilding mean?

It can’t be pre-defined in a formula – it’s not one size that fits all. It has to be a process that looks at micro-places within cities and considers all the social, historical, and economic factors and then look at rebuilding. To me, rebuilding is not a process that is a tabula rasa, a place that is completely cleared out of elements and starting over. Rebuilding is about picking up indicators from the surroundings and the environment that is going to be rebuilt and be super-sensitive towards those elements and find a way to intertwine them into something that is relevant to its past including the most recent past. It needs to be relevant to what was there before. It’s something that needs to be done with sensitivity and a clear vision of what attributes and programmes you want to enable in that place. It’s basically answering the right questions.

How is architecture entwined with the lives of Syrian people? What place does architecture have in Syrian society and what sort of socio-psychological effect the widespread destruction has had on its people?

In one word, despair. It’s the most common mood. It’s very dangerous to have despair because when people lose hope, they are willing to make all the wrong choices because it doesn’t matter anymore. Right now, Syrians are not concerned anymore with anything that doesn’t impact their daily living. Currently, we are challenged in our everyday lives. People are facing famine at the moment. Over 80% of the Syrian population lives below the poverty line.

Things have changed radically for Syria. It was a place where heritage, civilisation and fertile lands were taken for granted for a very long time. It changed over the past decade due to war and destruction. The national division, internal corruption, and international politics have played on this burnt stage. It’s very frustrating and sad. People see our currency taking a hard hit and being devalued due to the Covid-19 situation, American sanctions, and internal problems that we have.

People just talk about how they’re going to live to see the next day. Everything has stopped. All the businesses have closed. People are looking for means of living. Building materials are not available, prices are undefined, and there is no business taking place. It’s a very difficult situation. But the role of architecture is something that always plays in the background of everything happening. It is related to real estate, where people live, how people belong, the sense of neighbourliness, and the relationships among communities as well as enabling local economies and all of that.

But at the moment, we are barely surviving. We don’t know what tomorrow will bring. It’s a bleak picture but the human instinct is to move on. Eventually, things will have to work out and we will have to move out of this deadlock, but when that will happen remains to be seen.

What sort of urbanisation is taking place in Syria, if at all? Does it lean towards building or rebuilding infrastructure projects or the preservation of historic ruins that, if completely gone, will change the socio-cultural fabric of Syrian cities?

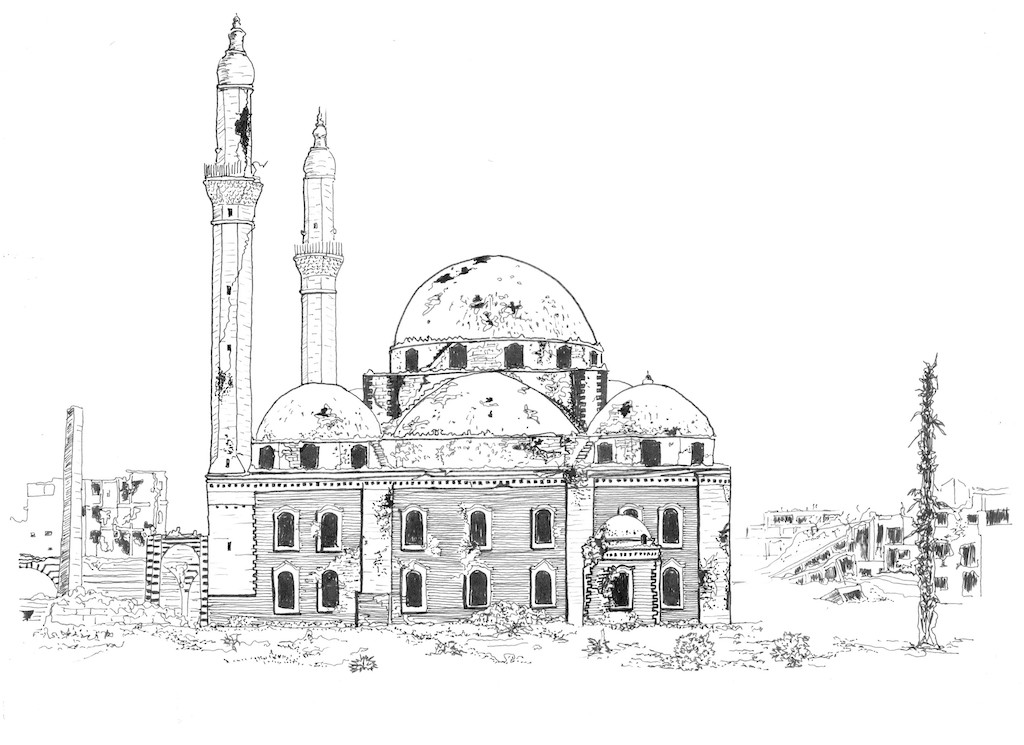

It’s another sad episode of the Syrian saga. More than 40,000 pieces of heritage locations were looted over these 10 years, and these are just the documented looted pieces. Thousands of archaeological sites were destroyed and dismantled and sold in the black market. Those priceless objects are lost forever. We live in a country that is severely wounded. We’ve lost lives, treasures, values, morals and so many invaluable things. I don’t know when this loss will stop and when we will begin to rebuild all of those.

Some things may have been lost forever and never be reclaimed but my hope is to revive the good old days and revive this place that has never stopped living. Damascus is known to be the oldest inhabited capital in the world continuously. I hope that doesn’t ever change. My hope is that the loss will stop and it’s our responsibility – on both local and international level – to do something about it and stop the hypocrisy. It’s difficult to see this.

In what ways are young Syrian architects keeping the architectural narrative alive and do they anticipate being part of rebuilding process of their country that includes not just brick and mortar building but also social reconstruction?

As I mentioned earlier, there is little chance for them to prove their potential. Despite that, everyone still hopes for change. If you’ve to worry about the future based on the current reality in Syria, I think most will contemplate committing suicide because of the all-round despair. But like I said, human nature is hopeful and if you have enough faith, you worry about what you can control and the rest will sort itself out hopefully in a positive way. When I taught at the university, this is what I told my students that when everything is so negative, people do tend to lose hope. But historically it is proven that positive change becomes a reality when everybody is convinced to change the little things they can within their purview without worrying about the big picture. So if everyone collectively does the right thing, I think there will be little space for the wrong to prevail. But if everyone gives up, then we would have enabled the wrong to prevail.

“Even during the darkest days of the war, I chose to keep busy. I was studying for my PhD and writing even when there was no electricity and we had blackouts and we basically gathered as a family around candlelights and the children would read stories, and my husband would read his books. We decided to make the most of whatever we had on our hands. It was the only way to survive, else you’d end up in a very dark place. I was inspired to write the book by the events that were taking place right outside my window. I saw the madness, people were flocking the area and killing each other.” – Marwa Al-Sabouni

What has kept you inspired all this while after having to shut down your practice when the war started?

Even during the darkest days of the [Syrian] war, I chose to keep busy. I was studying for my PhD and writing even when there was no electricity and we had blackouts. We basically gathered as a family around candlelights and the children would read stories, and my husband would read his books. We decided to make the most of whatever we had on our hands. It was the only way to survive, else you’d end up in a very dark place. I was inspired to write the book by the events that were taking place right outside my window. I saw the madness – people were flocking to the area and killing each other.

I was studying Islamic architecture at the time and it occurred to me why a certain group of people have certain reactions. Then it became clear that they all came from specific neighbourhoods and that label was attached to their collective behaviour which sparked the idea for the book – the place you come from impacts your collective consciousness and therefore, actions.

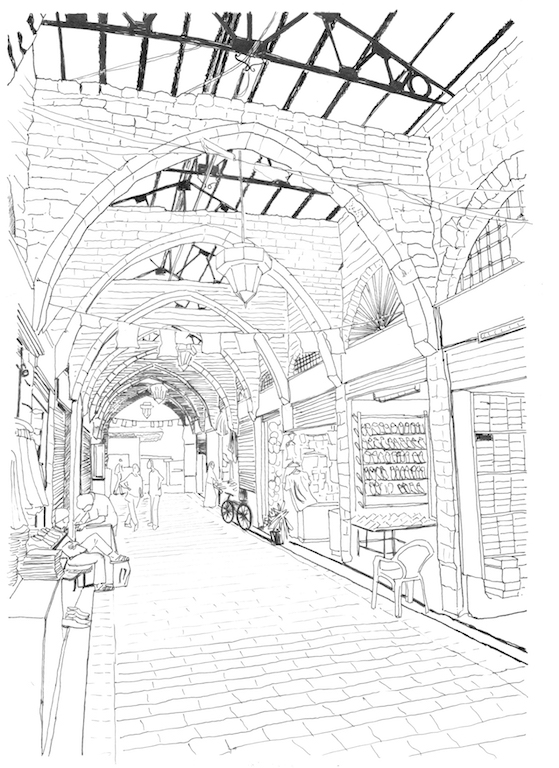

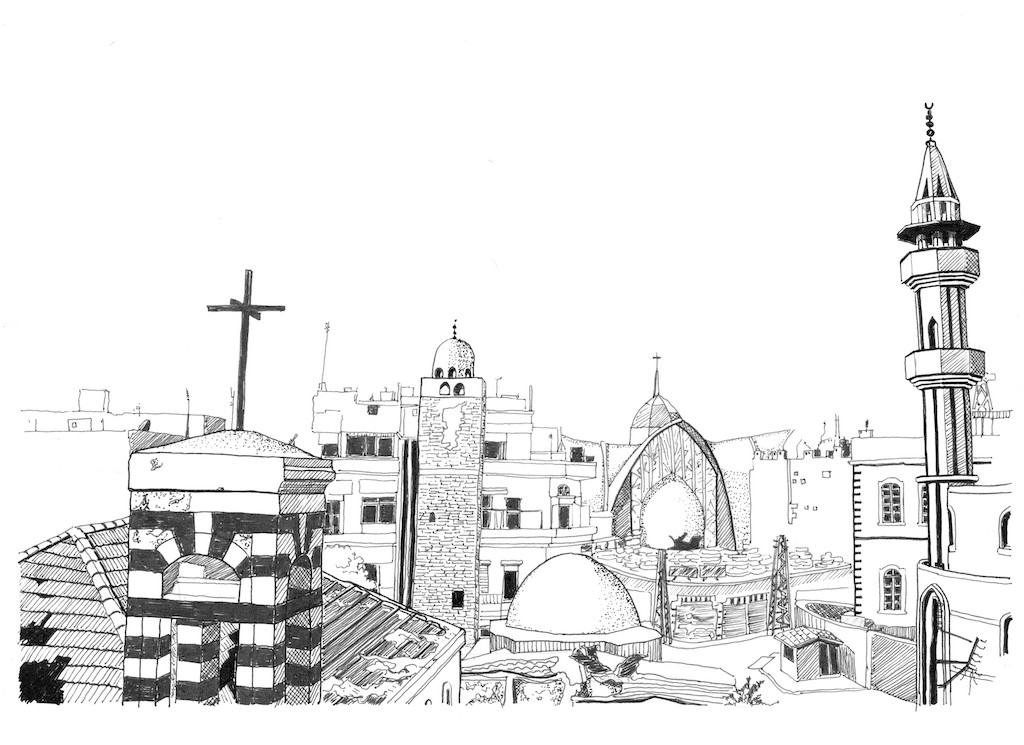

When I looked at my segregated city where a group of people from a certain neighbourhood were pitted against another group from a different neighbourhood, I realised that these people had actually never met each other. So there was a stereotyped image of what the other group could mean and do. Whereas comparing that to the old city where I live, you’d hear a completely different concept. People never worried about the backgrounds and religions, and they had mutual respect for each other. Trade relationships were defined in a way that enabled communal living and just meeting those people and hearing those testimonies, it became clear that behavioural patterns were specific to the backdrops of different areas of the city. The description of a place is very intrinsic to defining social relationships.

This is where the architects’ talent becomes a required condition. Architects should have the skill of not only creating aesthetic forms and implementing challenging structures, but they should also have this awareness of what they want to enable in a place and draw out the special characteristics of that place that are unique to it – characteristics that will make a place thrive or traits that contribute towards its deterioration. In this sense, architects also need to be social experts.

If there is one building you could design in your country, what will it be – such as school, library, housing?

I have to say that an architect sees the potential in any experience. No matter how big or small the scale. Architecture is a tool to look at the universe. It is always a kind of mathematical dilemma – like a riddle that you need to solve. So in that sense, every project has potential. I have a keen interest in designing parks and libraries because I love how these two places bring together the elements of nature and culture. They bring people together and bring forth the beauty of creation.

All images and illustrations courtesy: Marwa Al-Sabouni

You might also like:

World Refugee Day: Jan Rothuizen takes us inside Domiz refugee camp in Iraq