Spanning both material and intangible oeuvres, the Rohingya Cultural Memory Centre in Cox’s Bazaar highlights the richness of an oft-misunderstood culture in danger of being diminished. To mark the UN World Refugee Day on June 20, DE51GN examines the significant role that socio-cultural and educational initiatives play in giving hope to displaced communities.

By Cara Yap

For the most part, the discourse of displacement is mired in grim statistics: it’s estimated that close to a million ethnic Rohingya refugees are settled across a tangle of camps at Cox’s Bazar in south-east Bangladesh, with more than 700,000 having fled a deadly crackdown by Myanmar’s army in 2017.

Underlying the scourge of their mass exodus is the risk of detrimental psychosocial impact stemming from, among other factors, a loss of cultural identity. International Organization for Migration (IOM), a United Nations-affiliated intergovernmental agency that offers humanitarian support to Rohingya refugees dwelling in Cox’s Bazar, recognised this after conducting a 2018 assessment of their needs.

The study gave rise to the Rohingya Cultural Memory Centre (RCMC), a community space and digital gallery started with the aim of preserving cultural memories, traditions and practices. “There is a dominant narrative that the Rohingya are poor and simple village people who don’t really have art or a developed material culture, and we want to show the world that this is not true,” says Shahirah Majumdar, RCMC’s manager and editor.

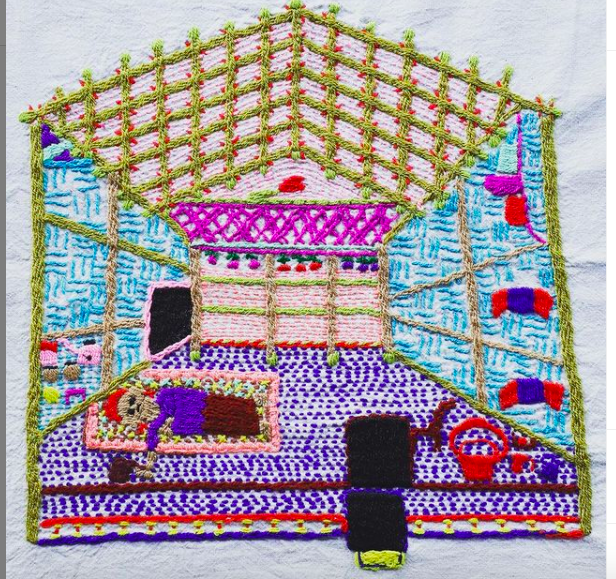

Among the artefacts the centre commissions Rohingya refugees to produce, are handwoven baskets and fishing contraptions, embroidery work, pottery and paintings. The artisans are remunerated for their work, which includes intangible cultural assets such as folk music, poetry and food. Curating this diverse compendium of work and unearthing their provenance entailed consultations with ordinary people and a degree of resourcefulness – considering the dearth of canonical references. This is owing to waves of migration over several decades; the Rohingya diaspora is dispersed across countries including Indonesia, Malaysia, Canada and Australia.

“There is a dominant narrative that the Rohingya are poor and simple village people who don’t really have art or a developed material culture, and we want to show the world that this is not true.”

Shahirah Majumdar, RCMC, manager and editor

“We gather groups of men and women separately and ask them to share their stories and knowledge. They won’t always agree with one another, and there will be some back and forth as names of things can vary by location and economic conditions, so we verify this over and over again,” explains Ms Majumdar. It’s a living project undergirded by “Rohingya people practising and documenting their own culture, rather than academics in ivory towers”.

Ms Majumdar shares that RCMC works with about 75 artisans, most of whom aren’t highly educated. The project, however, has assumed a life of its own, with calls for submissions disseminated freely by word of mouth through the sprawling but tightly-knit community. They have amassed close to 1,000 items, which are stored in warehouses outside the camps – following a conflagration that ripped through a section of the makeshift settlement this year.

Beyond the backdrop of penury, however, is the real threat of cultural dissipation. This is especially a concern, considering the people’s inability to practise their livelihoods – which include agriculture and fishing. Asylum seekers in Bangladesh are barred from working. “It is very important to have a cultural museum for our community. There are children who have lived here in the old register camp for the past 20 or 30 years. When they saw our cultural objects, they asked, what are these? because they had never seen anything like that before,” shares Nurul Islam, a 60-year-old Rohingya farmer skilled in the art of weaving.

The artisan crafted a woven model doloin, a hand- or cattle-operated rice threshing machine used by Rohingya farmers before they were mechanised, for the centre. “We are very happy to see our cultural heritage being kept alive at RCMC, for our children and future generations to learn about,” he says.

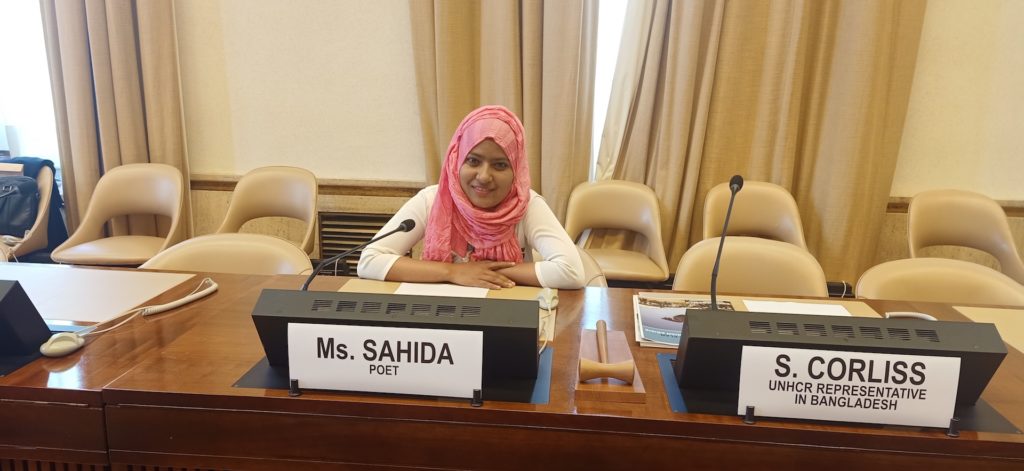

Another project partner determined to prevent Rohingya traditions from being consigned to the realm of fables is poet Shahida Win. The 24-year-old, who together with her family cut a narrow egress from Myanmar pursued by gunfire, describes a hardscrabble existence in a camp marked by overcrowding, widespread disease and deprivation. She writes as a form of expression and to voice her community’s culture and rights.

“A human being cannot forget his culture; if he does, he cannot be a human,” she asserts, adding that the centre helped revive aspects of Rohingya heritage that had all but vanished. “I’ve heard of the doloin, but never knew how it worked (till I viewed it in RCMC),” she shares. Interlaced in the young poet’s verses, is an impassioned plea for gender equality, and she hopes she can help alter patriarchal norms in her conservative culture.

Interestingly, the RCMC has also encouraged empowerment across gender and social lines. For instance, its embroidery workshops provided a cathartic outlet for its female artists, who gather to share personal experiences that are then stitched onto tapestries. They are trained by Bangladeshi artists who have helped them expand their artistic repertoire beyond traditional floral and faunal motifs, to include human depictions.

“A human being cannot forget his culture; if he does, he cannot be a human.”

Sahida Win, Rohingya poet and refugee

Ms Majumdar notes a distinct style that has taken shape in the Rohingya’s embroidery work, from their use of bright colours and thick thread, to unique human forms bearing details such as thanaka designs. “One of the wonderful things that have emerged is a specifically Rohingya aesthetic that they have ownership of,” she says.

If objects are a reification of social constructs, perhaps the value ascribed to RCMC’s commissioned pieces has helped to disabuse the community of long-held prejudices. Ms Majumdar shares the example of Rohingya potters, who prior to mass migration, lived in segregated and marginalised collectives of low social standing. While they were initially hesitant to overtly participate in the initiative, for fear of discrimination by the wider community, there has since been a shift in perspectives.

“As the objects they made were displayed, documented and verified, the value they place in their work and themselves has changed. They feel a sense of pride and are very happy to be seen working on these pots out in the open. We have people from the community coming by to view them, expressing how they miss the taste of water from a clay pot,” recalls Ms Majumdar.

“As the objects they [Rohingya potters] made were displayed, documented and verified, the value they place in their work and themselves has changed. They feel a sense of pride and are very happy to be seen working on these pots out in the open. We have people from the community coming by to view them, expressing how they miss the taste of water from a clay pot.”

Shahirah Majumdar, RCMC manager and editor

This heightened morale engendered by the project has caused a ripple effect. “One of our volunteers said to me that every ethnicity in Myanmar has an ethnographic museum, except for the Rohingya. The RCMC gives them so much dignity and pride which, unfortunately, have been in short supply in recent years,” she recounts.

While regulations prevent the artisans from selling their artwork in the market, there are plans to hold an international travelling exhibition. Also in the pipeline, is a physical centre to house the collection, built with vernacular design principles. With a proposed hilltop location, the “female-friendly space” will house an open-air auditorium, artisan’ workshops and an exhibition hall. Though impermanent, the multi-purpose complex is set to foster cultural activities for the Rohingya community, sparking creativity in stygian times.

All photos courtesy: Rohingya Cultural Memory Centre

About the author:

Cara Yap is a former travel editor who contributes pieces on thought leaders and social entrepreneurs to the likes of CNA Luxury and Singapore Magazine. She has a penchant for country roads that disappear into hills and end at the coast, plus cities with mouldering architecture. She is averse to minimalism; the curlicues and embellishments of the Art Nouveau style speak to her love of excess. When she is not covering in-depth human interest features and lifestyle pieces, Cara runs her backpacker’s hostel in Indonesia.

You might also like:

World Refugee Day: Jan Rothuizen takes us inside Domiz refugee camp in Iraq