Across India, more than 1.3 million Anganwadi Centres (AWC) provide children and women from low-income households with basic healthcare, preschool education and meals. Established in 1975 by the Indian government to alleviate childhood malnutrition and improve literacy, the childcare centres are typically utilitarian in design, with concrete walls, dirt floors and dimly lit, stuffy interiors.

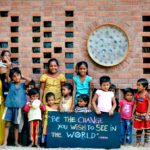

Enter The Anganwadi Project (TAP), an Australian non-government organisation (NGO) that has elevated the concept of the AWC by marrying form and function in ways that – in the highly marketable parlance of Marie Kondo – spark joy. The 18 imaginative preschools built in Ahmedabad and Anantapur, incorporating the help of local artisans, are constructed with recycled materials, from broken tiles arrayed into wall and floor mosaics, to plastic bottle tops woven to form a graphic gate. Other locally sourced materials include compressed clay bricks, bamboo and screens that allow for cross-ventilation – one such metal-hewn screen is fitted into a concrete ceiling to lower the indoor temperature.

A collaborative effort between Australia-based volunteer architects – who work on-site for about six months – and NGOs including Manav Sadhna, the AWCs are funded by private donors and the coterie of architects themselves. Undergirding the efforts, TAP’s co-founder and president, Ms Jane Rothschild says, is a belief that good design should be accessible to all.

The former director of Architects without Frontiers and co-founder of Sydney-based practice Dickson Rothschild co-founded TAP with costumer designer Ms Jodie Fried in 2006. Since then, their ground-up initiative has grown into one that is driven by community engagement and uplifts disadvantaged groups typically shunted to society’s fringes – while garnering the attention of the Indian government.

DE51GN’s contributing editor Cara Yap speaks to Ms Rothschild to shed light on her design for good initiative.

You’re no stranger to humanitarian architecture. What informs your belief in the role of architecture in effecting social change?

We strongly believe that good design should be accessible to everyone, and not just the one-percenters. Though our anganwadis are small, they are built by applying design principles such as light, ventilation, beauty and joy, and have made a big impact on the community. Initially, we were focused on just building the schools, but progressively placed great importance on community consultation. From day one, our volunteers are observing in the schools, talking to the teachers, and getting to know the community, which is involved in every part of the design process. Volunteers make models of their designs and consult the teachers, kids and community leaders to ensure these are what they really want. It’s not about design in the typical architectural fashion, but ultimately, the community feeling a sense of ownership.

How did you come to learn about anganwadis and why focus on Ahmedabad to begin with?

I’ve always had a passion for India and met Jodie Fried at a talk at Sydney’s Powerhouse Museum. She had done a tiny renovation on one of the anganwadis in Ahmedabad, where she ran a homeware project. The local kids did designs for her from the anganwadis, which had few windows and were boiling hot inside, so that’s where it all started. We jumped on a plane together and did a second school, and things grew organically from there.

“We tend to work with lower caste communities that don’t get respect, and I think the fact that volunteers spend six months putting so much love into building something just for them makes them feel valued.” – Jane Rothschild, co-founder, The Anganwadi Project

What are some of the project’s challenges?

One challenge has been the language barrier between volunteers and local builders, but what’s really helped is our connection with architecture students and recent graduates from CEPT University, one of the best architecture schools in Ahmedebad. These volunteers – who understand local construction – are really important to us in terms of communicating with the community and builders, and interpreting the culture. With the builders, it’s been a lovely mutual learning relationship, so a lot of times the challenges become opportunities.

Was it initially difficult getting volunteer architects to commit a substantial amount of time to working overseas?

In the early days of our projects, it was more about renovating existing buildings, as the anganwadis are often run in houses rented by the government. It did not take us as long as constructing a new building, so our early volunteers were overseas for shorter periods. With that being said, our first volunteer ended up staying for two-and-a-half years, while another who was supposed to be there for six months stayed for 18. They really get passionate about and involved with the community, so it is not just about building the school and going home. We have now sent over 35 outstanding volunteers and they have gone on to do incredibly interesting work. One works for the Australian Red Cross as a habitat organiser in disaster-struck areas, while another is currently doing her PhD in urban design in public spaces.

How have the local communities contributed towards the design process?

We’ve used many interesting suggestions, such as having a temple embedded in the anganwadi, so that it will be well looked after, and using colours that relate to the particular area. Up north, the Neem is a sacred plant and we have incorporated it in every school. We’ve also used the community’s skills – there are amazing metalworkers who can weld anything and people who do beautiful mosaic work. We’ve hired traditional artisans from the Kutch region who do mudwork installations, while the kids help with the painting and gardening. I guess it has been more about community engagement.

“Our first volunteer ended up staying for two-and-a-half years, while another who was supposed to be there for six months stayed for 18. They really get passionate about and involved with the community, so it is not just about building the school and going home. We have now sent over 35 outstanding volunteers and they have gone on to do incredibly interesting work.” – Jane Rothschild, co-founder, The Anganwadi Project

How do the local materials fit into your model of functional yet aesthetically pleasing schools?

Our model of reduce, reuse and recycle is actually a very Indian philosophy – in fact, many of the students’ mothers in Ahmedabad are rag pickers. Material wise, we get free offcuts of broken tiles so these have formed an integral part of our designs. In one of the anganwadis, we noticed stains on the walls as young children with oil in their hair would rest their heads against them, so we developed wall mosaics out of practicality. In another school, the tiles were used to form circular floor designs to encourage kids to could gather around. Kutlos, which are traditional Indian woven beds, have been used as privacy screens and also hang from ceilings to reduce the heat load from metal roofs.

What are some of the requirements for building these schools?

Our volunteers need to abide by Australian building codes as closely as possible. We insist on engineer drawings for everything, and we try our best to follow the same processes we would adhere to in Australia.

What impact have the schools made on the local community?

Attendance has gone up and the project has empowered the community. For Harivillu 1, our first anganwadi in Anantapur, there was a quiet teacher who initially stayed in the background – the community leaders and builders did not even address her by name. Gradually, as she became really engaged with the project’s design, her personality changed. She became so powerful that by the end of the project, the builders sought her opinions. We tend to work with lower caste communities that don’t get respect, and I think the fact that volunteers spend six months putting so much love into building something just for them makes them feel valued.

What are your plans for the new project in Anantapur?

We work with Rural Development Trust and the anganwadis are owned by the government. What has been exciting is that government officials at the inauguration of Harivillu 1 were impressed and wanted our drawings to apply the same concept to other government anganwadis. We’ve also been contacted by a number of organisations around India and are now in the midst of documenting our community consultation process for them.

About the writer:

Cara Yap is a former travel editor who contributes pieces on thought leaders and social entrepreneurs to the likes of CNA Luxury and Singapore Magazine. She has a penchant for country roads that disappear into hills and end at the coast, plus cities with mouldering architecture. Yap is averse to minimalism; the curlicues and embellishments of the Art Nouveau style speak to her love of excess. When she is not covering in-depth human interest features and lifestyle pieces, she runs her backpacker’s hostel in Indonesia.

See the full image gallery here:

You might also like: