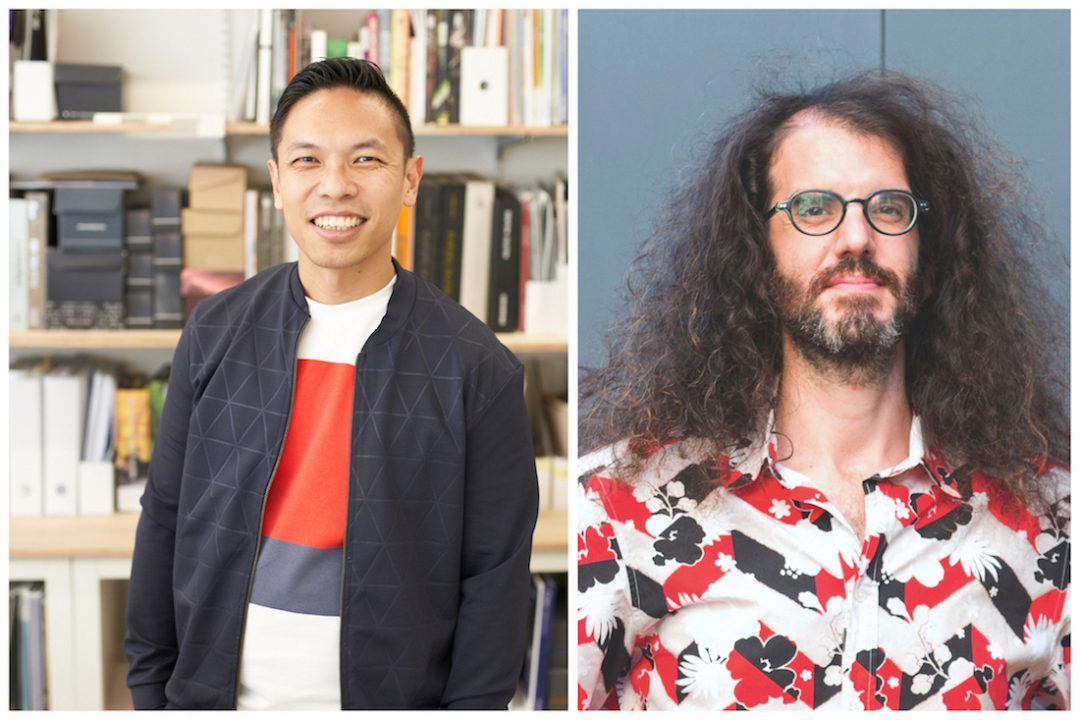

In an exclusive interview with DE51GN, WY-TO Group’s head of design, Yann Follain and architect Jonathan Poh discuss why adaptive reuse in Singapore is beginning to steer the conversation on sustainability in the right direction.

Back in 2020, Paris and Singapore-based practice WY-TO, led by head of design, Yann Follain (top right), and Provolk Architects of the WY-TO Group, helmed by architect Jonathan Poh (top left), joined forces to bring a community-centric design ethos underscored by sustainability. Among the first projects the new joint entity has bagged is the former Bukit Timah Fire Station, which is set to be transformed into a community node for nature, heritage and adventure enthusiasts.

As a key gateway to heritage and nature landmarks in the area, this historical site will soon feature an environmentally sustainable lifestyle hub that integrates urban farming, wellness, and nature-based activities, with generous community spaces amid lush greenery and rich heritage.

The project is the result of the ‘Reinventing Cities’ competition launched by the C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group and the Singapore Land Authority (SLA) in collaboration with Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA), National Parks Board (NParks) and Building and Construction Authority (BCA). The tender of this State property was awarded to Homestead Holland Pte Ltd.

‘Reinventing Cities’ is a global competition meant to serve as a model for cities around the world to implement carbon neutral and sustainable urban features within identified sites in cities across the world. The competition featured 25 sites in nine cities and the former Bukit Timah Fire Station (BTFS) was the first site in Asia to be included in the competition.

“This innovative competition is driven by the content rather than a developer taking a site, engaging an architect, and constructing a building and selling units,” explains Mr Follain, adding that this edition of the competition featured other cities such as Milan, Madrid, Capetown, Chicago, Montreal and Dubai, among others. “This competition is different because there are 10 challenges pertaining to climate change that need to be addressed. The mandate of the C40 as an organisation is to empower local communities by calling for innovative ideas. With cities now housing more than 50% of the world population, the sustainable strategies used in these [C40] projects then become case studies and even benchmarks for other projects.”

In a similar vein he points out that Reinventing Paris was initiated by Paris’ Mayor Anne Hidalgo five years ago.

The BTFS competition was launched three years ago and the second round took place just before Covid-19, with the ensuing impact of the pandemic turning the awarding of the project into a long process. “BTFS in a historical building that requires specific attention,” stresses Mr Follain, who moved from his native Paris to work in Southeast Asia several years ago.

Being a conservation site, any plans for the new development had to respect its history, provenance and context. Mr Poh notes that the conservation effort behind the fire station is intertwined with its connection to the adjacent green corridor and a collection of heritage buildings along the park connector network managed by the National Parks Board (NParks). “This fire station is going to be one of the nodes along the green corridor and gateway to Bukit Batok Nature Park,” he says. To dive deeper into the context of BTFS and determine its historical significance, Mr Poh and Mr Follain engaged Singapore-based conservation specialist Studio Lapis.

“We wanted Studio Lapis’ help with research into the significance of the building with respect to the overall planning starting from the origins when the fire station was a village community surrounded by farms,” shares Mr Poh. “That served as a good starting point for how we connected the history of the place to our concept – Good Food, Good Life.

Tracing the site’s history threw up some valuable points of interest that proved highly relevant to the new programming. Mr Poh continues: “It was a community of farmers, consisting mostly of the Teochews. Within the vicinity, there were smaller settlements inhabited by workers of the nearby factories and quarries. The research that Studio Lapis unearthed was interesting. We took cues from the research and built on the narrative of the fire station. We started to look at how some of the elements such as the gabled walls could be used to tell the story and the landscape could relate back to the original vegetation that grew over there. All of this harks back to the heritage of the project. There are many layers of information and research on the history of this place in our project. That’s how we see the integration of our idea with conservation.”

“The brief of the project was to protect the buildings, so none of them could be demolished. And importantly, no new building could be built.”

Yann Follain, head of design, WY-TO Group

One of the dominant themes in the project is the reference to a community created by volunteers. BTFS was also made and run by the volunteer corps before the institutionalisation of the Singapore Civil Defence Force. Referencing the same spirit, Mr Poh says that with the new project, the idea is “to create a new ground-up community that references the past through diverse programming, such as farms, F&B, and other community activities”.

With sustainability being one of the main facets of the C40 Reinventing Cities competition, the project required “inside the box thinking” – no demolition is permitted under the terms and conditions of the contest. “The brief of the project was to protect the buildings, so none of them could be demolished. And importantly, no new building could be built,” shares Mr Follain, while also expressing his disapproval of how conservation tokenism is practised by real estate developers. “In Singapore, usually if there is a historic building on the site, the developers will preserve it as a gateway or special feature while building a new condominium structure around it.”

“Sustainability is about preserving buildings in an adaptive reuse way – how you transform them to cater to the new needs of an inclusive society. A gated private community doesn’t entirely fulfil the definition of a sustainable building.”

Yann Follain, Head of Design, WY-TO Group

In the case of the BTFS, it’s not just the building that is part of the heritage, but the entire compound, and it was crucial to preserve it in its entirety. “We wanted to appreciate the building the way the former firemen who worked here would have appreciated it,” Mr Follain reflects. “When Studio Lapis was doing their research to understand how this site is placed in the greater context of Bukit Timah, it was related to the surrounding farms and forest. Those two narratives have been woven into the project – Good Food, Good Life – and also the connection to the Green Corridor which is the gateway to the nature reserves.”

For Mr Follain, sustainability and creativity are not mutually exclusive. “Sustainability is about preserving buildings in an adaptive reuse way – how you transform them to cater to the new needs of an inclusive society. A gated private community doesn’t entirely fulfil the definition of a sustainable building.”

CONSERVATION AND ADAPTIVE REUSE: THE GOLDEN MILE COMPLEX CASE STUDY

As a strong proponent of conservation and adaptive reuse, Mr Poh, who is involved in the Singapore chapter of Docomomo, an international non-profit organisation dedicated to the documentation and conservation of buildings, sites and neighbourhoods of the modern movement, was part of a citizen-led campaign to save another national icon – the Golden Mile Complex on Beach Road – that was purported to go for redevelopment. Citing the difference between the BTFS conservation project and Golden Mile Complex, Mr Poh posits that the latter is a private entity with multiple stakeholders, who are inclined to realise the maximum commercial potential of their asset. On the other hand, BTFS is part of an existing stock of buildings – many of which are not conserved – that SLA owns.

“For the owners of Golden Mile Complex, there was a small window to achieve the conservation status, whereas the SLA-owned buildings don’t have that urgency to sell. There is time to think what uses could be best suited to such buildings. It’s hard to draw parallels but as a practice, it’s fascinating to work with heritage consultants because of the brief on conservation. You are not introducing new carbon but utilising and preserving the embodied carbon in the existing structure. That’s the aligned part. In the case of the Golden Mile Complex, there was a renewed push because it has a lot of importance in Singapore’s built heritage, the urban ideas that it embodies, and because of the number of people behind it. But we have always followed this ethos in our practice,” says Mr Poh.

While the advancement of sustainability in Singapore is a work in progress, Mr Follain suggests that the precedence of Golden Mile Complex isn’t going to change the mindset overnight. He cites the example of yet another modernist building – Pearl Bank – which also happened to be a favourite and couldn’t be saved. “Perhaps, because of Pearl Bank, there was an added push to save Golden Mile Complex, but there are so many other buildings that don’t have the same recognition as Golden Mile Complex – protecting the building is not just about the heritage but also the environment and carbon footprint. There are multiple initiatives and some are more fruitful than others. But our wish that the private sector will conserve more buildings than build new ones is going to take some time be realised,” observes Mr Follain.

“In the case of the Golden Mile Complex, there was a renewed push because it has a lot of importance in Singapore’s built heritage, the urban ideas that it embodies, and because of the number of people behind it. But we have always followed this ethos in our practice.”

Architect Jonathan Poh, founder, Provolk Architects

Both Mr Follain and Poh agree that conservation is just one way of talking about the environment, and that adaptive reuse is gaining ground in the industry to counter over-demolition and try to embrace more sustainable construction. This approach is palpably visible in the BTFS as conservation comes on the back of a strong adaptive reuse plan that can be modern, reused somewhere else. Despite his inclination towards creating an inclusive and accessible community, Mr Follain doesn’t eschew the idea of commercial viability. He believes that mindful conservation and commerce can be happy bedfellows.

“Adaptive reuse should become something for the community and profitable for the businesses as well – similar plans could then be implemented for younger buildings that are still part of the larger heritage,” he suggests.

Yet another vital touchpoint in the larger conversation on sustainability is circularity and reuse of buildings and building materials and Mr Follain believes that things are moving in the right direction, even if slowly. “The Green Plan is focused on sustainable lifestyle and practices. We have not yet reached a stage where circularity becomes a priority – it’s not just about recycling plastic bottles,” he emphasises. “When we can say that 100% of waste materials from buildings are being reused, when we go beyond that, then we can point out what goes where and how it is being used. In this approach of circularity, it’s not just top down but also bottom up.”

INNOVATIONS IN THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT SECTOR IN SINGAPORE

In the past decade, the building and construction sector in Singapore has witnessed a transformation in terms of building regulations that are geared towards sustainability. Has it also led to new innovations in terms of the materials and techniques used? Mr Follain expresses scepticism about the scale of innovation and that there are multiple opportunities to break new grounds. “Sure there is widespread adoption of Prefabricated Prefinished Volumetric Construction (PPVC), but besides automation, it has not led to a radical innovation. We should push for Mass Engineered Timber, even in Housing and Development Board (HDB) flats. Why aren’t we constructing more waste to energy plants, for example?” he says.

However, he points out that there have been multiple innovations in the country’s infrastructure, such as reservoirs that have been designed specifically to address the water scarcity challenges. “The same level of innovation as seen in infrastructure should also be done in the built environment – we should not be content with just sky greenery and rooftop gardens. The construction achievements should go beyond building the tallest tower with PPVC. Circularity is important – trace our materials, their origin and journey,” responds Mr Follain.

Echoing his business partner’s sentiments, Mr Poh shares that several noteworthy innovations in the public sector infrastructure sector have also pushed architects to view buildings differently. A similar level of innovation is now providing the impetus in the built environment.

“In terms of energy, the Singapore Government is looking at floating solar farms, hydrogen energy to run power plants, and getting clean energy from overseas, such as solar energy from Australia,” he says.

“I think in terms of innovation, desalination plants like Keppel Marina and the Marina Barrage, have really started to marry infrastructure facility with public spaces. That, in my opinion, is an innovation that is led by the government and it is commendable. There are a lot of things that they are further exploring, especially in risk management, and protecting coastal ecosystems. They are also introducing new benchmarks for sustainable industrial practices. In the private sector though, the pace of innovation is much slower. As an SME, we are also pushing it on a different scale and it’s all aligned with the SG Green Plan 2030. The government is going at a high speed in the sustainability direction but SMEs like us are also going parallel to keep aligned with the government’s vision.”

Expounding on the fact that while architects can propose several innovative measures and features in their design and programming of the buildings, it often centres on what kind of stance the clients and stakeholders are willing to adopt. “It takes a lot of energy and education for small firms like us to convince clients to use innovative solutions because the mindset needs to evolve but things look promising and it’s moving in this direction,” says Mr Poh, adding that it is equally important that the middle tier of suppliers and service providers also play their part to create effective solutions that contribute to the conversation.

“I think in terms of innovation, desalination plants like Keppel Marina and the Marina Barrage, have really started to marry infrastructure facility with public spaces. That, in my opinion, is an innovation that is led by the government and it is commendable. There are a lot of things that they are further exploring, especially in risk management, and protecting coastal ecosystems. They are also introducing new benchmarks for sustainable industrial practices. In the private sector though, the pace of innovation is much slower.”

Jonathan Poh, Founder, Provolk Architects

Similarly, industry-led organisations such as the Singapore Chapters of Architects’ Declare and Construction Declares – a global petition uniting the construction and built environment industry are also helping to shift the mindset. “The action is not yet significant but it’s better than not having anything at all,” says Mr Follain. “Its value lies in raising awareness within the architecture community. If you’re a young architect and have questions on sustainability, you can reach out to the organisation. But it’s not like the UK where everything is debated, it’s a much smaller community here.”

It is noteworthy that the Singapore Institute of Architects also has its own initiatives – principles on sustainability that encourage practices to adopt them. “Sustainability has to become innate to the work that architects do and not just because they want to attain the green mark for the developers and allow them to gain additional plot ratio. It has to be sincere for the planet and not just for profits,” Mr Follain asserts.

EXEMPLARY BUILDINGS IN SINGAPORE

With a deep involvement in preserving the modernist built heritage of Singapore, both Mr Follain and Mr Poh have extensive knowledge and interest in the realm. They also have their favourites. “The Colonnade by Paul Rudolph is one of my favourites,” says Mr Poh of the 1980 condominium in Singapore’s upscale district 10, Orchard Road precinct.

“The Colonnade by Paul Rudolph is one of my favourites. The building set new standards for tropical living with the dual prefabrication and visual intricacy.”

Architect Jonathan Poh

“The building set new standards for tropical living with the dual prefabrication and visual intricacy. “I had always seen it in pictures but recently I had the chance to visit it briefly and as I entered, I was amazed at the amount of complex detailing and finesse that this building has. The units have split levels and each unit is unique on its own and the structural system that supports it is also quite complex. For it to be built at that time, it’s really commendable. And for obvious reasons, Golden Mile Complex is also a favourite for its uniqueness and significance.”

For Mr Follain, there are many that he finds impressive for what they are and what they have been trained to handle as a challenge. “One building in particular, Pearl Bank because when I first moved to Singapore, I lived there so I have strong emotional links to it. But when I was living there, I could see another icon being built that was the Pinnacle @Duxton,” he shares. The groundbreaking public housing project by ARC Studio Architecture + Urbanism, led by architect couple Khoo Peng Beng and Belinda Huang, has won global acclaim for its innovative urban living concept.

“I find it impressive for its scale, size, and what it was designed to convey – to become a new typology in affordable high-rise public housing in Singapore,” says Mr Follain. “Having gotten to know the architects over the years and collaborated with them, I appreciate how important this building is in terms of creating social connections and offering to the inhabitants the youth of the city that we rarely get the chance to. I find it generous in the way it articulates the different dimensions – the ground floor and the connections, the neighbouring historical neighbourhood of Chinatown. I find it a lot more glorious than the other commercial tall buildings in the CBD area. That again gives a glimpse into what the future of Singapore can be.”

Mr Follain is appreciative of yet another project that is not necessarily a building but a public space – the Bishan Park by Atelier Dreistel which is now Ramboll Studio Dreistel. “The level of innovation, what it tried to do and that became the norm for the other parks in Singapore, that’s something that was extremely challenging at that time. It broke all the regulations and pushed for new ideas, and most importantly, convinced people. And now when we see the Jurong Lake District, it’s the second generation of this project – which is very important for biodiversity, storm-water harvesting and sustainability.”

“The level of innovation, what it tried to do and that became the norm for the other parks in Singapore, that’s something that was extremely challenging at that time. It broke all the regulations and pushed for new ideas, and most importantly, convinced people.”

Yann Follain

THE ROAD AHEAD FOR WY-TO AND PROVOLK

While Mr Follain and Mr Poh are focused on the BTFS project, the joint entity, WY-TO Group (WY-TO and Provolk Architects) has several projects in the bag.

“We lost many competitions but at the same time, won others. Our ideas are always underpinned by the same ethos of conservation, sustainability and community. BTFS is a synthesis of all those ideas, and exploration,” says Mr Follain. “When people ask us questions like ‘what’s the design gesture?’ and ‘what’s the mark of the architect?’, there is no mark of the architect because it’s an existing building. It becomes apparent that there is a lack of understanding about what an architect brings that is beyond just designing an object, such as generating a programme, working with the local community and understanding the historical context. Jonathan has also been doing similar work with Docomomo and Singapore Heritage Society.”

By the virtue of its ingrained belief in creating inclusive communities, the joint practice undertakes many community-centric projects. “We just opened the children’s biennale, and in the works is a heritage gallery for St James Power Station,” says Mr Follain. “Jonathan and I are indirectly and directly involved in the concept masterplan and urban design for the future of Paya Lebar Airbase – it’s also a continuation of the BTFS project. We also participated in the old Changi General Hospital project competition, where we combined sustainability, heritage, conservation, narrative and storytelling. We are working on residential and material design projects.”

With an uptick in economic activities, cultural activities are also resuming and the practice has won the commission for a museum project in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

Summarising the practice’s deep-seated beliefs in sustainability and community, Mr Poh and Mr Follain are convinced that the three Ps – people, planet, prosperity – can successfully happen and it can show that in Singapore, community and environment form the bedrock of progress. “We are one of the countries that can be impacted by climate change with sea levels rising, water scarcity, and heat gain. Whatever we do should be geared towards combating climate change. There are alternatives to unsustainable and people-unfriendly buildings. These are geared towards connecting us with nature and environment in the post-Covid-19 era,” concludes Mr Follain.

You might also like: