Bangkok-based architecture practice Imaginary Objects was co-founded in 2018 by architects Yarinda Bunnag and Roberto Requejo Belette. Bangkok born and bred of mixed Swiss and Thai parentage, Ms Bunnag completed her architecture studies at Cornell and Harvard Universities, and thereafter returned to Bangkok. She now teaches at the International Program in Design and Architecture (INDA), Chulalongkorn University. She currently serves as the regional president of the Asia Designer Communication Platform.

Mr Belette, born in Spain, raised in America, and now based in Hong Kong, is an alumnus of the prestigious Cornell’s School of Architecture Art and Planning (AAP) and Columbia’s Graduate School of Architecture Planning and Preservation (GSAPP). Subsequently, he worked with Office for Metropolitan Architecture and Steven Holl Architects (SHA) in New York and Beijing. He has taught architecture at Cornell, NYIT, INDA, HKDI, and HKU.

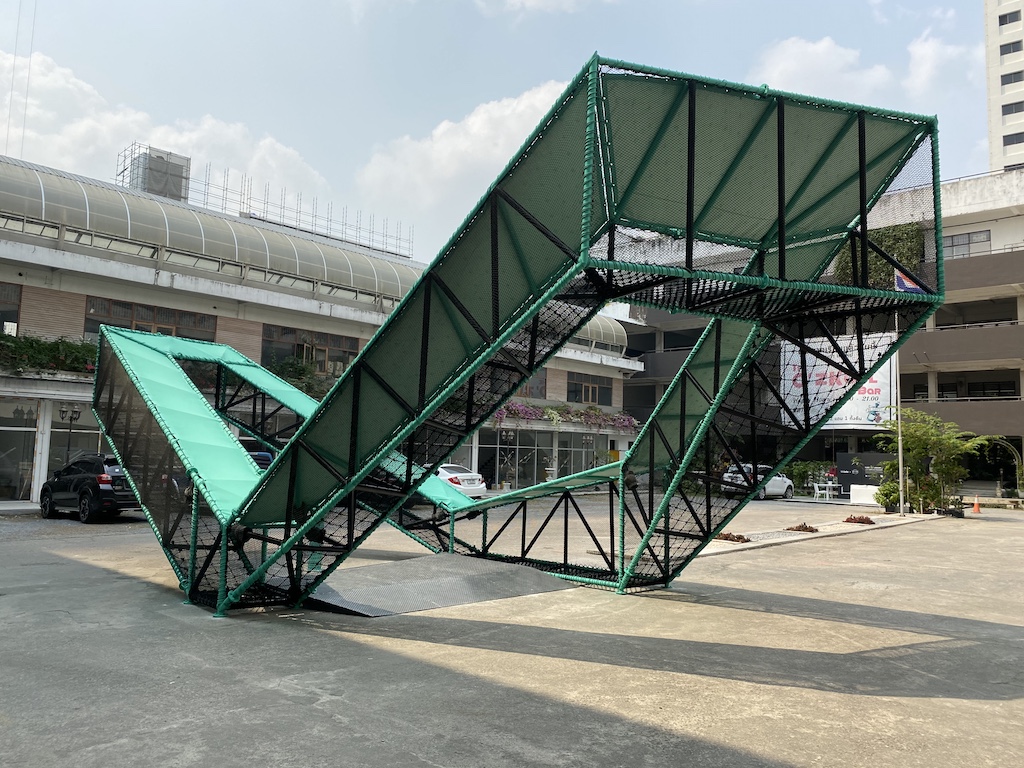

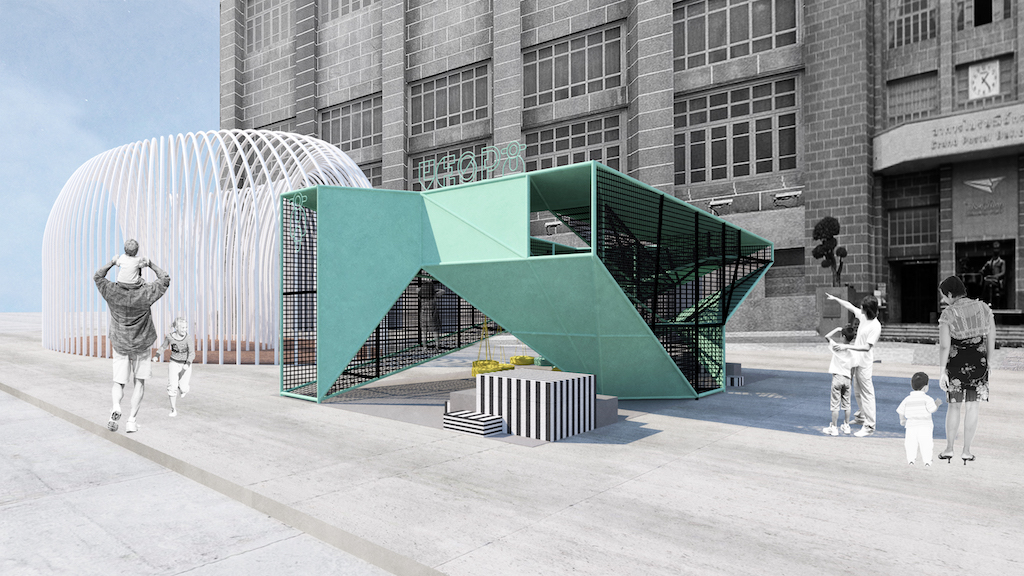

During Bangkok Design Week earlier this year, Imaginary Objects designed a public playground for children, a project supported by Vespa Thailand. The project aimed to highlight the importance of playgrounds in dense urban cities such as Bangkok, considering how few playgrounds are there in the Thai capital. DE51GN speaks to Ms Bunnag and Mr Belette to shed light on how a city’s vacant community spaces can be transformed into usable public amenities and the accompanying challenges.

How did the collaboration with Vespa and Bangkok Design Week come about?

Yarinda Bunnag: Our whole campaign was to increase the number of playgrounds in Bangkok because we have very few public spaces, let alone spaces for kids. We tried to promote that aspect during the Bangkok Design Week and around 10 people have already contacted us during the design week and also afterward wanting to sponsor a playground or commission one for their own developments.

We were designing another project for Vespa. It’s called the House of La Dolce Vita Scooter which is a pop-up museum. While we were designing it, we also created a playground for the owner Vespa Thailand, Pornada Tejapaibul, for her children in her backyard. As we worked on that project, we realised that we enjoy designing playgrounds very much in terms of scope and duration of the project, it’s immediately gratifying to see kids enjoying these structures.

Then we got into a conversation with this social enterprise, another design company. So we ended up expanding the idea of the playground for the city and not just a private client. We proposed this to Ms Tejapaibul that instead of building one of these for your children, what if we build a few for the other children in the city and she really liked the idea.

Why is there a lack of playgrounds in Bangkok?

Yarinda Bunnag: It’s a complex question to answer because it stems from the way that the city was initially designed. A lot of urban spaces belong to private developers and those that are not, belong to either the department of transportation, for example, spaces under the highway and the rest is for the low-income community. There is already a lack of space and a high density of vulnerable housing. So when there is empty space, people would rather make money off of it.

We approached a few low-income communities here and offered them a playground for free. All they had to do was give us some space. We got all sorts of responses. One community said that they would rather rent the space out for carpark so they actually make money by charging people who park their cars there rather than covert it into a playground.

There was an old Muslim community that we contacted that actually had space but it was an old cemetery and considered sacred space, and you probably don’t want children to be jumping up and down on that land. They would rather leave it as an abandoned plot. a lot of the feedback that we got from the various communities was surprising for us to find out and we are also learning from them.

There are lots of agendas, conflicts, and constraints that we didn’t know that are associated with these empty spaces. But otherwise, Bangkok is really lacking public spaces. Even private developers, when they, for example, build a shopping mall or a high-rise building, they develop a plaza in front of the building that is monitored by security guards to ensure that street vendors don’t trespass or people who are going to the building are not just there to use its facilities.

The idea of social contribution and consciousness isn’t a high priority in Bangkok, unfortunately.

“The fees for working on government projects are ridiculously low. Sometimes like 1.5%. This discourages a lot of architects from participating in public projects. For some reason, there is a consistent preference for Neo-Classical or Neo-vernacular for Thai architecture in public buildings. Even if you see the most anticipated project being constructed right now that is the new Thai parliament, the selection was done through a competition that attracted numerous practices, and the firm and design that were selected are very traditionally Thai.” – Yarinda Bunnag

Design has evolved in Thailand – from traditional to contemporary but with a focus on preserving traditional materials and techniques. Do you follow such an approach in your design?

Roberto Requejo Belette: Adjacent to our previous office was a warehouse where we designed an intervention designed for the owner of Vespa Thailand that wasn’t necessarily for Vespa the brand or products. We preserved the existing structure and introduced an independent object with a somewhat modern aesthetic and form. Ideally, this is also our intention with materials that they have some irregularity in them so that they are more approachable and more artisanal.

As it pertains to the playgrounds themselves, they are primarily steel pipes with netting and fabric. You wouldn’t immediately assume that those are traditional materials so in this case what we went for was expediency in terms of construction but also affordability. So even though the playgrounds were sponsored, it was important that they were quickly realised and economical. The playgrounds that we built for Bangkok Design Week represented traditional techniques.

Is design and architecture in Thailand driven mostly by the private sector?

Yarinda Bunnag: It’s unfortunate but it has to do with a few factors. There are a few young practices that are paving the way and have made us known internationally. Ironically, most of the projects that have won international recognition are all private. As for public projects, there are a lot of rules and regulations as to who can participate in the competition if there is a competition. Mostly, these tend to be by invitation competitions, and the firms that are usually invited are the ones that already have some connection with the government already.

The fees for working on government projects are ridiculously low. Sometimes like 1.5%. This discourages a lot of architects from participating in public projects. For some reason, there is a consistent preference for Neo-Classical or Neo-vernacular for Thai architecture in public buildings. Even if you see the most anticipated project being constructed right now that is the new Thai parliament, the selection was done through a competition that attracted numerous practices, and the firm and design that were selected are very Thai. So the project is rooted in a lot of Buddhist symbolism and Thai history. It’s clear that this kind of style is the preference for public institutions here. Because of all those factors, you don’t see many contemporary designs in public buildings.

“The playgrounds that we created for Bangkok Design Week, I can’t imagine how much longer they would have taken in places like New York and London because there are more regulations for safety, accessibility, materials, and fire code, among others. That’s not to say that our playgrounds here are not safe, but they had to be done very quickly. Lack of regulations still allows for more exciting designs.” – Roberto Requejo Belette

Having studied and taught at Ivy League universities in the US, you have chosen to return to Asia. What brought you here?

Roberto Requejo Belette: I moved to Beijing in 2007 for two years, and then I moved to Hong Kong and I’ve been here since. The initial reason for moving was for a better opportunity to design bigger, larger, and more expressive buildings than were being built anywhere else at the time. This was during the Beijing Olympics which has already been a long time ago. Things have already toned down a lot. Once you’re here, opportunities come up and gain a life of its own. I’ve never found a reason to leave Asia or even Hong Kong for that matter. I still see that there are greater opportunities for creating an impact. Things aren’t as predictable or formatted for the most part, so there are a lot of opportunities for experimentation. That was definitely the case in Beijing and I think Bangkok also has a long-established urban context like London and New York, and there is certainly a lot of flexibility.

The playgrounds that we created for Bangkok Design Week, I can’t imagine how much longer they would have taken in places like New York and London because there are more regulations for safety, accessibility, materials, and fire code, among others. That’s not to say that our playgrounds here are not safe, but they had to be done very quickly. Lack of regulations still allows for more exciting designs.

What are the biggest challenges you face as architects in one of the world’s most vibrant and densest cities?

Roberto Requejo Belette: An easy answer would be language, but I suppose more than language, it’s mostly culture but I’ve been here long enough to feel that I have adapted. Culturally, sometimes there are things that are not explicitly stated and that can be implied which can difficult to decipher initially. But you learn to adapt.

One thing I could add from my personal experience is that a lot of the clients or potential clients don’t yet value design as compared to clients in the West. The ability for us to charge the design fee. Maybe it’s a global thing, architects in Thailand actually get paid a lot less than many other professions. For us to be able to charge a good fee, we realise that it takes a good client who appreciates art and design. Otherwise, they would rather hire a contractor and show them a reference to recreate. A lot of times, clients here also equate the design fee to the construction cost so they think if they want something cheap, the design fee should be cheaper. It’s actually more challenging to design something cheap and do it well.

You are active as both practitioners and academicians. How do you balance both?

Roberto Requejo Belette: It depends on the timeline. Up until recently, I was exclusively practising working with a Dutch firm for eight years and occasionally finding the time to teach or conduct a workshop, and Nina was primarily teaching and the roles have been reversed now. Balance is sometimes circumstantial. When you get sick of doing one thing, you pray for the other. I find it very important to have one foot on one and the other in something else. It’s good for inspiration but practising is a reality check. It’s imagination versus pragmatism.

Who are your favourite architects?

Yarinda Bunnag: I like Peter Zumthor very much.

Roberto Requejo Belette: For me, it’s Lebbeus Woods

You might also like:

Shma Company architects designs sustainable air purifying installation for Bangkok Design Week