The built sector in India continues to grow, primarily driven by the private sector. DE51GN speaks to New Delhi-based architect Mr Utssav Gupta, partner and CEO of Creators Architects that is leading a new movement in the built sector not just through innovative and strategic design, but also through the lens of how architecture impacts an organisation’s business objectives in the short and long-term. An alumnus of the prestigious Architectural Association in London, and a second-generation architect who now leads the practice founded by his parents, the late Mr Rajiv Gupta and Mrs Mukta Gupta – both architects by training – Mr Gupta believes that the integration of strategic thinking and advanced technology can help to create mindful architecture that imbibes sustainability right through the conception, design and building stages, and not as an afterthought.

He details his research-oriented thought process in his book Rebound that focuses on the intertwined relationship between business and design, and its successful outcome. In this exclusive interview, Mr Gupta talks about the need to optimise every square inch of built projects to make them truly sustainable and how the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic has brought to fore the socio-economic challenges in India’s capital city that impact urban development.

Why is institutional architecture often neglected in India? There is a visible lack of museums and public institutions?

It’s mostly due to the policies and the lack of holistic thinking about the socio-economic structure and investment. For example, we recently worked on a project in Guwahati city in north-eastern India, where we worked together with government officials and bureaucrats to understand and assess the financial investment and how to gauge the return on investment. In India, the biggest challenge is the scale and diversity in demographics.

How would you describe the challenges and opportunities for architects in India?

More often than not, it’s the lack of an understanding of the correlation between the client’s own business objectives and the contents of the building. Clients only expect project visuals. If the building doesn’t have strong content that qualifies its programme, then the objective of the building is not met. Our approach is to work closely with the client to study their business plan and the subsequent output can be transformative with regard to the project. The strength of our projects is tied to our responsibility towards the context.

In most projects, we often begin with what we call an idea-centric gap. To fill this gap, we organise a mastermind session with the clients because we realised that dialogue is almost entirely missing at the initial development stage, and we want to initiate that. Unfortunately, academia in India doesn’t talk about the absence of this crucial aspect of any project commission.

What is the perception of sustainability in the built environment sector in India?

In India, sustainability is primarily being embraced by the private sector, but it’s not so prevalent in the public sector or institutional developments because there is no perceived financial incentive for them to do so. Whereas, for us, when we work on a project, we translate the benefits of sustainable practices into actual numbers where the clients can see the long-term financial and physical benefits of investing in sustainable aspects such as the materials used.

For instance, we convince our clients by making a case for a long-term business impact through the use of sustainable practices in all aspects including the building. We worked on an academic institution in Surat in the western state of Gujarat which also has a very harsh climate and strong monsoon. We applied passive design technology to design the air circulation such that it brings in the air but not water during heavy rains.

An institutional building by Creators Architects in the Indian city of Guwahati features a water body that transforms into a social and interactive space during summer season when the water evaporates.

We also emphasise strongly on optimising land usage as well as indoor air quality in our sustainability ethos. For example, we have been working on some concepts around water bodies that by nature are community-centric. But in India, what happens is that due to high temperatures and scarcity of water, these water bodies often evaporate. This prompted us to rethink such spaces and how we can help reinvigorate them. We proposed a fountain redevelopment for a public institution in India that houses such a water body. Our concept details how this space can be transformed into a social space if the water evaporates. When the water level drops, some new elements emerge which are initially submerged in water but when it’s exposed, it invites people to interact with the space and turn it into a collaborative space.

One of the projects by Creators Architects where the rooftop space of the project component was designed to accommodate a basketball court, effectively utilising space that would have otherwise been wasted.

Another aspect that I strongly feel that is missing in India is sports facilities. With more urban developments, open spaces are also becoming scarce and sports don’t get any priority. We have recently worked on three projects – a gated condominium two public institutions – that have sports areas embedded into them. These are essentially wasted real estate that would just be redundant. This required some detailed planning at the inception stage itself but once the sports area was integrated into the project, it found much favour among the residents as well as the community.

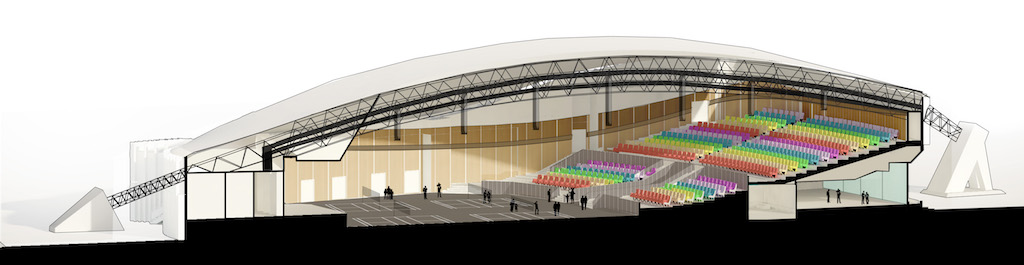

A lecture hall that can be used as an indoor badminton court to encourage multiple programming within a single project.

One of the projects among these was a hall for 3,500 people capacity that would be used a maximum of twice a year. So we told the client that why have a space that you can only use twice a year when you can make it function throughout the year. So the rest of the year, it is used as a badminton court since it’s already a covered space that required just a little more planning at the development stage. It started impacting the programme of the building as well. Of course, it utilises the space in an optimum manner but at the same time, as architects, we have to ask ourselves a vital question: are we going to use every inch of the space int he building we are designing because every inch equals carbon footprint. If it’s not used fully, then it’s a criminal waste.

Are there any major changes on the cards for urban planning in New Delhi?

Most of the Indian cities are mature, not unlike many in old countries. The urbanisation has already taken place here, even if haphazardly. There has been no real change in them for many decades. Unlike other big countries, say the US and China, we don’t create new cities once in a decade. I don’t see any shift in urban planning, maybe some incorporation of technology and smaller developments might take place to contain the ongoing pandemic and other such future occurrences. It’s virtually impossible for developing countries to bring about big urbanisation changes because it’s very capital intensive.

Is there a lot of migration from rural areas to cities still taking place in India and how does it impact the existing infrastructure in these cities?

Yes, there is still a lot of migration from rural areas to cities, especially among the lower strata of society. Back in the mid-2000s, there was a huge influx of migrants from rural areas who lived in make-shift accommodations under the flyovers, and on the streets. These migrants are generally daily-wagers who work in the construction or other labour-intensive sectors. As the decade got over, between 2010 to 2015, I saw a lot of improvements in the urban areas where you’d see fewer homeless people, at least in the core areas of the city; although they might still be present in large numbers on the periphery.

They got settled in proper accommodation and the living conditions improved. It depends on the area. The change was more noticeable in New Delhi than, say, a city like Mumbai. But now with the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic, there has been a lot of disruption to the lives of the daily-wage worker and street vendors who sell fruits and vegetables. In a commercial complex like where our offices are located, there used to be street food hawkers who are not there anymore. They might have gone back to their villages. With this workforce unavailable, urban projects will be affected as well.

What is going to make the city more liveable with so many changes happening due to the pandemic?

If you talk about infrastructure, the low-income group of people would travel by buses and it would be more point-to-point travel. That has now decreased. But it has not impacted the liveability of the city as it was not the major contributing factor towards the city’s inability to absorb people, to begin with. We can’t really say that this migration was the root cause of the city’s problems. The city grew because of the migrants, they were a part of the city and their job was a part of the city. With them gone, we can’t say that the city has become better; the other problems still exist such as congestion, density, and poor back pockets of infrastructure where real intervention is required. If anything, this Covid-19 pandemic has revealed, it is that our current standard of safety and viability needs to be improved.

Notably, most of the Covid-19 cases in India are occurring among the middle-income and higher-income groups and not the low-income section of society.

The World Mindfulness Centre is a spiritual and meditation facility in the southern Indian province of Telangana.

Please share details of your recent project – the World Heartfulness Centre?

It is a meditation centre in Hyderabad. The main meditation hall sits at the centre where the group mediation events are conducted for up to 50,000 to 75,000 people four times a year. Some of the main considerations were that the climate in this location typically has four seasons. Handling 50,000 people – that includes elderly and people in wheelchairs – in a hot climate who have to take off their footwear before entering. The materials and orientation had to take into account all these factors.

We look at each project through the lens of innovation. Apart from the four days of the main event, the main hall couldn’t be used as one large space for the rest of the year. We approached it from the perspective of diversity to make the space more versatile – a spatial strategy where the main hall could be divided into several halls, and even the open spaces between these different halls could function independently. The design is such that the building can function in its entirety or as several modules depending on the specific need of the events and meet-ups.

The World Heartfulness Centre is a non-air-conditioned space that has been designed using passive cooling strategies to cope with the hot climate of the region.

Circulation was another special consideration for this project because, with 50,000 people attending the annual event (when they do eventually resume), the carbon build-up can be quick. The cross-air ventilation had to be designed in a way that there would be a sense of freshness, especially during summer when the sun is high in Hyderabad and the city experiences extreme heat.

Circulation was another special consideration for the World Heartfulness Centre project because with 50,000 people attending the annual event (when they do eventually resume), the carbon build-up can be quick.

We conducted a thorough solar study in and around the site that helped us arrive at the most optimum orientation to prevent excessive heat gain. To this effect, the geometry of the building also helped. Additionally, we used high solar reflective index material on top to prevent the absorption of heat. It took two years of intensive research to arrive at the final scheme.

What were the challenges that you faced while working on this project?

Its location was one of the biggest constraints – it’s located 60km from Hyderabad and there was 20km of an unpaved, narrow road leading up to the site, which made the material movement and logistics quite challenging.

The top roofing is a steel structure in Polyvinylidene Fluoride (PVDF) – a type of glass membrane that was supplied by a specialist French supplier of highly innovative composite materials.

The site itself is located on cascading hills that face up to 180km/hour headwind. The structure had to withstand the wind load. The top roofing is a steel structure in Polyvinylidene Fluoride (PVDF) – a type of glass membrane that was supplied by a specialist French supplier of highly innovative composite materials that are suited for a diverse range of structural applications. The materials used on the lower floor and planters were produced locally.

Photos: Creators Architects

You might also like:

Studio Symbiosis Architects propose giant urban air purifiers to tackle pollution problem in Delhi