Dr Alessandro Melis, architect, academic and curator of the Italian Pavilion at the ongoing Venice Biennale’s International Architecture Exhibition has had a busy schedule. Not long after this interview earlier this month, he is leaving for New York where he is to join the New York Institute of Technology, leaving his academic position at the University of Portsmouth behind. In an exclusive interview with DE51GN, Dr Melis doesn’t appear to be fazed by the criticism of this year’s biennale pavilions which some critics have described a more representative of an art exhibition than real solutions facing urban cities and built environment.

While he admits to not having had the time to visit all the pavilions, Dr Melis is more optimistic than the critics. “It’s my first time as curator and as a curator, you tend to get busy with other programmes such as interviews with journalists,” he says.

The theme at the Italian Pavilion centres on Resilient Communities. It is a topic that ties in well with the overarching theme – How will we live together? – of the international architecture exhibition at the biennale, curated by Hashim Sarkis. Dr Melis clarifies that even though it might seem like it was solely in response to the theme, the fact is that his team had been working on the showcase even before the pandemic struck. Describing it as a sort of provocation, Dr Melis opines that even though resilience has become somewhat of a buzzword, it has a new perspective when viewed from a research standpoint.

The Italian Pavilion – comments Dr Melis – will itself be a resilient community, consisting of 14 “sub-communities” understood as operating workshops, research centres or case studies in accordance with two essential lines: a reflection on the state of the art in the matter of urban resilience in Italy and the world through the showing of works by eminent Italian architects, and a focus on methodologies, innovation, and research with interdisciplinary experiments straddling the ground between architecture, botany, agronomy, biology, art, and medicine.

“We also wanted to engage the stakeholders,” he says. “It’s more like a research lab where we explore relationships between architecture, ecosystems, and the city in the long term. Community is an important aspect. Hashim’s (Sarkis) question “how will we live together?” is quite meaningful. Mostly, as architects, we focus on theoretical framework and structure. How will the future city function and the community live in a cohesive social structure and be happy – these are the experiments we are focusing on. It was a good idea to move away from the macro-system of architectural planning to a minimum unit of social cohesion.”

In a somewhat prescient move, the project started out by focusing on climate change. Addressing two of the main consequences of the climate change crisis – health and social pressure, Dr Melis’ team started out by citing examples of Ebola, dengue fever, and establishing a connection between climate change and an increase in such challenges.

The pandemic corroborated our perspective. I wouldn’t say that we’ve been particularly clever or intuitive. It’s 20 years that the pressure has been building up and that this urban pressure is the cause of spillover diseases due to climate change. The coincidence of this [pandemic] happening at this time didn’t shock people in the industry.”

Dr Alessandro Melis, Curator, Italian Pavilion, Venice Architecture Biennale

“We have to look at them as symptoms, not causes,” he explains. “In a way, we were termed alarmistic at the time and now we are being seen as jinxing it. I said ‘we can’t be both, you have to decide one.’ However, the point is that the pandemic corroborated our perspective. I wouldn’t say that we’ve been particularly clever or intuitive. It’s 20 years that the pressure has been building up and that this urban pressure is the cause of spillover diseases due to climate change. The coincidence of this [pandemic] happening at this time didn’t shock people in the industry.”

Expounding the research-based laboratory approach, Dr Melis adds that he is interested in discussing the taxonomy of architecture and moving the role of architects from chief builder to that of a creator of ideas. “In all this investigation and looking for answers, the idea was never to create cities where we can have better social distancing or more hospitals,” he clarifies.

“Architects have to be more strategic and move in a systemic fashion. The pandemic has changed how we think but it can’t be solved by just building more hospitals and creating more space for social distancing. We have to take a step back and think like strategists. In Italy, we are advocating for less sight of construction and more fluid dynamic in urban architecture.”

UNEXPECTED DISCOVERIES

Along the way, Dr Melis and his team made many discoveries which he ascribes as one of the objectives in their research lab. “When we move back to the strategic role we need to move back in deep time and perspective,” he says. “In doing so, we learnt that the biology of evolution or casualty is not chance, rather creative serendipity. So we embraced the complexity because of which we were faced with many new discoveries which were not planned. We want to use this lab and monitor it and see what happens. We paid attention to the non-deterministic process of evolution as a possibility to embrace them for the future of cities.”

“The pandemic has changed how we think but it can’t be solved by just building more hospitals and creating more space for social distancing. We have to take a step back and think like strategists. In Italy, we are advocating for less sight of construction and more fluid dynamic in urban architecture.”

Dr Alessandro Melis

One example of this non-deterministic process as a result of biology of evolution could be seen in the exploration of the possibility of using slime mould in the facade of the buildings. Working with it, the team realised that they could align the growth of the organism according to the climate condition – specifically, expansion and contraction.

“At the end of it, we figured out that it’s like a living sunscreen system. Instead of using energy, you feed it oats,” shares Dr Melis. “We put a structure to host this thing. It’s called genoma and we put a biosphere inside it. The Italian building regulations are a lot tougher than, say, the UK. So it necessitated that we follow the rules, and design this structure as an installation that could test the concept for 300sq km. From an installation, it transformed into a building. It required more money and technology to build and went out of control. In the end, it wasn’t an installation anymore, it became a real structure that could be tested. Everything we are monitoring on this structure is like a building. We were able to gather a lot of data.”

And in a first-of-its-kind move, the Italian Pavilion at the Biennale Architettura 2021 will be carbon neutral. To achieve this goal, removal and integration of the materials of the 2019 Italian Pavilion for the 58th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia has been arranged, in addition to the permanent relocation of everything that will be produced. This will present a unique opportunity not only to exhibit works consistent with the proposal’s objectives but also an occasion to study the life cycle of development in a setting of resilience.

MINING THE DATA FOR CITIES OF THE FUTURE

Emphasising that the dissemination of data is even more important than the research itself, Dr Melis scheduled meetings with municipalities and the government of Italy and other civic authorities. “We now have a programme to establish a series of guidelines and charter,” he shares proudly, adding that a collaboration with an Italian TV show is also on the cards that will highlight the facets of this valuable research. “The Italian Charter for Resilient Communities – a humble attempt to interpret the United Nation’s 17 SDGs.”

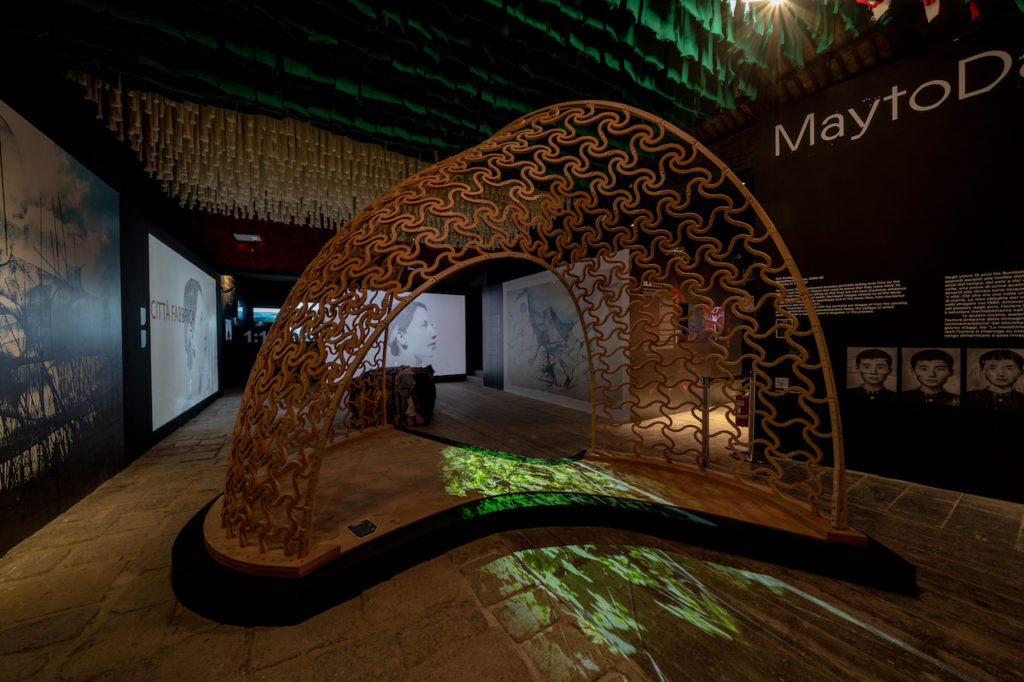

THE CURIOUS CASE OF ZAHA HADID ARCHITECTS’ INSTALLATION

Upon probing Dr Melis further about the somewhat incongruent presence of a Zaha Hadid project – a sinewy pop-up library called Alis – it comes across as an inorganic fit. However, Dr Melis defends its presence, describing it as a critical element. “It’s a little bit different from the rest of the elements in the pavilion but at the same time, it references our approach – it delves into the possibility of extending the taxonomy of architecture. It is symbolic of the post-pandemic liberation of culture.” He then segues into the sociological aspects of the pavilion.

“The Italian pavilion says there’s no ecological architecture without a just society,” he stresses. “We’re not trying to make a moral or ethical statement. We are analysing the biology of evolution. At the Italian pavilion, we represent what is important in terms of ecology and justice – this is my question pertaining to the provocation we are hoping to explore. When we talk about Zaha Hadid, who is the most important representative of contemporary architecture from a female perspective, the way we describe her at times is as if she was a self-indulgent crazy person. I’m not arguing against it or in favour of it, but I do want to add that this is a homage to Zaha Hadid. In the biology of evolution, there is an approach to the redundancy of shape which is very interesting. There is also a bias in architecture. Why do we have so many white 50-60-year-old Western men telling how bad Zaha Hadid’s architecture is? Why can’t she be perceived as an expression of the relevance of females in architecture?”

“There is also a bias in architecture. Why do we have so many white 50-60-year-old Western men telling how bad Zaha Hadid’s architecture is? Why can’t she be perceived as an expression of the relevance of females in architecture?”

Dr Alessandro Melis

CONCRETE SOLUTIONS FOR BETTER LIFE

Question him about the scathing criticism that the international pavilions have received about the exhibition being more art-centric than providing any real solutions, and Dr Melis quickly points out that his team has sought to find new ways to build ecological architecture. “The criticism of the Venice Biennale’s architecture exhibition hinges on not having the ability to recognise the physical form of architecture and defining it as a generic style of art,” he takes cognisance.

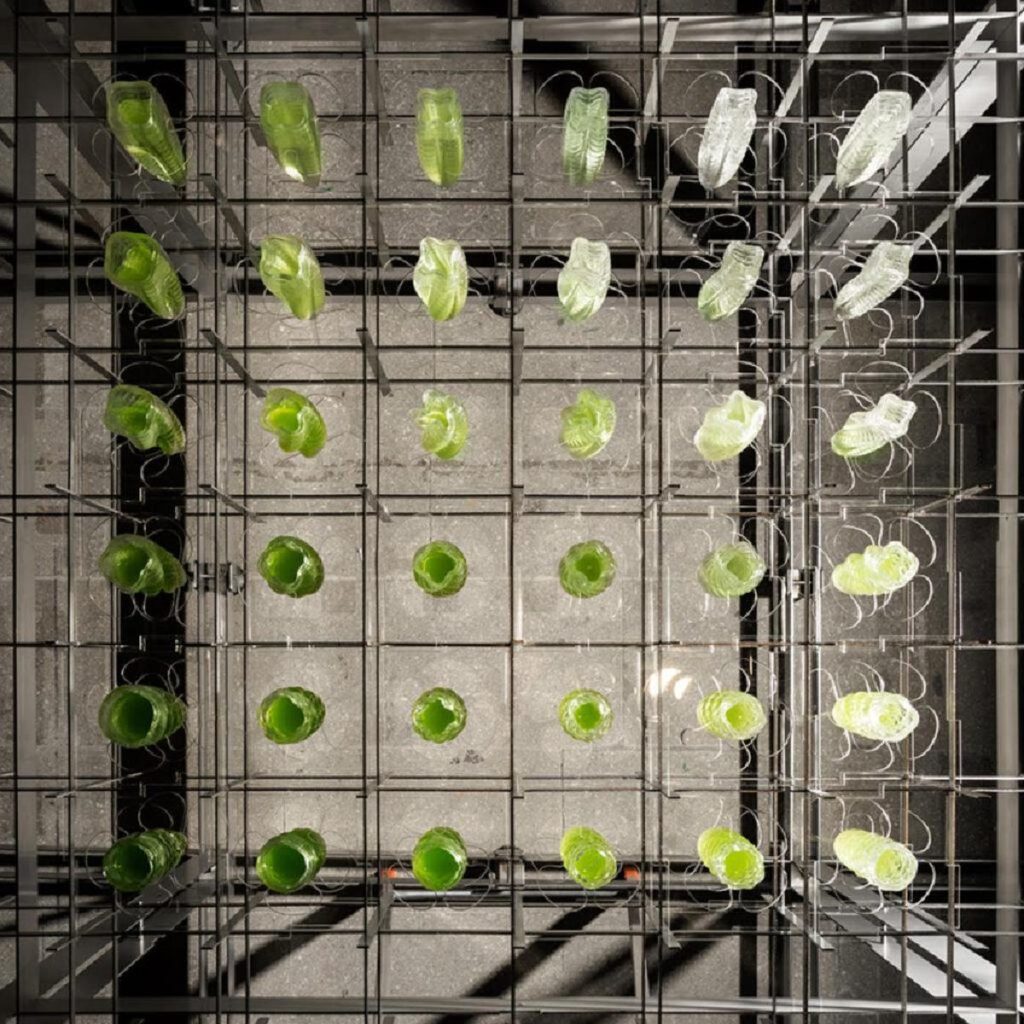

“The project of Ecologie Studio – part of the Italian Pavilion – for example, is a clear example of how we can achieve a symbiosis between nature and architecture,” he says, citing a specific example.

Dr Melis shares that he came across many interesting projects in the international exhibition in Arsenale. “For example, the idea of education in the South Korean pavilion, that is a relevant point,” he says. ” The local Venezia pavilion curated by Michele De Lucchi also stood out for its ability to create a coherent narrative; visually, the American pavilion with its timber structure was also quite interesting. Although in such an intimate approach, it’s hard to find the link between the installation and the ongoing crisis. The Spanish pavilion is quite stunning visually. They have deconstructed it and it’s the opposite of the Italian pavilion. We embraced the disorder, but also found some of the answers we were looking for.”

You might also like:

11 Asian and Middle Eastern pavilions at the Venice Biennale 2021