Few people know about the existence of farming villages in the heart of India’s capital New Delhi – home to almost 20 million people. Most of these rural areas have been consigned to oblivion and their people forgotten. Even as the city continues to modernise its public infrastructure – metro rail system, multi-lane highways, and swanky buildings – these urban-rural areas sited along the floodplains of the city’s Yamuna river are in stark contrast to the rest of the city – existing off-grid and fairly inaccessible.

It’s to help the residents of these marginalised farming communities that the city-based architect and founder of Social Design Collaborative, Swati Janu, galvanised a team of volunteers who came together to design a local school for the farmers’ children, who would otherwise have no access to education. The project won the coveted Beazley Award for Architecture 2020, conferred by the London-based Design Museum. This is the second consecutive year that the recognition has gone to an India-based project – in 2019 it was awarded to Mumbai-based Sameep Padora Architects for a school library project.

“Few people, if any, have a connection to the Yamuna river in Delhi because it’s mostly treated as a sewage drain; it’s teeming with pollutants and industrial effluents that are released into the river,” says Ms Janu over a video interview. “The river is like the city’s unattended backyard that no one faces. It’s only the farmers and fisherfolk who have an organic relationship with the Yamuna.”

Explaining the complex dynamics of the agricultural land propriety, Ms Janu shares that the farmlands are actually owned by the government that, for years, have been leased out to farmers on a short-term basis. Some of these “landlord” farmers, in turn, sub-lease parcels of land to tenant farmers who end up being at the bottom of the proverbial chain that leaves them without any sense of empowerment. Back in 2016, when the Delhi Development Authority demolished the school that served the farming community, the lessee farmers’ children were left with no access to any form of education. A legal petition was filed with the court on behalf of the community to arrive at a solution by Abdul Shakeel, a social worker who works closely with Ms Janu, and who was instrumental in getting her involved in the project.

Following the judicial process, it was determined that a school was required but that it had to be temporary. “The condition for the [school] to be a ‘temporary’ premise left a lot of things open to interpretation,” shares Ms Janu when asked about the guiding principles of the project. “It wasn’t supposed to be mobile, rather it was designed to be rebuilt. In case there was yet another eviction, it should allow the community to dismantle in a matter of a few hours, and store important parts of the school.”

“The condition for the [school] to be a ‘temporary’ premise left a lot of things open to interpretation. It wasn’t supposed to be mobile, rather it was designed to be rebuilt. In case there was yet another eviction, it should allow the community to dismantle in a matter of a few hours, and store important parts of the school.”

Swati Janu

Working on the project which is called ModSkool (short for modular school), Ms Janu says, has not only been meaningful but also a learning experience. “We really learnt from the way people in this community were already building their houses,” she says. “Their housing is built in a temporary way and that’s not just because of the eviction but also because they live on the floodplains, and the idea is to live very lightly.”

At the same time, Ms Janu and her team were also pondering on how to scale it up in the future and how could this model be recreated in many other places. Formerly known as Van Phool School (Wildflower in Hindi), it was originally established back in 1993. The original school no longer sits at the original site as some of the teachers, led by community leader Naresh Pal, have started another temporary school under a flyover. It was started during the pandemic with the help of community volunteers, while the school along the floodplains was being built.

“We really learnt from the way people in this community were already building their houses. Their housing is built in a temporary way and that’s not just because of the eviction but also because they live on the floodplains, and the idea is to live very lightly.”

Swati Janu

In 2018, the landlord farmer decided to discontinue the lease and take back the land, ModSkool had to be relocated further south of the river, which falls in Greater Noida, a satellite township east of Delhi. There, an NGO called the Child Trust, which runs a school called the Samagara Shiksha Kendra (holistic and sustainable education centre,) adopted ModSkool and helped in rebuilding it by recreating a holistic environment.

“The design we had visualised featured a sort of a permanent frame,” explains Ms Janu. “We have used mild steel sections that are just bolted together and that can be unbolted quickly.” The infill is made with locally available materials such as bamboo. Inspired by the local charpoy – bedstead made of light interwoven rope – weaving tradition, the team improvised it for the school. “We observed people building charpoy and we thought it could be featured as a local craft that is part of their tradition and visually, too, it’s appealing. Beauty plays a powerful role, and people take a lot of pride and ownership in something that is beautiful, in addition to the fact that it gets a lot of recognition.”

The temporary solution emphasised the role of local materials – that are both durable and adaptable – in the building process. A temporary solution such as the ModSkool proved to be a lifeline for underserved communities in such a remote rural area as the site is further inland, and could be located up to 1km inside from the edge of the main road. Ms Janu explains why such a school is a boon for the children and their parents. “The kids who attend ModSkool are very young and they can’t walk to the government schools that are a few kilometres away. Their parents are busy on the farms and they don’t have the time to drop the children to school every day. In the absence of any mode of transport, the children are at least able to attend some sort of an informal neighbourhood school. For this reason, they are also called bridge schools. ModSkool currently accommodates around 100 students and being an informal school, the grades are mixed.

Far from being smooth sailing, the project was riddled with several constraints and challenges. First of all, as a reflection of the precarity that surrounds the farming community, the school had to be temporary, and it had to be designed and built in a way that would keep any objections at bay. Keeping it low-key and working with a team of volunteers, helped in deflecting any potential scrutiny. However, the possibility of the project inviting unwanted attention was ever-present. “We would always discuss the possible scenarios and solutions in terms of the materials to be used,” Ms Janu recalls.

Other challenges were related to the lack of basic infrastructure amenities such as power and water supply and sanitation. “These farmers live off-grid and they have no access to electricity, no running water supply – just a hand pump – and no sewage system,” says Ms Janu. “We built the entire school with our hands, with the help of the local children and their parents – whoever had time contributed – and a lot of volunteers such as architecture school students also chipped in.” However, no power supply meant that crucial building processes such as welding and the power tools required for carpentry couldn’t be employed. This resulted in a longer construction period. When the team did finally arrange for a diesel power generator that was brought in on a tractor, it would break down frequently, interrupting the power supply. Last but not least, the building of the school took place during the peak sweltering summer season in Delhi which is nothing if not punishing.

Ms Janu and her team remained unperturbed by the myriad of challenges they faced in what seemed like a Herculean task. “We organised fundraising campaigns for the project and there was a lot of awareness created through social media. We received so much help from people. In the end, the project helped build all of us, and we went through life-transforming experiences,” shares Ms Janu proudly, adding that in particular, her colleague Nidhi Sohane and community leaders Mr Shakeel and Mr Pal helped bring the project to life.

“Most of the volunteers on the project were young people. To be a part of something like this is a very collective sort of building experience – just to see a part of Delhi which most upwardly mobile people don’t get to see. It’s a village in the middle of the city that most people have no clue about. Being designers and architects, we are so used to being on our drafting boards or computers that we don’t really do any hands-on work. We go to sites and talk to contractors but no one really talks to the labourers and no one uses their hands to do things. To be a part of something where you are building something with your hands and on the field, was a new experience for a lot of young designers and architecture students who had joined us. Everyone has their own reason and I have personally grown a lot.”

Having won much international recognition, ModSkool on the floodplains is undergoing some renovation work now to maintain its upkeep, and to deal with yet another challenge that is par for the course in the floodplains – snakes. “We are trying to snake-proof the school with the help of a carpenter. The school has an open concept for easy maintenance. But we are sealing some of the gaps to prevent snakes from coming inside. Instead of bamboo, we are using water-resistant construction plywood.

“It’s a village in the middle of the city that most people have no clue about. Being designers and architects, we are so used to being on our drafting boards or computers that we don’t really do any hands-on work. We go to sites and talk to contractors but no one really talks to the labourers and no one uses their hands to do things. To be a part of something where you are building something with your hands and on the field, was a new experience for a lot of young designers and architecture students who had joined us.”

Swati Janu

This, however, wasn’t Ms Janu’s first tryst with community-driven projects. Prior to branching out with her own practice, she worked with another Delhi-based social enterprise called mHS City Lab, a think-tank and implementing organisation that works towards improving the quality of informally built urban housing in developing countries.

Ms Janu opines that while there are a lot of designers and architects who work for people who have access to designers because they have the financial wherewithal, the objective of Social Design Collaborative is to work with and for the underserved groups in the city who don’t have this kind of access to design and architecture. “Most of our work is in urban areas. There is a lot of inequality in our cities – there are many groups that are underrepresented or left out in the planning process. Apart from farmers, we work with street vendors, home-based workers, recently, we are also trying to understand the issues faced by waste pickers, who are the informal recyclers of our city, and of course, construction workers.”

Pointing to the hardships these informal workers faced during the tough lockdown period last year, Ms Janu says there was a mass exodus of these workers from the city to their rural hometowns. “It was the first time it became visible that the informal workers in our cities had always been there but hardly noticed.”

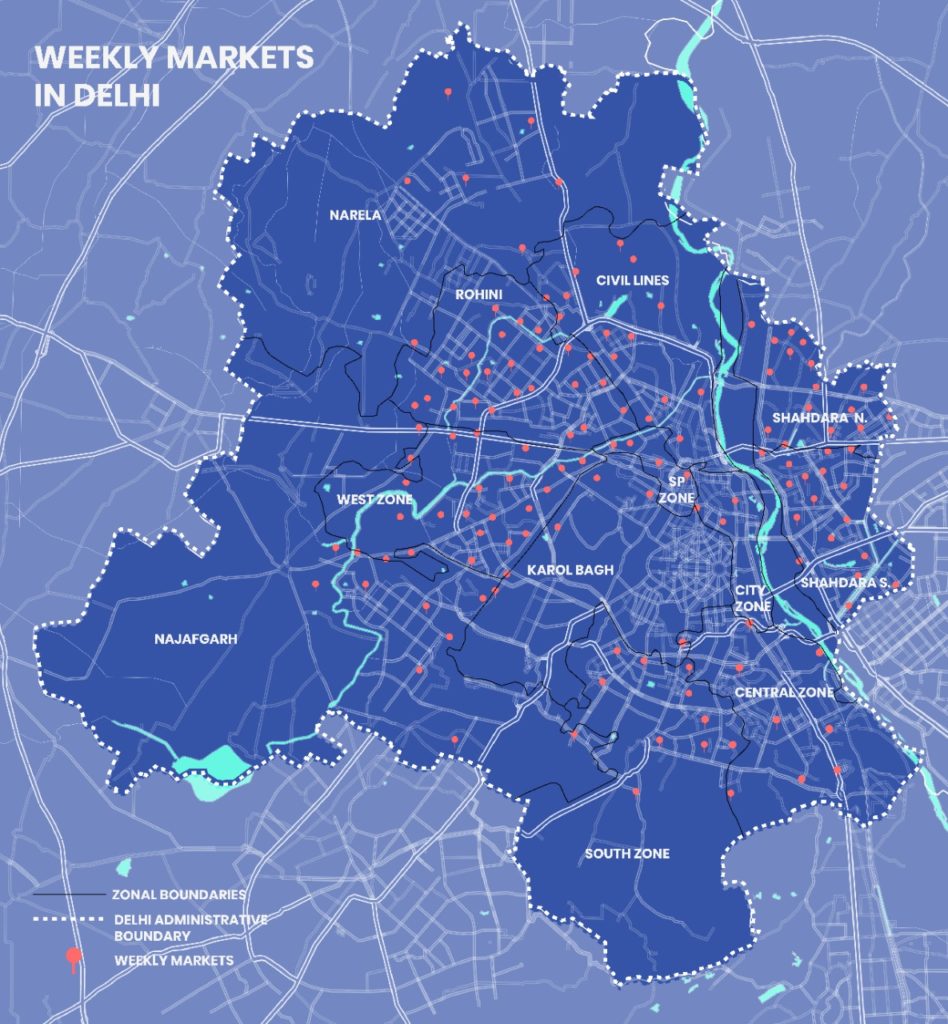

During the pandemic, Ms Janu and her team have been working with street vendors and helping them self-organise their weekly markets. She shares that like most old cities around the world, Delhi, too, is home to more than 500 such markets (see map above), of which 272 are officially recognised but there are another 250 informal markets that are not even recognised by the government yet.

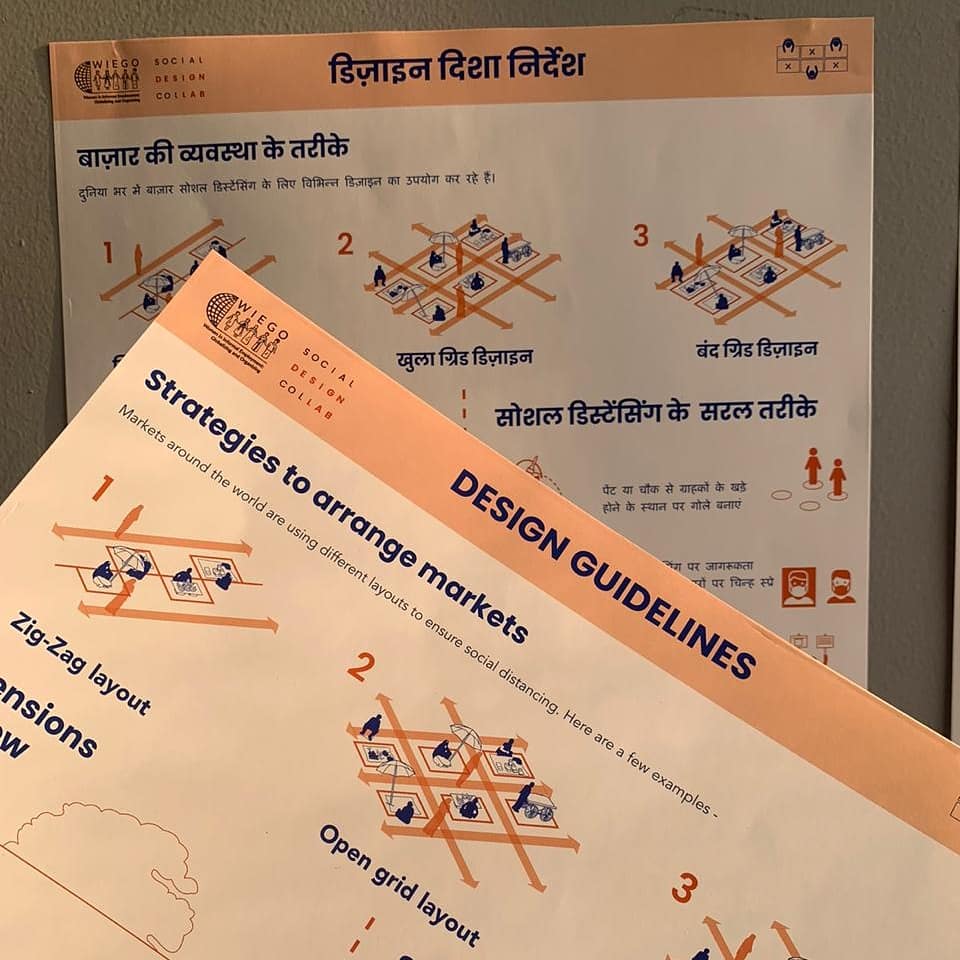

“How can we ensure that they get visibility, recognition and representation?” asks Ms Janu, questioning the socio-economic problem. “There has been an ongoing emphasis on social distancing around the world in public spaces and restaurants, but it’s also important to think about people like street vendors who can’t work from home and whose livelihood comes from public spaces. So we came up with simple public strategies on how to arrange these markets while ensuring safe distancing. During the lockdown, these markets were shut, and through advocacy, we tried to convince the authorities that these markets can be reopened and we will make sure that safe measures are followed. We came up with design strategies (above and below) and collaborations with other community-centred organisations.”

Such niche initiatives are part of the larger narrative that is integral to the ongoing formulation of Delhi’s 2041 masterplan. As part of its ground engagement initiatives, the government is trying to involve the general public through online consultations. “To give a voice to the underrepresented communities, we are working as part of this campaign called Mainbhidilli – a ground-up campaign to make planning in Delhi more representative and inclusive by engaging citizens in the master planning process,” shares Ms Janu. “It is our aim to start a public discussion on what kind of city the people of Delhi want and how to make it more equitable, just, and sustainable. Around 40 organisations are part of this initiative and have been been working closely with different marginalised communities through workshops and consultations. We want to create awareness about the masterplan, to ask questions like what does it mean to them and how they could engage with it. The Delhi Development Authority is trying to work on a similar model by working with the National Institute of Urban Affairs.”

“The idea of a singular heroic male figure who is going to save the day is a myth. A lot of architects fashion themselves around this idea, something that anyone who has read Ayn Rand’s Fountainhead will be familiar with. I don’t subscribe to that notion of design and architecture. Gender is a social construct and because women have had to adjust and adapt to many situations within these constructs, they have become good at people-centric work.”

Swati Janu

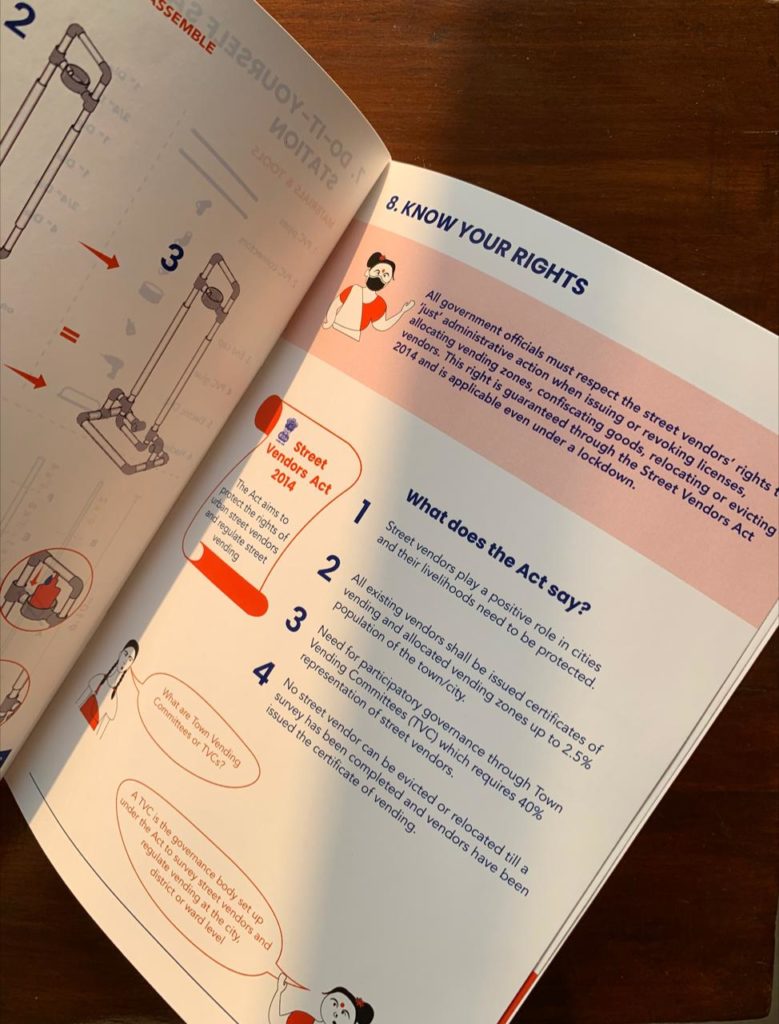

Not surprisingly, most people don’t even know what is a masterplan and how it affects their lives directly. In addition to architecture, Social Design Collaborative’s work revolves around communication through the use of its design and graphic skills in breaking down complex concepts such as public policies and working on the representation of communities that are often left out in the planning of policies. She cites the example of the Street Vendors Act 2014 which the government came up with recently. “Our work bridges the needs of these communities and government initiatives – often the authorities are not aware of the existence of these communities,” she says, adding that it’s important for everyone to know how the masterplan affects their lives.

Working with a team comprising just three other people, Ms Janu stresses that working in collaborations is her strength. And being a female architect in a largely male-dominated industry has a lot to do with her modus operandi. “Women are good at working with people. The idea of a singular heroic male figure who is going to save the day is a myth. A lot of architects fashion themselves around this idea, something that anyone who has read Ayn Rand’s Fountainhead will be familiar with. I don’t subscribe to that notion of design and architecture. Gender is a social construct and because women have had to adjust and adapt to many situations within these constructs, they have become good at people-centric work,” says the architecture activist, who did part of her senior school education at Singapore’s prestigious Temasek Junior College.

Growing up, Ms Janu wasn’t sure of her career choices although she knew that she would like to do something creative that involved skills such as drawing and making things. “Like any good Indian student, I studied mathematics and physics because it was understood that I’d pursue engineering. That’s what my parents wanted me to follow. After high school, I saw an ad for an architecture course at the School of Architecture and Planning in Delhi and it seemed like something that would work for me,” she says, adding that her parents grew up in a village before moving to the city where her father went on to pursue a professional career in the banking sector, while her mother is a teacher, and sister an animator.

“As architects, when we design buildings that pander to oppressive regimes, we become a tool of their power play. That said, every architect is free to choose their direction and as humans, it’s only natural to be attracted to where power lies.”

Swati Janu

Ask her if she was always driven towards community architecture, and she replies somewhat bemused. “On the contrary, I wanted to be a starchitect like Zaha Hadid or Frank Gehry. In architecture schools, students are fed with such ideas that this is what is seen as good architecture. It takes a lot of time to unlearn that,” she posits. “There’s, of course, a place for people like Zaha Hadid. We need all types of architects and there isn’t a singular idea of architecture.”

Ideologically, Ms Janu’s beliefs are at odds with those of the late Pritzker laureate’s. She cites the example of the construction of a sports stadium in Qatar, during which many workers had died due to poor working conditions. Ms Hadid at the time had created a controversy by stating that the workers’ death wasn’t her responsibility and that she was “merely an architect”. “I don’t agree with that as an architect. We can’t isolate ourselves from social issues around us and that’s when I was truly compelled to follow the direction that I now do,” says Ms Janu, exerting that buildings are a manifestation and display of power. “As architects, when we design buildings that pander to oppressive regimes, we become a tool of their power play. That said, every architect is free to choose their direction and as humans, it’s only natural to be attracted to where power lies.”

Unsurprisingly, her heroes are architects who have long championed the cause of marginalised communities and empowered them. “I like Laurie Baker for his use of low-cost materials, Yasmin Lahri from Pakistan for her community projects, and Francis Kere’s work in Burkina Faso. German architect Anna Heringer’s community projects using low-cost, sustainable materials are also the kind of projects that I keenly follow,” she concludes.

See the full image gallery here:

All images courtesy: Suryan Dang and Social Design Collaborative

You might also like:

Anandaloy community project by Studio Anna Heringer announced winner of OBEL Award 2020