Creative pursuits and business savvy are not mutually exclusive yet most designers fail to achieve the large-scale success they had set their sights on. Focused on the creative and production aspects, such as conceptualising, sourcing material suppliers, prototyping, finding suitable studio space, and skilled craftsmen, it is no wonder that they often struggle to collaborate with the right manufacturers, suss out new markets for their products, and broaden the commercial outreach of their brands.

To address this set of challenges, DesignSingapore Council (DSg) launched its Business of Design (BOD) programme back in 2019. Responding to its open call, eight design studios finally were picked. One of the key components of the programme is to provide mentorship by seasoned industry experts – the pilot project saw the involvement of renowned Singaporean designer Nathan Yong, former Wallpaper editor Tony Chambers, Lin Wei, the founder of United Design Practice, an award-winning multi-disciplinary design studio, and Italian marketing consultant Rita Bonucchi – in addition to matching them with manufacturers and connecting them with a broader set of players in the international design ecosystem.

As DSg launches the second iteration of its BOD programme this year, DE51GN speaks to the founders of four out of the eight participating studios from the inaugural edition to find out how the initiative has provided them with the necessary support on their individual journeys, the challenges, and how well-positioned Singapore is as one of the creative capitals of Asia. The four participants, who are flying the Singapore flag high overseas, are Gabriel Tan Studio, wohabeing (part of the renowned WOHA Architects), Scene Shang and Olivia Lee Associates.

Gabriel Tan’s eponymous studio has designed furniture and products for such international names as Blå Station, Menu, Design Within Reach, The Conran Shop, Ishinomaki Lab, Lemnos Clocks, Authentics and Abstracta. Mr Tan is also the creative director of Turn handles, Japanese furniture brand Ariake and Portuguese craft brand Origin. His works have won the Industrial Designers Society of America’s IDEA Award, Japan Good Design Award, the President’s Design Award in Singapore, and have been exhibited at design fairs globally.

wohabeing is a design brand by WOHA, an award-winning Singapore-based architectural practice that has gained global recognition for integrating environmental and social principles into every stage of the design process. The latter which has garnered several President’s Design Awards, has designed interior objects for close to 30 years, in the context of their architectural projects.

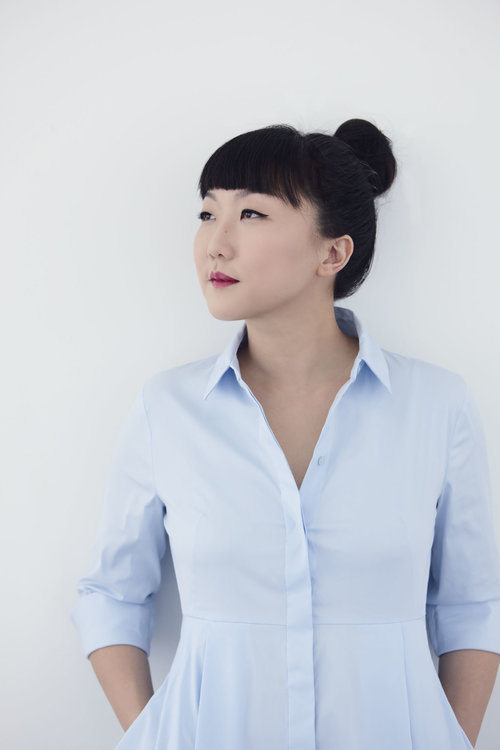

Olivia Lee Associates is a multidisciplinary studio grounded in industrial design, but spanning product to spatial design, research insights to ideation with the goal of creating unique experiences. It has produced work for international partners such as Hermès, The Balvenie, Samsung, Mathmos, Bank of Singapore and the British Council. Principal designer Olivia Lee’s works have been presented internationally in Europe and have been featured in global publications such as Wallpaper*, Icon, Dezeen, and Intramuros among others. In 2018, she was named as one of Dezeen’s “Top 10 Designers to Watch from Milan Design Week 2018”.

Scene Shang, founded by Jessica Wong and Pamela Ting, is Singapore-based contemporary furniture, homeware and lifestyle brand with roots in a rich Asian heritage. The brand works closely with traditional artisans from Asia to reimagine the silhouettes of yesteryear for the urban home, amassing in a trove of heirloom furniture and decorative fittings, each their own stories to tell. Among its award-winning products is the SHANG System – a modular storage system that combines the best of traditional Chinese design and contemporary sensibilities – which received a special commendation in the President’s Design Award in 2014.

Having made a mark in the global design field, how would you describe your journey so far? How has the BOD programme helped you in pursuing commercial growth opportunities?

Richard Hassell (wohabeing): We’ve been designing interior objects as part of our architectural practice for close to three decades, and have a very extensive back catalogue. Some of these objects are part of the design of very popular resorts, like Alila Villas Uluwatu in Bali, which means people have been using WOHA-designed products for a while now. We have been getting a lot of feedback from the hotels and from guests themselves, asking where the pieces could be purchased – so we knew that there is consumer demand for our designs.

We always planned on taking our furniture and other interior objects to market, but because architecture is our core business, it took us a while to make it happen. The final push came when we were named Maison & Objet Designer of the Year, Asia, and were asked to exhibit pieces at Masion & Objet in Paris. That’s when we decided to start our one-year wohabeing pilot project together with six maker partners to see what the actual market response would be.

We were very happy with the response and feedback at various exhibitions in Paris, Milan, and here in Singapore, and we garnered a lot of positive media attention. We also realised after completing our pilot project that we needed to tweak our business model to suit our strengths, which is what we were able to do with the help of the Business of Design Programme. After working with Rita Bonucchi, our consultant/mentor, we are now ready to switch gears and have created a licencing package to take wohabeing into the next phase.

Gabriel Tan: I believe we (myself and my team at Gabriel Tan Studio, Studio Antimatter and Origin) are at the start of a journey and I am grateful for the right opportunities that have come our way since we began in 2016. The first year was actually really tough but we are thankful that from 2017 onwards, the company was growing year-on-year until the pandemic. For me, the BOD programme was more about pursuing long-term growth opportunities. I had the chance to meet with and present my works to companies I otherwise would not have been able to reach easily, and this starts the conversation with them about the possibility of future collaborations. But nothing is taken for granted of course, as much work and time are needed to build the trust between these companies and my studio.

Pamela Ting (Scene Shang): Our journey stems from a place of genuine love for culture, heritage and beautiful spaces and pieces. We started off decorating our shared flat in Shanghai as interns there and fell in love instantly with the rich culture and the stories behind every symbol, emblem, pattern. Today, we still fall back on that to create our pieces, they need to tell a story on top of being a well-designed piece of furniture. The BOD programme paired us with mentor, Nathan Yong, who is not just a great designer but also has a keen sense of putting design and business together. That has definitely helped us in changing a few perspectives, and to refine our goals and strategy.

Olivia Lee: Since founding my practice in 2013, Olivia Lee Associates has become an award-winning and internationally recognised multidisciplinary design practice. Over the years, I have leveraged my industrial design background and developed a nuanced and narrative-driven approach that is agile yet distinct. As such, it has attracted commissions and commercial projects across design strategy, user research, art direction, brand development, interior and product design, interaction and experience design.

In these eight years, my studio has worked with global brands such as Hermès, Petit h, Samsung, William Grant & Sons, Neolith and Wallpaper* Handmade across sectors as diverse as luxury, technology, lifestyle, materials and craft. In 2018, I was named by Dezeen as top 10 designers to watch at the international Milan Design Fair, among other recognitions.

I see BOD as an accelerator and business mentorship programme. For that, it has been a real privilege to work with someone as experienced and reputed in the industry as Tony Chambers, former Editor-in-Chief of Wallpaper* Magazine.

To succeed in design, it is important to have a global outlook and a desire to connect across cultures. Tony and his team are not only highly connected, more importantly, their cultural barometers also are on point and their introductions carry weight. The in-depth conversations and meetings we have had throughout the course of the programme, have really helped clarify our business strategy and ambitions for internationalisation. They remained encouraging and supportive even as the condition of doing business changed radically in 2020.

As we emerge from the Covid-19 crisis with a sharpened strategy, we are looking forward to set in motion the plans we made to grow the studio.

Increasingly, design culture is evolving from being a consumer sector to manufacturing in Singapore, albeit on a rather low-impact scale. What are the biggest challenges you face as a designer in Singapore?

Jessica Wong (Scene Shang): Initially, we faced challenges in finding makers locally, as either local makers did not want to accept our initial lower quantities, or they had their production out of Singapore and were acting more as a go-between. This led us to search directly for makers overseas in China, Vietnam, Malaysia, and currently, Indonesia. Operationally, there was a lot of investment into sampling and testing, as well as face-to-face visits and meals to build relationships and trust for strong partnerships with our overseas makers. We also find that it’s very important to be able to visit and see the actual production facility and processes to ensure the quality and outcome we desire for Scene Shang, and this required us to travel a lot in the beginning.

Gabriel Tan: The biggest challenge we face is the technical limitations with regards to furniture and product manufacturing in Singapore, techniques, such as 3-dimensional bending of plywood, foam moulding (in sofa production) or glass blowing are not possible to find locally. I have noticed that there is a revival in the culture of making in recent years with the emergence of self-taught craftsmen or young craftsmen who have gone overseas for apprenticeships and returned with new skills and we have collaborated with such talents for prototypes (such as J Meyers leather), but on a more industrial scale, it is still difficult to find support in the latest manufacturing innovations. The other challenge is that the number of Singapore-based furniture manufacturers that work with external designers is also few, which means there is only a handful of potential clients for a furniture designer who wants to do design consultancy work locally.

Richard Hassell (wohabeing): It is very expensive to manufacture in Singapore, and even though it’s a great place to do prototyping for certain objects, it is difficult to make things here for the consumer market. The separation from the process of making is not good for design, because the feedback process of working with the makers is not available. However, it is a convenient hub for manufacturing in Malaysia, Indonesia, and Thailand and even the Philippines, Vietnam or China. But even with the proximity, it is difficult to spend enough time with the fabrication activity.

Many cities in Asia vie to be the hub of design, Singapore being one of them. How do you reckon are we positioned to establish Singapore as a forerunner among Asia’s creative capitals?

Gabriel Tan: Singapore can benefit by having a tougher stance on intellectual property infringement. We need to have regulatory bodies and watchdogs that call out businesses and manufacturers that disregard furniture intellectual properties, and have a legal framework that supports designers or companies whose IP has been infringed, whether it is copyright, design registrations or patents. I have had countless conversations with various industry stakeholders over the years over this issue and many designers and even international brands have a defeatist attitude on this issue in Singapore, with the general consensus being that it is a futile battle that is difficult to win. But I do not believe that is the case and if Singapore can do more to protect the IP of its designers and companies who are doing business here, we will start to thrive more as a design-driven city, and benefit from greater external perception as well as giving the local creative industry a more positive energy and outlook from within.

Olivia Lee: I believe every creative capital has its unique positioning in Asia’s ecosystem. I think a good creative capital is one that recognises both the economic and cultural significance of design. Design for business is a rational and near-inarguable approach because its economic impact is justifiable and demonstrable. Design as culture is harder to measure, but no less important because it is really in the accumulation of soft power that makes a city a true creative capital.

I think what Singapore is doing right is in grooming world-class creative talent, seeding design entrepreneurship and encouraging the internationalisation of home grown design-led brands. I see these as efforts to externalise and export our brand of creativity that is confident in its Singapore origins, whilst holding its own globally.

As we grow confident in supporting both the economic and cultural aspects of design, my utopian wish is for greater patronage and affordance for design white spaces — programmes that support fresh, experimental and unconventional thinking. It could be modelled after highly competitive prizes like the MacArthur Fellows Program or design residencies that welcome open-ended design outcomes. I think that would really position us well as both lynchpin and patron of design, a true creative capital for the region.

Scene Shang – Jessica Wong: I think we’re in a good position to be established as a forerunner among Asia’s creative capitals. In the last five years, there has been tremendous growth of interest and participation locally in the design scene, where not only good design is being created, but also, people in Singapore are getting increasingly interested in good design and recognise the value of it, creating further demand. This creates a good holistic environment that can help the design sector to grow and make us Asia’s creative capital.

Richard Hassell (wohabeing): Singapore is well-positioned in many ways to be a creative capital, with a very international, English-speaking business-friendly culture and systems. It is less strong in popular culture, with a small population that cannot support large-scale music, film and television, so it is more of a consumer than a producer of popular culture, which makes the design culture a little less grounded in a broader cultural conversation. However, the internationalisation of popular culture converging through digital media is changing that, and culture is becoming more located in tribes across locations rather than within nations. In this new landscape, Singapore is well-positioned, being an avid international participant in trends, and with a totally connected, always online population.

Considering we have world-class academic institutions where creative subjects are given much importance, and a pool of growing talent, what can we do to bring more entrepreneurs to invest in the local industry and make design manufacturing in Singapore an attractive proposition?

Gabriel Tan: We can possibly reach out to manufacturers who are skilled in certain manufacturing techniques (eg. PET Felt moulding or 3-dimensional plywood bending) or product categories – for example, chair production that is not available in Singapore – and attract them to set up a manufacturing branch here with incentives or other forms of support. This will promote the transfer of knowledge and technology, as well as create more jobs in furniture design and manufacturing locally.

Richard Hassell (wohabeing): The world is going through a series of shocks and restructurings which makes it difficult to anticipate the future. Singapore is at the coalface of the changes, being very much at the mercy of the international situation. Singapore is a good hub for creating businesses that serve the huge populations of Asia, and draw on the variety of manufacturing options around the region. Being so small, it is a good place to focus on the world outside, and see the big picture happening across countries, and then design products and experiences that reflect this view.

Jessica Wong (Scene Shang): I would like to see more programmes like the Business of Design continue to help transform design companies to become attractive to be invested in. Programmes that could also match-make international entrepreneurs/businesses with local design companies to work on a single project scoped to a theme, to kick-start and test out the synergy between both parties before committing fully could also be a way of getting more entrepreneurs to invest in the local industry.

There is a lot of impetus provided by the authorities here such as DesignSingapore Council to drive a design-centric culture and educate society-at-large. From your perspective, what are some of the significant developments in the industry as a result of this push?

Richard Hassell (wohabeing): There has been a big shift in the understanding of design in both business and consumers through the educational and promotional activities of DSg, as well as within the public sector. The younger generation is much more design literate and as they become creators and decision-makers the designs and products will be increasingly sophisticated and relevant.

Pamela Ting (Scene Shang): With the recent pandemic, there is definitely a lot of support in the design and arts industry to keep it going. Even prior to the pandemic, the Business of Design programme is one such example to help design companies look outside of Singapore. There are also other forms of initiatives like collaborations between SFIC and ESG on the DIP programme.

Gabriel Tan: I see that many companies are interested in design thinking and strategy for business transformation and paradigm shifts and that is a positive development.

Intellectual property rights remain a big challenge in the industry the world over but more so in Asia. How can designers, especially in the Singapore context, safeguard themselves?

Jessica Wong (Scene Shang): As mentioned earlier, when working with maker partners, we believe in doing due diligence and checking out the production facilities as well as building trust with our maker partners. There are also safeguards like applying for IP registration for your designs in the respective country markets. You could also split up parts of your design to be made by different makers so that it makes it more difficult to create a complete replica of your design. For example, where possible, Scene Shang has our signature brass hardware like handles and labels customised by a separate maker from the furniture maker, and we only send the amount needed so that we can ensure that our products cannot be replicated easily or fully.

Olivia Lee: I actually think that designers are intimately aware of their intellectual property rights. It is heartening to see Singapore’s community of creative professionals supportive of each other, huddled in conversation on how best to safeguard themselves and getting educated on intellectual property law. As a creative capital, the question we should be asking is how can Singapore foster an environment that recognises the originators of IP, better protects designers’ intellectual property rights, enforces these rights, and discourages exploitative practices that come with uneven power dynamics.

Richard Hassell (wohabeing): Well, you can always register designs or patents, but that does not necessarily deter people from copying your work. It’s incredibly difficult and costly to take legal action against people who copy intellectual property, especially if they’re in a different country. But we have noticed that with social media now being one of the driving forces in showcasing design, knockoffs are easily spotted and copycats might be deterred if they get publicly identified. Clients will also be more aware of whether or not they are buying an original. Non-Fungible Tokens are a potential game-changer for authenticity for collectible items both digital and real. Singapore should be a leader in this field.

Gabriel Tan: I believe that it is not a case of designers not wanting or unwilling to safeguard themselves, but is more that they are not confident that in the event of an infringement, they can win a legal battle against a company who has infringed on their copyright or design registration, even if they have the finances to litigate. This is because the culture of respecting design IP is still new in Singapore and Asia in general where you can walk into a five-star hotel or a bank and see imitation furniture used openly whereas in some countries this is absolutely forbidden.

If Singapore can adopt a tougher stance on this, then we will see a huge shift in business culture that will ultimately benefit the furniture industry, design industry, and related creative industries in Singapore. Designers can form groups to pressure the authorities to lobby for this cause, as well as have collective social media action against companies who are infringing local or international design IP.

You’ve worked with international manufacturers, and have the knowledge of how these markets work. What according to you makes a “Made-in-Singapore” product attractive to buyers overseas?

Gabriel Tan: Most of my furniture is actually not made in Singapore but manufactured by my clients in their factories which are in other parts of Asia or Europe. They are designed in Singapore. It makes sense to manufacture as close as possible to the end consumer but only if there is the manufacturing infrastructure as well as a pool of skilled labour. Then, of course, there is the affordability factor with regard to manufacturing costs – rent and labour costs. The attractiveness of working with a Singapore-based designer is the local insight to the Singapore consumer mindset, retail and contract scene as well as that of the surrounding regions (as Singapore is often seen as a gateway market into Southeast Asia).

Of course, we can try to attract clients by offering the above insights to them and helping them connect to the right partners so that whatever we design can help them enter our home market, but at the end of the day, it is also about design philosophies, intellectual and creative chemistry between the designer and the company/brand to determine if a collaboration will happen, or not. The pairing of a designer and a manufacturer is often not a one-off relationship like an interior design project, but it is almost like a marriage, where one can count on each other for long-term support and grow together.

Pamela Ting (Scene Shang): I believe that a piece that is “Designed-in-Singapore” is also extremely attractive to overseas buyers. While we as a company or as designers want to, as much as possible, have the “Made-in-Singapore” mark and support local craftsmen, the availability of manufacturing business or skilled craftsmen is scarce and fast fading, and it becomes niche and costly to have completely “Made-in-Singapore” pieces.

Richard Hassell (wohabeing): Singapore’s growing brand as a green, multicultural city of the future is now very valuable, as it positions Singapore design and products as items from a desirable future. Singapore is also seen as a forward-thinking, developed nation that values quality and smart design, which makes products “Made in Singapore” attractive for the market.

You might also like:

Nathan Yong: We need to augment our Singapore design brand with better research and quality

Exhibition at Singapore’s National Design Centre highlights the emotive influence of F&B packaging