Mumbai-based globally-acclaimed architect Mr Sameep Padora’s eponymous practice is widely regarded for its research-oriented projects that take a deep dive into not just the context but also the socio-cultural and socio-economic dynamics of the projects. Back in 2016, Mr Padora had authored a book called In The Name of Housing, A Study of 11 Projects In Mumbai (above; photo: Kunal Bhatia) which has now been republished by Dutch publishing firm Nai Uitgevers Publishing with updated essays and data as part of the international edition of mass housing typologies in one of the world’s densest cities – Mumbai. His project the Maya Somaiya Library in India’s western state of Maharashtra won the top honours in the education category at the 2019 World Architecture Festival in Amsterdam.

Jetavan spiritual and skill development centre for the marginalised communities; photo: Edmund Sumner

In an exclusive interview with DE51GN, Mr Padora discusses the role of chawl public housing that is unique to Mumbai, its organic evolution, and the city’s other urban challenges that are intrinsically related to housing.

How has the density impacted the Covid-19 situation in Mumbai?

Because of the spatial connotations of what this virus can do, density is going to be challenging. But any other crisis further brings to the fore any faultlines that have already existed in our space. While Covid-19 in that sense has been a wake-up call, the indication of what densities like the one we have in Mumbai, if not reasoned and addressed with the lens of liveability, quality of life, ventilation, access to healthcare infrastructure, any city will turn into a nightmare. So to answer directly, yes, density is a challenge especially when you have a bottleneck in social housing, healthcare and transportation.

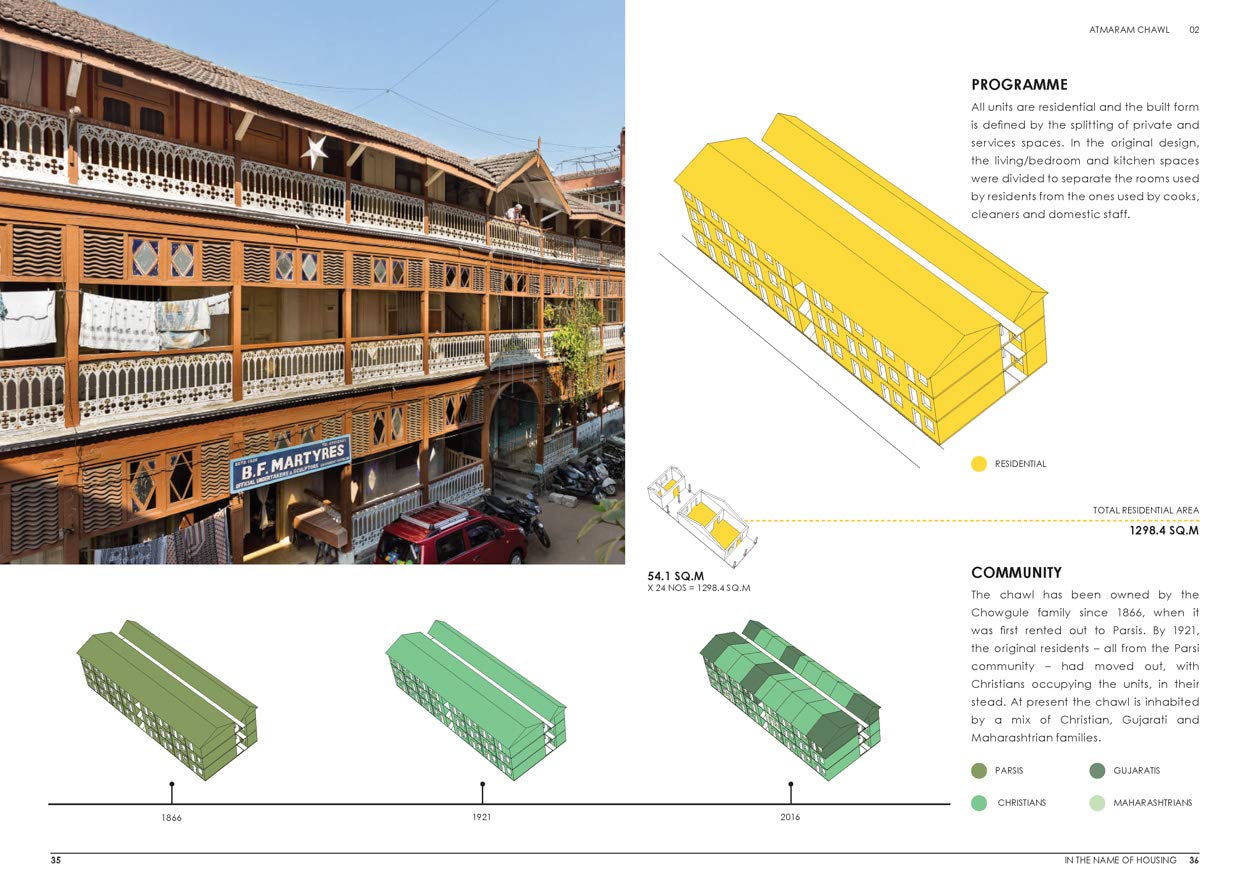

Chawl typology in Mumbai has been discussed in great detail in the book. Is that the equivalent of low-cost public housing?

The chawl started off as a means for migrants who came to the city to look for work to provide cheap housing for them. A lot of them were actually privately built. Once we had the textile boom in Mumbai back in the second half of the 19th century, when the textile mills really proliferated the city, the state, at that point, realised that housing was needed to accommodate the huge number of workers who were working in the mills. That’s when they set up the state-built chawls as well, some of which we have covered in our book. A huge number of chawls were built by private individuals, and the nature of those is extremely varied – we have analysed and documented a few in the book as well.

Metaphorically speaking, we have only managed to touch the tip of the iceberg in the book. Huge amount of data that still needs to be gathered. I think what has happened with the chawl is that even though they started off as housing for workers without families, over time, they’ve mutated into dwelling units for families – in fact, for generations. They’ve made changes into the architecture of the unit itself, so they now have toilets as part of the units – previously, they would share a common toilet with the other residents of the building; kitchens have been added, some people have added mezzanine and details to reflect the fact that space needed to be flexible despite the fact that it’s very small. These are the kind of things that make these chawls a fascinating study.

Is there a set of building codes that are considered while making these additions and alterations to the units?

Changes are made despite the building codes. The funny thing about these building laws is that there is not a line drawn in fine sand and say that this is legal or that is illegal. We know from the nature of our cities that there are various definitions that come out to explain the built phenomena. For instance, extralegal – a word we hear often to define this entire space. The law is more like a feared condition than a line in the sand. It’s really this ability to navigate this field that allows for these projects to happen. They are also extremely need-based. They are not built for speculation, it’s built to use. Which in some sense also tells us that maybe building codes need to see what’s happening on the ground and reinvent themselves. In fact, our new research is exactly about that to learn what kind of building codes would allow certain kinds of architecture and socio-fabric dynamics to work out within the city.

Courtyard typologies exist around the world. Is there a parallel to Mumbai’s chawl courtyard concept?

Given the kind of climatic conditions, courtyards have traditionally been part of our architectural fabric. The interesting thing, however, when you start looking at climate like ours – and Singapore to a certain extent – is that we don’t need to insulate as much as European countries. We don’t have a winter season that needs to be cut off completely. The courtyard can function all year round. And because the houses that you live in are very tiny, it allows the courtyard to take on some of the programmes that would typically have been conducted within the realms of private space. These courtyards sort of become community living rooms which is fantastic but it also brings into question the nature of what is public and what is private. Those binaries that we typically see in apartment buildings or contemporary lifestyle is not how it is viewed when space is really a luxury, and whatever space you get is what you will actually use. That’s why the courtyards and corridors are critical elements to think about when you think of affordable housing.

So far, the narrative driving urban development is that density drives sustainability. But in light of the new norms being embraced due to the ongoing pandemic, experts are now saying that the focus should be on intensity and not density. How does that work in the context of Mumbai, one of the densest metropolises in the world?

That’s a good question. The answer to that is also very specific to the context of the city that we speak about. In Mumbai, there is another factor that comes into play which is the idea of time. For instance, how people live in chawls or even in slum housing where there are people who actually use the house as a dormitory at night and during the day, it becomes a workshop to conduct some home business to generate some income. In this case, a house is also a place of production. It’s in that that there is a value that relates to the idea of intensity where programme is not partitioned off in terms of geography and time as well. If we’re able to manage that, then there is an additional aspect of dealing with density through the lens of intensity based on the idea of use over time. I’m not proposing something new; it’s already happening in the city. Unfortunately, we tend to see this as a problem and not a solution. The minute you shift those lenses, automatically there are avenues that talk about how Mumbai as a city already operates at a spatial efficiency because of the way it uses space and time. If we are able to articulate that within the formal city, then we can all learn from it.

“We know from the nature of our cities that there are various definitions that come out to explain the built phenomena. For instance, extralegal – a word we hear often to define this entire space. The law is more like a feared condition than a line in the sand. It’s really this ability to navigate this field that allows for these projects to happen. They are also extremely need-based. They are not built for speculation, it’s built to use. Which in some sense also tells us that maybe building codes need to see what’s happening on the ground and reinvent themselves. In fact, our new research is exactly about that to learn what kind of building codes would allow certain kinds of architecture and socio-fabric dynamics to work out within the city.” – Sameep Padora, founding principal, Sameep Padora & Associates

People spend a fair amount of time on the daily commute to work. How is the transport infrastructure intertwined with housing in Mumbai?

There are a couple of answers to that. First, if you look at how Mumbai operates – it’s become even more evident during the pandemic – where the formal city and apartment blocks operate on the adjacencies of the blue-collared workforce that resides in chawls and slums, which are located smack in the middle of the city. That kind of adjacency allows for certain efficiency of movement albeit there are also the bottlenecks of health parameters and just generally in terms of access to clean water and infrastructure. But there is already the sense that adjacency exists, however, the aspiration, which is complex in some ways, is to move beyond the slum to an apartment (whether own or rented) usually means that you’ll have to move away from the city.

The state is not quite able to understand this dynamic and create a housing infrastructure that allows this co-existence to persist. Which is why you get this idea of transit, because you don’t only aspire to a house but also a car or a bike, which in Mumbai, unlike Singapore, is fairly easy to buy if you have the money. The moment you move away from the city and start commuting on bikes or cars, you automatically get the long transit time. But it’s a thin line – how do you balance aspiration with the idea of what’s sustainable? In a country like ours that is still grappling with large poverty numbers, you need to think about how to do it sensitively. That requires an incredible amount of state intervention. I don’t know whether the state actually sees that as a challenge they have to address. Maybe post-Covid-19, they will but so far, they haven’t.

As Covid-19 has forced us all to relook at the way we work, specifically in the context of Mumbai, will it save some of the transport and commuting issues, if people were allowed to work from home? More importantly, does their living environment allow them to work from home?

There are lots of blue-collared workers and hawkers who can’t work from home. So that entire economy that operates on its interaction with others is completely gone. The more fortunate people who still have a home to stay in and work from in a way that we can still do this from home, about 40 to 60 per cent of the population doesn’t have the luxury. That’s why the huge number of domestic migration took place where people went back to their hometowns.

Will these migrant workers come back to the city or is it a wait and watch situation?

There is a tendency for us to look at this situation and call it the “new normal”. I hope that we don’t forget how abnormal the situation and if we can keep our eye on the fact that we live in an extremely kind of challenging time, thanks to choices that we have made – both as institutions and individuals, there is some hope that we will be able to cost correct as we go forward. Part of that cost correction needs to be the attention paid to taking off the name from this book called “How the other half lives” and really to look at slums and settlements where the conditions are not sanitary enough. For instance, how do you wash your hands when you don’t have access to water. If we can keep our eye on the idea that we need to make a city sensitive to all kinds of class groups, then there is a chance that they might come back. But right now, it’s anybody’s guess whether the political machinery actually recognises that. It’s been done in the past after the plague of 1898, housing was built by the state to attract workers to come to the city. But in this instance, we have to see whether we still have the same foresight or drive anymore.

There are reports that a new metro line is being built in Mumbai that requires clearing out forests. How does this impact the conversation on balancing sustainability with density and development? How is this working out in relation to this infrastructure project?

Unfortunately, it’s not going too well. There was this talk about clearing out the forest area for parking bay for the metro rails. Even more damning is the coastal road project which will build a huge road project running through the western coast of the city of Mumbai. Besides destroying the ecosystem and the livelihoods of the fishing communities that live along that edge, such a project will also completely obliterate Mumbai’s relationship with its coastline because you’ll have this big road that passes over the water bodies. Again, the emphasis has shifted from being about public transport to people getting into their cars and driving from one place to another.

The coastal road project runs along the length of the city. Mumbai is not dealing with it very well in that sense. There are lots of citizen groups, advocacy groups that are campaigning against it. But there hasn’t been much luck with that.

What do you hope to achieve with Bandra Collective, a ground-up citizen initiative in Mumbai that focuses on placemaking and urban living issues?

We started it off primarily as a reaction to the fact that the state was commissioning projects within the city that had very little or no design intervention to the point that were – to put it bluntly – stupid because they were planned illogically. We said that whatever the projects that state has, we would offer our services pro bono and consult for them. Based on that, they can choose whether or not they’d go ahead with any specific project. At the same time, we also started talking to local resident groups to better contextualise our ideas and to bring the public conversation to the local councillors or the bureaucrats.

Our intention was to try and make a difference to whatever projects were already happening. But in the process, we also started creating projects that we feel certain neighbourhoods might need. We started going to the local residents of those neighbourhoods and councillors and telling them about these projects that we could do. We are talking about such projects that might happen post lockdown.

“We also have to understand that as architects and urban planners, we can’t sit back and think about the fact that a municipal councillor will come to us and hand over a project. It’s about taking on the onus and reverse engineer the process. Maybe, we need to look at the projects the city needs and be an advocate for that.” – Sameep Padora

Why is there such a lack of institutional building in India? Is it because of funding issues

The issue is not so much about funding. Mumbai’s BMC, the local municipal corporation, is one of the richest entities of its kind in the world. The issue here is that most of the projects that are done and proposed don’t really see the value design can bring through political economy where a councillor thinks that if I did that I might get re-elected. This reflects the political aspect of his or her aspirations. On the other hand, the bureaucrat who doesn’t see enough value in perhaps going against or working in a way that is different to what he is used to in terms of talking to the contractors because typically the bureaucrats only talk to the contractors. Once the project has been contracted out, the contracting firm is the agency that basically designs and builds the project. So he has no need to go to a designer or an architect or to a public space agency. They pretty much run this as a contracting job which is really the challenge.

It’s not about the funding but the lack of systemic process to configure design as part of the project. There are certain groups in Mumbai that are working towards addressing this is either through tactical urbanism or through agencies that are already networked with the state and are now hosting competitions. For example, Bandra Collective has recently won a competition to redesign a public street in northern Mumbai. Competitions like this didn’t happen earlier but there are growing changes that one can see and there is some hope that the city might be better off for it.

We also have to understand that as architects and urban planners, we can’t sit back and think about the fact that a municipal councillor will come to us and hand over a project. It’s about taking on the onus and reverse engineer the process. Maybe, we need to look at the projects the city needs and be an advocate for that.

What’s the state of urban housing in Mumbai now?

In Mumbai, the floor space index (FSI) is the currency – it is the amount you’re allowed to build. The instrument has become even more powerful than the actual end that the instrument is meant to cater to. While there are luxury buildings being built, there is already a huge amount of unsold stock of luxury buildings in the city. These are apartments that are lying vacant, which is criminal to say the least. The state has done its bit by imposing additional taxes on unsold or unoccupied units, it’s still not enough.

The prices of these private residences haven’t dropped a lot despite the fact that there are still so many unsold units. But developers also want to make money, so they are trying to figure how to build smaller units to sell and bracket it as part of affordable housing which the central government has a massive scheme for. But even if you are doing it as a small one-bedroom apartment in central Mumbai, it’s still going to cost you over Rs 10 million. But one must also consider the fact that luxury housing is linked to affordable housing as well. There is a kind of adjacency there and if you’re able to figure out a model that services both, then there is a means for us to making the city a little more human. The problem arises when even the state begins to think like a developer and not like the harbinger of social good.

You might also like: