Designing for the desert terrain is not only a matter of expertise and technical know-how from the point of view of the site topography, structural and building materials knowledge, but it requires an innate understanding of the landscape from a socio-cultural perspective. As the natural habitat of the native population in the Middle East, the arid and harsh desert milieu presents new opportunities for architects and designers to create a sustainable built environment that draws upon the region’s vernacular architecture but also leverages new technology to align with environment-friendly guidelines towards the structure as well as other considerations such as the MEP works. (Above photo: Al Faya Desert Retreat and Spa in Sharjah by ANARCHITECT; photo: Fernando Guerro)

DE51GN speaks to the Middle East’s three most dynamic boutique architecture practices that are setting new benchmarks in designing for the desert.

Studio Toggle was established in 2012 by architects Ms Hend Almatrouk and Mr Gijo Paul George , after graduating from the University of Applied Arts (die Angewandte), Vienna. The practice focuses on logical design and problem-solving techniques with a specific emphasis on architecture and urban design. Operating from its two offices in Porto, Portugal and Kuwait City, Studio Toggle has designed, supervised and handed over multiple projects including private villas, apartment buildings, public pavilions and retail and hospitality interiors. Its recent projects such as project Khat’ in Saudi Arabia’s Al Ula heritage site and Ternion in Kuwait have won much critical acclaim.

Khat boutique eco-lodging concept for Saudi Arabia’s Al Ula UNESCO World Heritage site by Studio Toggle.

Khat is a collaboration work of Studio Toggle architects with Kuwaiti artist Ms Aseel AlYaqoub, as a part of a competition, to design a small lodging in AlUla, the home of the archaeological site of Al-Hijr (Madain Salih), the first UNESCO World heritage property to be located in Saudi Arabia. AlUla’s history is memorialised as past, crystallised into precious moments curated by archaeologists, historians and locals.

In the midst of its valleys, the craftsmanship and scale of the Nabataean tombs bring the imagined past to the present times. In the centre of this valley, there lie three large rocks that apparently have fallen from the sky, mirroring their surrounding landscapes. In aerial view, vast amounts of sand are dotted with intermittent mountainous forms that suddenly multiply in a disorderly fashion.

Khat boutique eco-lodging concept for Saudi Arabia’s Al Ula UNESCO World Heritage site by Studio Toggle.

The grand shadows of the mountains and a vertical shaft on one of them suggests that during heavy rainfall, this was a water source from where the water rushes down into the water basin beneath to meander into a stream towards the northern valley. In order to understand the time capsule that is this place, Studio Toggle played with the idea of creating a contradiction must exist to provide an unexpected juxtaposition. Through contrast and difference such as colour, value, scale and material, the landscape can be intensified and its history can be seen more vividly.

Khat boutique eco-lodging concept for Saudi Arabia’s Al Ula UNESCO World Heritage site by Studio Toggle.

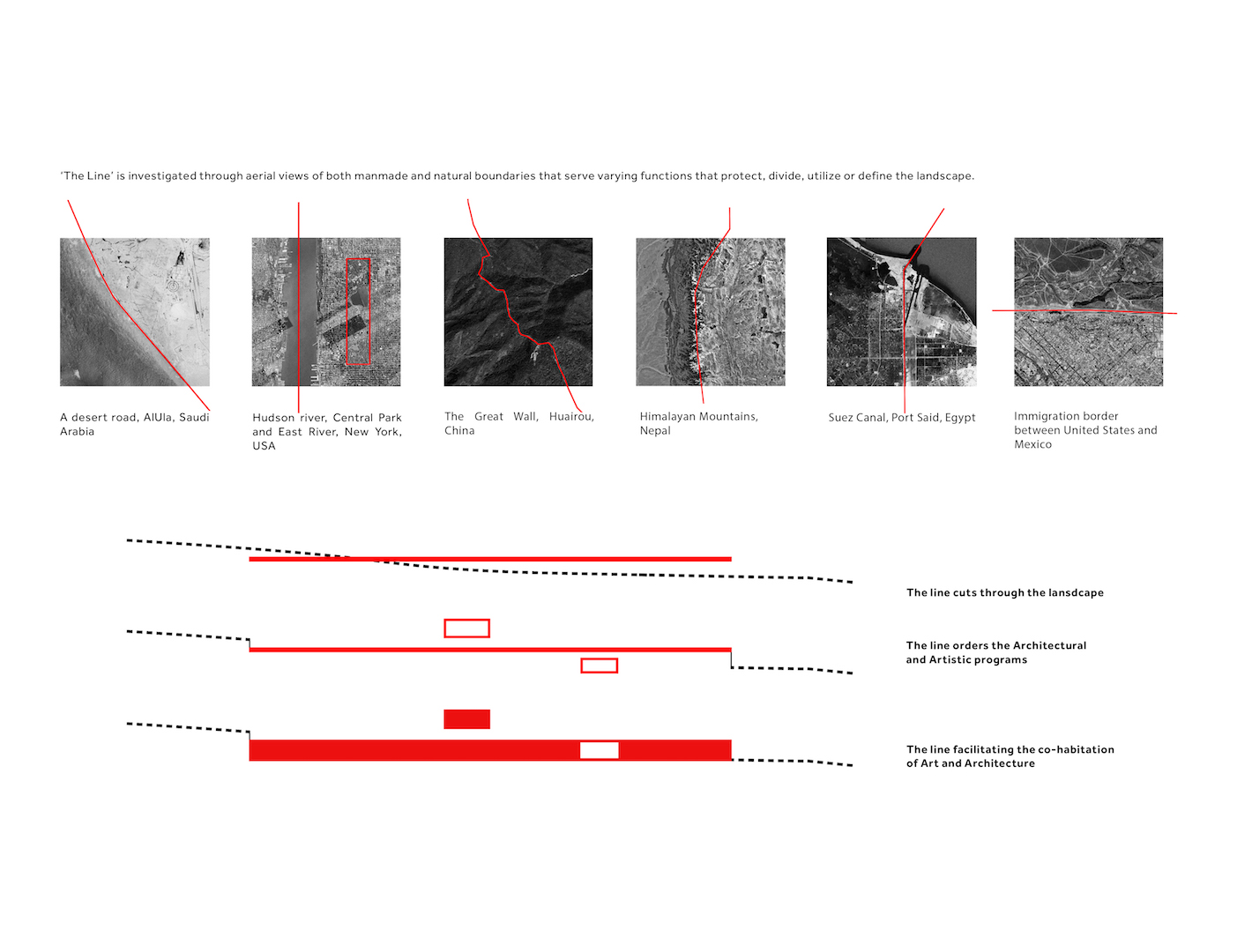

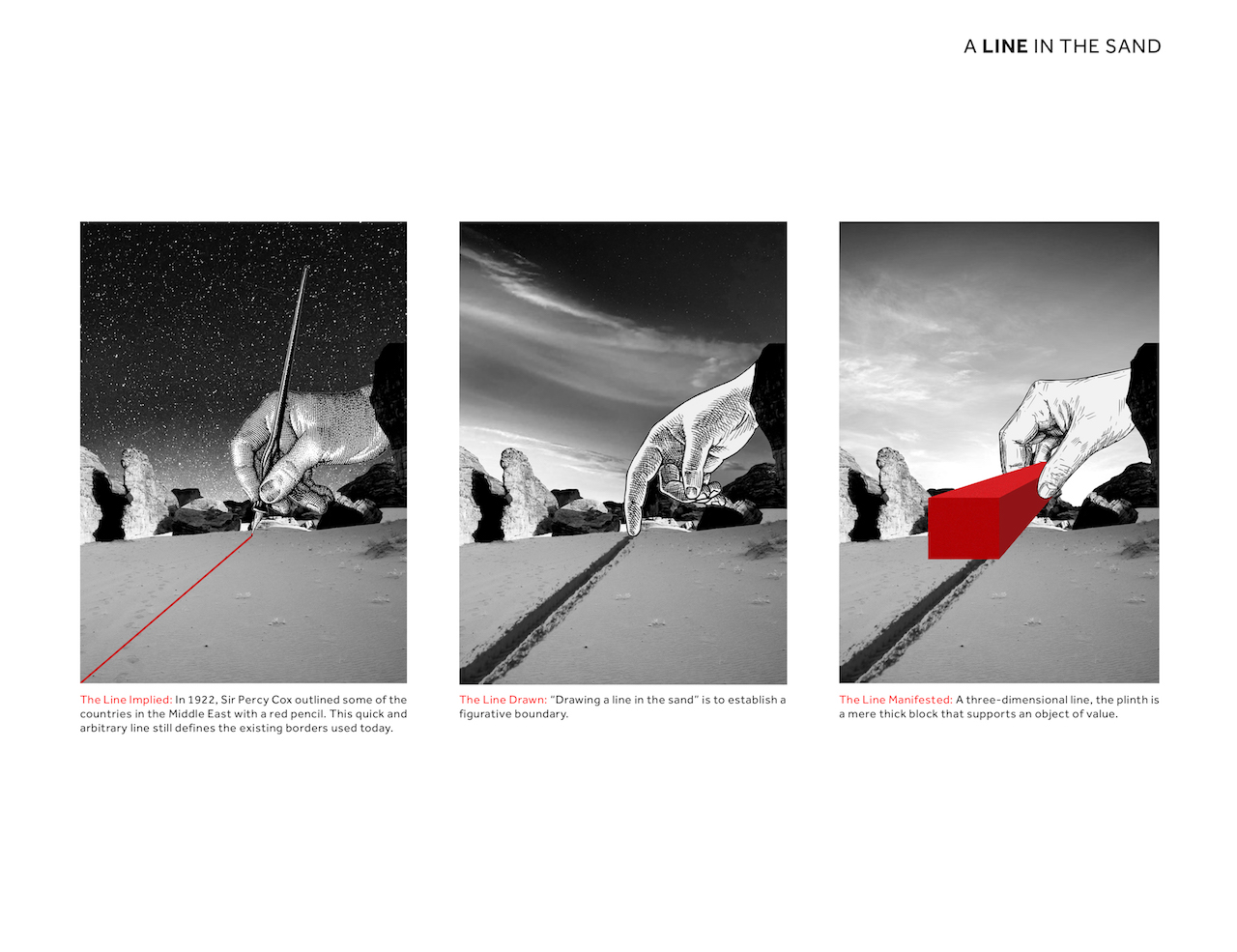

The concept “Khat” (line in Arabic) is a spatial experience whose intangible essence is suggested by the artist and formalised by the architect, to create a finite human environment within the infinite landscape of its surrounding nature. It combines man’s relationship to an ancient natural world and the 21st century human world via a minimal intrusion. An extruded line in the sand, as a symmetrical white plinth, presents a strong contrast to the irregularity of nature.

Khat boutique eco-lodging concept for Saudi Arabia’s Al Ula UNESCO World Heritage site by Studio Toggle.

Inspired from but not influenced by the Nabataean tombs, its monumental existence creates a contradiction that also eliminates a redundant and unnecessary addition to the landscape. Its form is a formal yet inhabitable gesture that cuts through the landscape, suggesting that we draw a conceptual and physical line, not between past and future, nature and modernity, but instead between dichotomising and coexisting. A white box floats over architecture that is not defined by the space it contains but by its envelope. Beneath it is an open space void of decoration, ornamentation, distractions and dialectics. Like tombs, ruins and religious icons, its formal appearance is flexible in its use, allowing for a free plan that opens up to the landscape, balancing the manmade with the natural world. Its pure form is a transitional gesture that aims to re-engage the time traveller back into the present, in order to stimulate their perception via contrasting experiences. Ms Almatrouk and Mr Gijo explain their firm’s extensive R&D-driven approach to designing for the arid topography.

What is your approach while designing for the harsh desert climate?

Designing for a hot-dry desert climate requires a complete understanding of the drastically changing weather patterns over the course of the year. Especially in the context of Kuwait and Saudi Arabia, while the summers are too hot with the temperature hovering above 50 degrees Celsius, the winters can be extremely cold with temperatures dropping down to single digits. While the majority of the year the humidity is rather low, July and August tend to be too humid to be outside with periodic dust storms that make the weather rather unbearable. This means that the building envelope has to be designed in a manner to resist these factors. Sizes and the orientation of the windows need to be studied and strategically placed to prevent undue strain on the mandatory air conditioning systems. Effective weather proofing and extensive thermal insulation is the key along with the careful selection of building materials that prevent non-desirable heat gain.

How do you achieve sustainability while keeping the intervention caused by construction activity low?

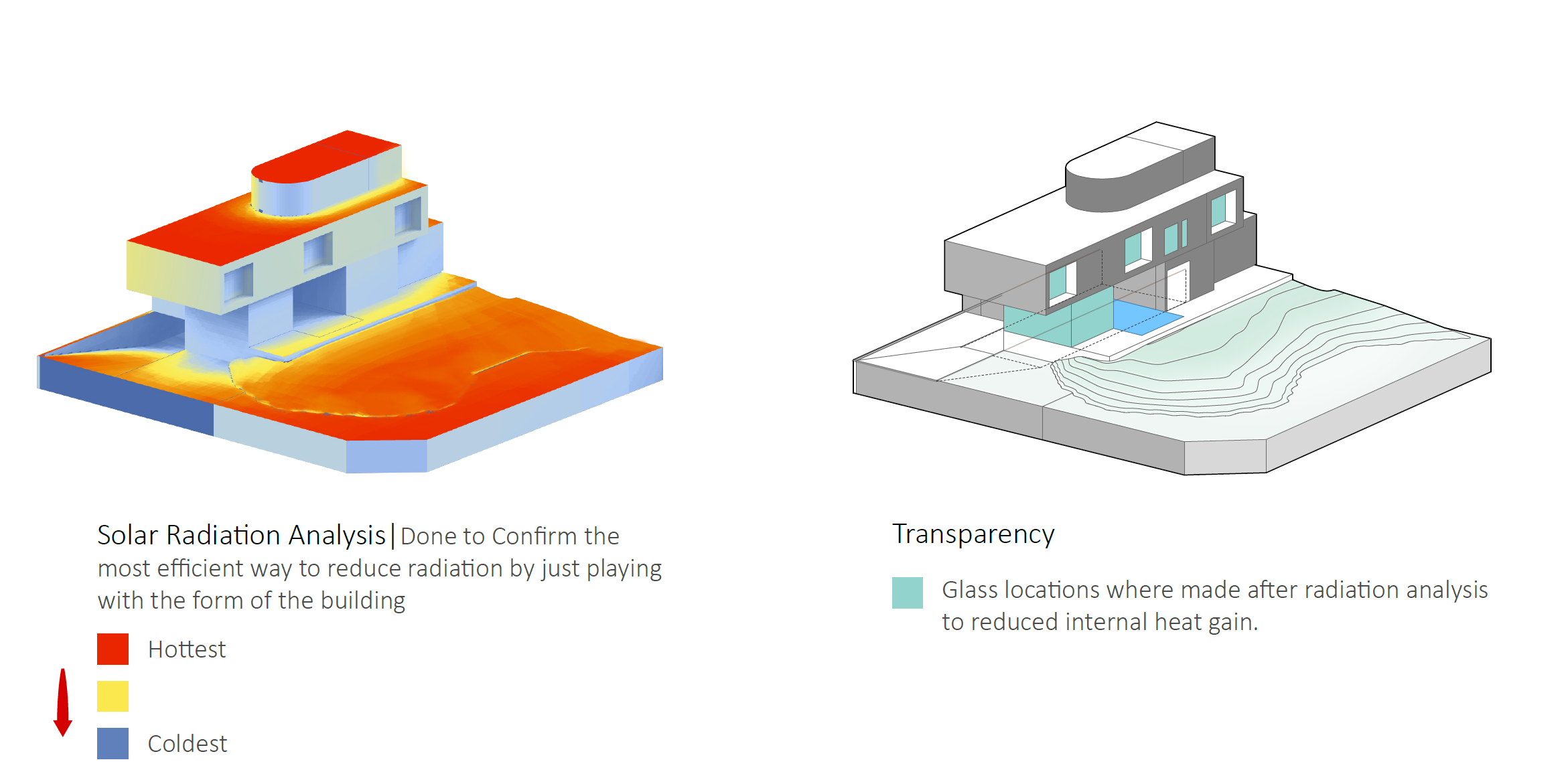

In such extreme climates, it’s almost impossible to avoid active climate control systems, which by definition are not very sustainable. At Studio Toggle, we try to minimise the impact of these systems by employing multiple strategies such as optimising the building envelope by detailed climate analysis and thermal studies. We extensively employ BIM and depend on multiple environmental analyses software to facilitate a data driven approach to building envelope design and optimisation. Example below shows the thermal analysis done for project F.LOT (2016) that helped to identify the areas of maximum heat gain and compensate accordingly.

“It’s understood that the carbon footprint of a large project is always much higher than that of a smaller project due to its sheer scale and complexity. But from our experience of operating in the region, we have realised that the large scale projects are more receptive towards the adoption of green building strategies and are far more concerned about their energy consumption and environmental impact than small scale projects.” – Studio Toggle

The strategic placement of building apertures including windows and skylights to minimise the heat gain and maximise natural light. North facing apertures are generally preferred while the south-west facades are thermally insulated with minimum openings.

Another strategy that we use is to manipulate building volumes to generate self-shaded spaces. Extensive use of cantilevers, overhangs and louvers also helps in shading larger apertures that might otherwise increase the heat gain.

We invest in high-performance windows systems and specifying materials with minimal heat transfer coefficient, and we make use of smart systems and certified equipment to reduce energy consumption. We also design the surrounding landscape to mitigate the heat gain.

How much does the scale of the project matter and is sustainability in this respect inversely proportional to the size of the development – that is bigger the project in size, smaller the sustainable impact?

It’s understood that the carbon footprint of a large project is always much higher than that of a smaller project due to its sheer scale and complexity. But from our experience of operating in the region, we have realised that the large scale projects are more receptive towards the adoption of green building strategies and are far more concerned about their energy consumption and environmental impact than small scale projects. This is generally due to factors such as higher cost of adoption (as a percentage factor of total budget) in small-scale projects compared to large-scale projects, larger developments generally benefit more from energy-efficient design and sustainability incentives, and availability of cheap and heavily-subsidised electricity

However, the adoption of cost-effective passive sustainable solutions in small scale projects is on the rise and is a positive trend in the region as a consequence of architectural activism by an increasing number of sustainability-driven architectural practices, coupled with rising awareness among clients building small scale projects.

What are the materials that work best in such an environment, according to you?

From our experience, we tend to recommend locally available materials with lower heat transfer coefficients. For example, we have developed, in collaboration with our contractors, a smooth white self-cleaning cement render that is dust repellent and can withstand extreme heat. We have successfully used this in our built projects and it remains our favourite cost-effective external finish material.

Fired brick is another cheap and locally available material with good heat resistant properties and numerous aesthetic possibilities. Omani sandstone is another excellent locally-sourced material that makes a fantastic wall and floor cladding material. As for building apertures, we always recommend double- or triple-coated low-e glazing with dust-proof thermal break profiles.

What are some of the traditional passive design strategies that work well in desert environment?

We take pride in our efforts to understand the vernacular, abstracting it and applying those strategies to good effect in a modern context. If we take houses for example, historically the enclosed spaces used to be arranged around an open courtyard. The normal practice was to wet the courtyard every morning so that the temperatures remain low due to evaporative cooling. In our residential projects we adopt this and always try to incorporate a cross-ventilated courtyard featuring a water body.

In the ‘House in Mishref’, this can be seen from the courtyard featuring a geometric fountain. In ‘Ternion Villas’ each of the three villas has a swimming pool that is the focal point of the ventilated courtyard facilitating evaporative cooling.

Cantilevers and overhangs are a recurring feature in Studio Toggle’s projects as seen here in the Ternion project.

Mashrabiya (privacy screen) is another traditional strategy that was used for both achieving a level of privacy due to the cultural norms and as a shading device to keep the sun out. The ‘House in Mishref’ make extensive use of this strategy to good effect to achieve both privacy and shade. Cantilevers and overhangs which used to be an essential feature of the narrow streets of the old Arabian town are generously deployed in our projects ‘Flot’ and ‘Ternion’.

“For desert conditions, we believe it is important to look back in history and explore how nomads and Bedouins lived. They would set up smaller temporary settlements on transit routes across the desert; these would be small in scale and of non-permanent and low-impact structures. There are rarely many permanent or large settlements throughout history that survive within the desert environment without huge consumption of energy and resources.” – ANARCHITECT

Dubai- and London-based firm ANARCHITECT known for its contextual approach has designed several projects throughout the Middle East that dwell heavily on passive design strategies for an ecologically sensitive approach to building. Among its most recent projects are the critically-acclaimed Al Faya Desert Spa and Resort in the vicinity of Sharjah’s UNESCO World Heritage site, Mleiha Archaeological Centre, and a private residential villa embedded in the desert landscape of Dubai, both in the UAE. The former is a five-room luxury property that was carved out of a defunct fuel station. ANARCHITECT’s RIBA-accredited founder and principal, Mr Jonathan Ashmore (above), explains his design approach.

What are some of the key factors while designing in the desert?

As with nearly all projects, it is imperative to understand the climate within which it sits and the impacts this will have on the building and its occupants in terms of comfort, protection and living conditions. With the desert, the climate is extreme, so we considered the specific conditions when designing our projects in the desert context.

Firstly, high temperatures during the day and low temperatures at night are overcome by providing a building with thermal mass to account for these diurnal temperature fluctuations. Solid stone, concrete, heavy-mass building material slowly absorbs the sun’s heat radiation during the day, while keeping the interior spaces cool. At night when the outside temperature drops much lower, the stored heat within the dense construction material radiates out and keeps the interior spaces warm and comfortable.

Secondly, it is also important to understand the buildings orientation to avoid designing exposed large or glazed openings on the facades facing towards the south and taking as much advantage on the north elevations to draw in natural north-light in abundance to passively provide natural light into the interior spaces.

Thirdly, one less considered factor often overlooked is the need to understand the prevailing wind directions. As the desert landscape is arid and dusty, winds can pick up the sand which then blows and builds up intensely over time against the receiving façade of the building. Creating planted barriers within the landscape can help to reduce the impact on the facade, along with providing elevated terraces to avoid low-level sand drifts and providing airflows across roof surfaces by reducing or removing parapets where sand build-up might occur according to the prevailing wind direction.

How can you build sustainably in the desert while keeping its intervention low?

With the Al Faya Desert Retreat & Spa project in Sharjah; Anarchitect repurposed and brought back to life two existing and abandoned desert structures from the 1960s. If existing structures are present on a project, the architect and client should certainly explore the possibility of retaining and reviving these if there is a relevance and suitability for purpose as a first approach to sustainability.

If the desert location has no existing structures and the project involves creating new buildings, then there are a number of ways in which the project can be designed to retain a low impact during the construction and throughout the building’s lifecycle.

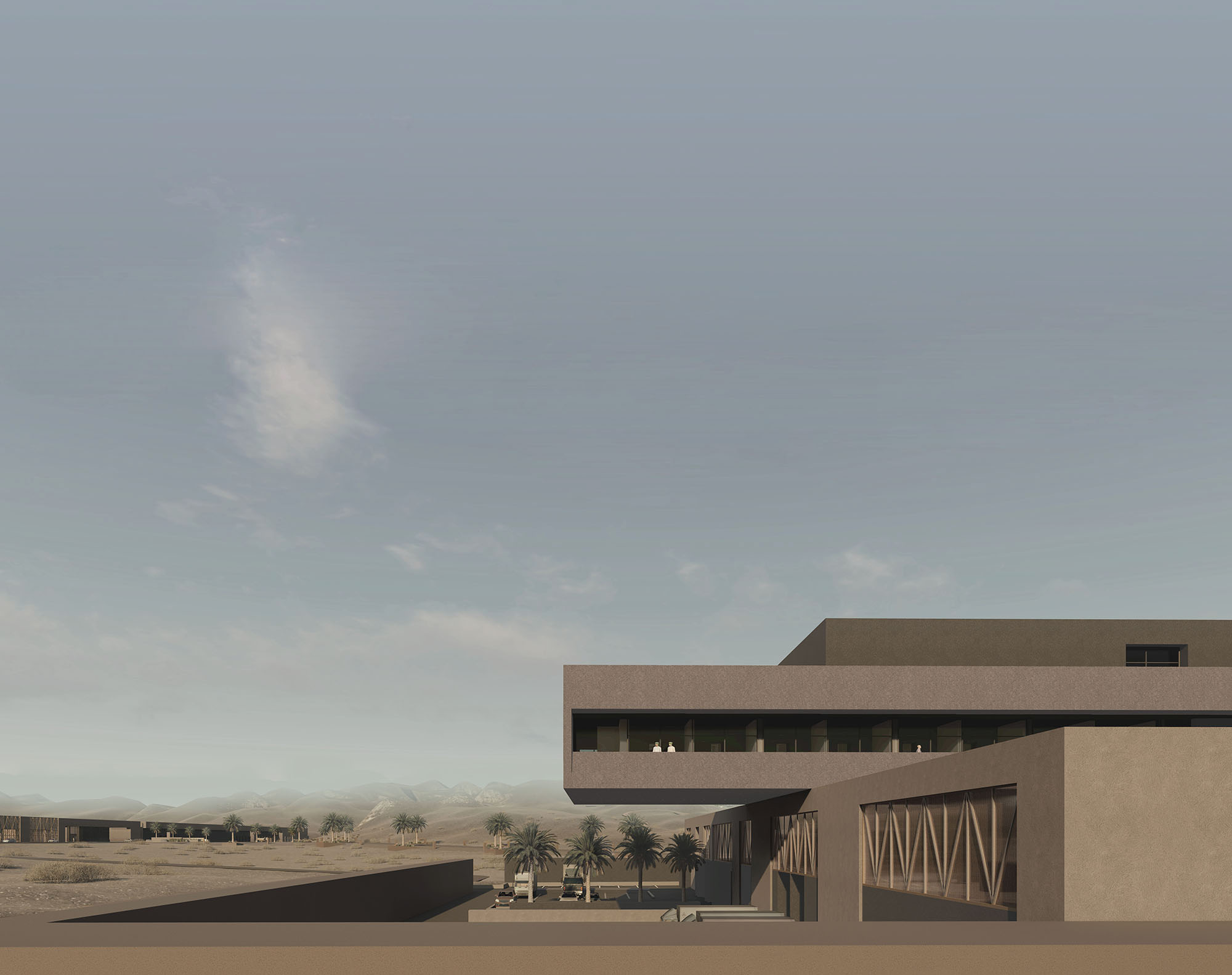

Private desert retreat currently under construction in the United Arab Emirates, designed by ANARCHITECT.

ANARCHITECT is currently on site with two private desert residences in a remote location in the UAE. One residence has a particularly difficult terrain and is positioned atop a 25-metre high shifting sand dune. Given the complexity of the context and the isolation, we intentionally designed the property so that 75% of the works are off-site construction using pre-cast, load bearing shear walls as the fundamental frame for the contemporary designed project. This reduces the amount of disturbance and construction required on site and therefore has a reduced impact on the context.

Off-grid technologies to provide power, water, waste and heating are also becoming more advanced and efficient which can reduce or even remove the need for infrastructure if it doesn’t already exist in the site location. This further offers low-impact interventions particularly for remote areas as deserts often are.

How much does the scale of the project matter and is sustainability in this respect inversely proportional to the size of the development?

Scale should ideally be proportional to the site context and the functional use of the project. Over scale often feels disconnected particularly within the desert setting as it easily becomes visually intrusive on the landscape, both close-up and from long distances away.

Scale is quite often proportionate to the energy consumption of a building, particularly within a desert setting as artificial cooling loads increase with size, so too does water and power consumption, therefore requiring more infrastructure and built-up area to accommodate and shelter these services equipment.

For desert conditions, we believe it is important to look back in history and explore how nomads and Bedouins lived. They would set up smaller temporary settlements on transit routes across the desert; these would be small in scale and of non-permanent and low-impact structures. There are rarely many permanent or large settlements throughout history that survive within the desert environment without huge consumption of energy and resources. Smaller clusters offer the opportunity to function at optimal levels if designed well, so that the proportion of the built up area can sustain its own adequate solar power generation, rainwater surface collection and solid-to-transparent ratios to offset against its own consumption. The larger this building or settlement becomes, the more difficult it is to achieve a balance; and we can hope that the advancement of technologies will offer more solutions in time to come.

“Taking cues from local vernacular architecture is a primary consideration for us. Rather than importing architectural styles, it is important to learn from the surrounding environment. Traditional sustainable solutions are often beautiful, and usually simple and cost effective.” – Binchy and Binchy

Dubai-based practice Binchy and Binchy, co-founded in 2016 by RIBA-accredited architect Ms Jennie Binchy(above), and known for its culturally-sensitive yet contemporary work, has recently designed a secluded desert artist retreat in Dubai. The building is located 3km from the nearest public road from the rear side of the site. The views from remaining three sides of the residence offers an uninterrupted desert-scape for miles. A faint outline of the iconic Dubai skyline can be seen on the horizon.

The brief was to design a series of prefabricated, interlocking structures, creating a semi-permanent desert retreat. The pavilion will be inhabited from time to time, and houses a VIP client and a series of resident artists and writers. The owner and the artists will collaborate together on the client’s upcoming projects.

As a place of design, the building is a visible expression of structure and honest detailing, both inside and out. “We spent a lot of time analysing prefabricated structures and their resonance with their own place of context, from Charles & Ray Eames’ House, Frost and Wexler’s Mid-Century prefabricated buildings in the USA, and Glen Murcutt’s identifiably Australian aesthetic,” shares Ms Binchy. “A barrel vaulted structure was also chosen to give this retreat a sense of place. Located in Dubai, the pure semi-circle arch form is synonymous with the region.

The linear plan is made up of a series of perpendicular, double and single height volumes. The client’s wing and the artist’s apartment are separated by a shaded outdoor dining space and outdoor kitchen. A sunken seating area and fire pit to the west of the pavilion is a place to savour the peace and quiet of the evening sunset.

The lofty rooms enjoy uninterrupted dual-aspect views, and catch the prevailing desert breeze. Bedrooms and bath tubs are located next to large openable windows and sliding privacy screens, connecting with nature and a feeling of outdoor living and bathing.

Reflection pools cool the air around the art and writing studios at the northern front, and a strike of lush greenery separates the pavilion’s rear entrances and service road. As a building of experience and interaction, this artist’s sanctuary is a place to enhance the creative process and to experiment with a new type of experience between work and life.

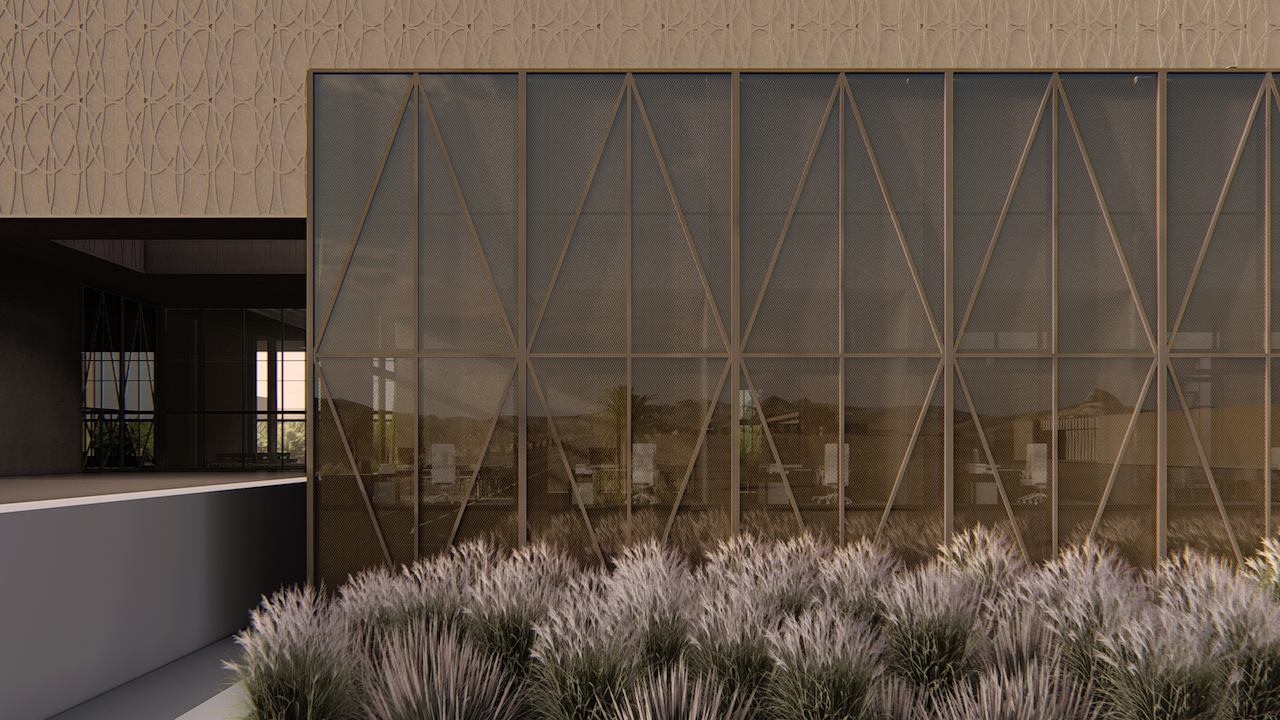

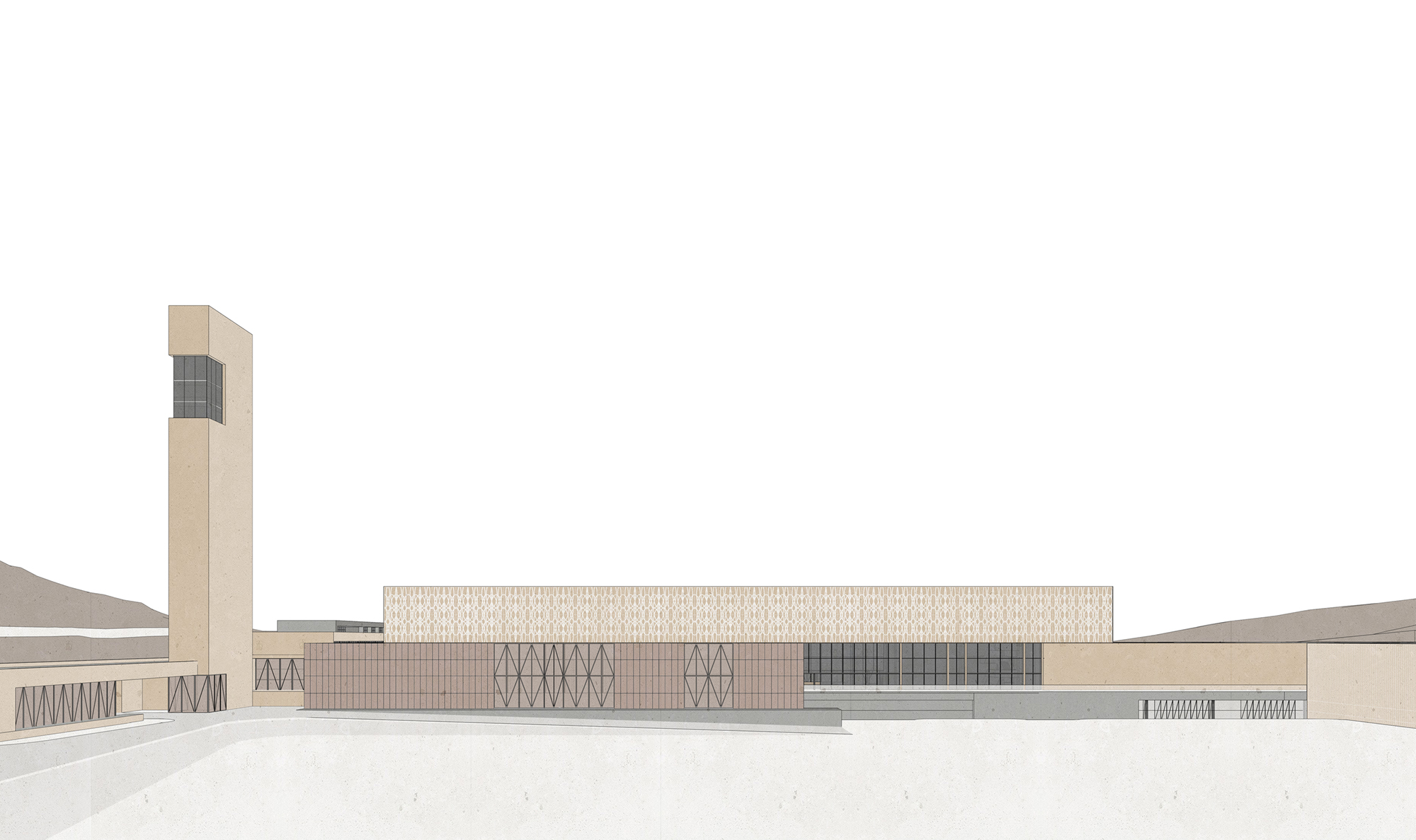

Another project that the firm has recently completed is the Police Training Centre in Oman that is also set in an arid landscape.

It take inspiration from the mountainous and dry environment of Oman, the surrounding grey mountains and rock formations, and the chiseled carved aesthetic of traditional buildings within this landscape. “We created an aesthetic language that reflects heritage and modernity in Oman, and also meets the advanced security and technical requirements of the project,” shares Ms Binchy.

A geometrically complex, yet utilitarian building, its solid facade maintains security and privacy and spatially designed around several lush internal courtyards. This project will house indoor and outdoor live fire training facilities, offices, lecture rooms, a gym, a restaurant, VIP areas as well as workshops and maintenance facilities, on site staff accommodation.

The project is extensive, over 100,000m2, and is low lying throughout. The complex is spread over several split levels that work with the natural mountainous landscape and avoid unnecessary excavation. Ms Binchy shares her firm’s take on sustainable designing in the desert environment.

What is your approach while designing in the desert?

As architects, we often feel that building in nature is a bad thing. But this is not always the case. By designing sensitively and working in harmony with the surrounding context we can create buildings that can have a positive impact on their environment.

Analysing and working with the site, its context and climate, is the fundamental basis for any design; the desert and other arid environments are no exception.

Taking cues from local vernacular architecture is a primary consideration for us. Rather than importing architectural styles, it is important to learn from the surrounding environment. Traditional sustainable solutions are often beautiful, and usually simple and cost effective.

The architecture for our training centre in Oman is predominantly made up of a series of solid facades which open up to courtyards, a traditional architectural feature of the region. The courtyards offer security and privacy as well as shade and ventilation. But more than this, these courtyards create comfortable microclimates for wildlife to live and thrive, which in turn offers a calm haven for the building’s users to enjoy.

In designing this serene and ‘inward-looking architecture’ we orientated most of the rooms and glazing around the courtyards. By day, this prevents birds from hitting the reflective glass (often a problem with skyscrapers) and by night this minimises the spill of light and sound pollution across the landscape that affects nocturnal animals and confuses birds as they fly. Once the sun sets, on the outside, the building mass becomes dark and one with the stillness of the night.

We have incorporated mashrabiya screens, another traditional feature, on both of our desert projects. We see these screens less as applied decoration, and more as a functional and significant part of the building’s architectural form. Where we are required to incorporate exterior facing windows on the training centre, full-height mesh screens supported by cross bracing, cover the glazing. In the desert retreat, mashrabiya screens are located at first floor level. The screens in both projects reduce the issues of glass reflection and assist with shading and cooling during the day. At night and during the winter, the windows can be opened allowing cross ventilation while maintaining privacy.

Reviewing masterplans and analysing future developments is also a key factor. Designing on arid ground is a little like having a sponge for a site. Porous surfaces are not static. The past and the future have great influence over a desert site, particularly in its relationship to water.

Climatic conditions such as heavy rains and flash flooding or a rising water table also need to be considered carefully. Water can travel very quickly and with devastating effects both above and below the ground, and in both remote and urban areas, so it is important to consider the wider context and future construction projects. For example, a significant study is now being undertaken to determine the effects of the new training centre in relation to the current flood management scheme. This also needs to take into account the masterplan for future development in the surrounding area which was established decades ago to make sure the water diverted from our site has somewhere safe to go.

Let me provide an example: In the past, I took over the design of a building and soon after it was finished, the water table rose significantly and began to fill the sump pump in the basement. Although it had not rained for months, it was some time before we could figure out the the root cause of the problem. The water was coming from the irrigation of a new golf course development two kilometers away. The infrastructure and housing in between the golf course and our plot was yet to be constructed and the water simply travelled to its lowest point which happened to be our building.

Can designing in the desert be sustainable while keeping its intervention low? How can this be achieved?

The artist retreat we have designed is intended to be temporary and reused later in another location. The prefabricated structure is also designed to minimise construction work in the area. The ground floor is raised on short concrete pad footings, so the building has minimum impact on the ground and services are also contained and removable.

This is the least intervention a building can have on a landscape, but the training centre is the exact opposite. As a solid and permanent intervention there is a lot we are doing to ensure the project is sustainable. It is the client’s intention that the entire project is self-sufficient in terms of energy use. This is another study that is currently ongoing, with reviews into solar power and alternative forms of renewable energy. The project also houses a mass garbage separation and recycling plant as well as all support services on site minimising transportation to and from the remote location.

How much does the scale of the project matter and how does it impact the sustainability?

As architects we have a responsibility in shaping our built environment to design intelligently and thoughtfully. I think that large or small, all good design is sustainable – it is about spending your carbon capital well as architects. Every building needs to be flexible and adaptable, where technology and its implementation can change over time.

A building that is built to high quality and designed within its environmental context, where the spaces are a pleasure to inhabit, is a building designed to stand the test of time. A timeless design will form a legacy for generations to come that will far outweigh the energy used to build it.

You might also like:

Aidia Studio to design 25 luxury pods with collapsible shells in Abu Dhabi’s Empty Quarter desert

A Day In The Life Of: Jonathan Ashmore

Dubai’s X-Architects wins competition to design luxury desert resort in Saudi Arabia’s Empty Quarter

Al-Ula Desert visitor centre by KWY Studio ushers new tourism era in Saudi Arabia