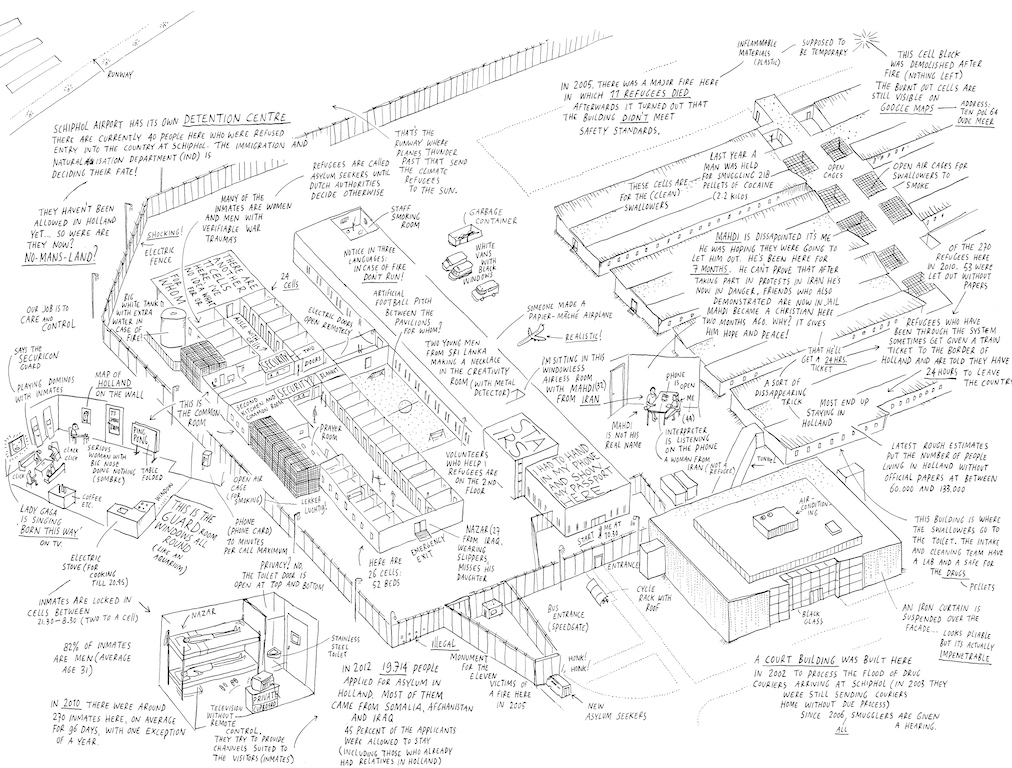

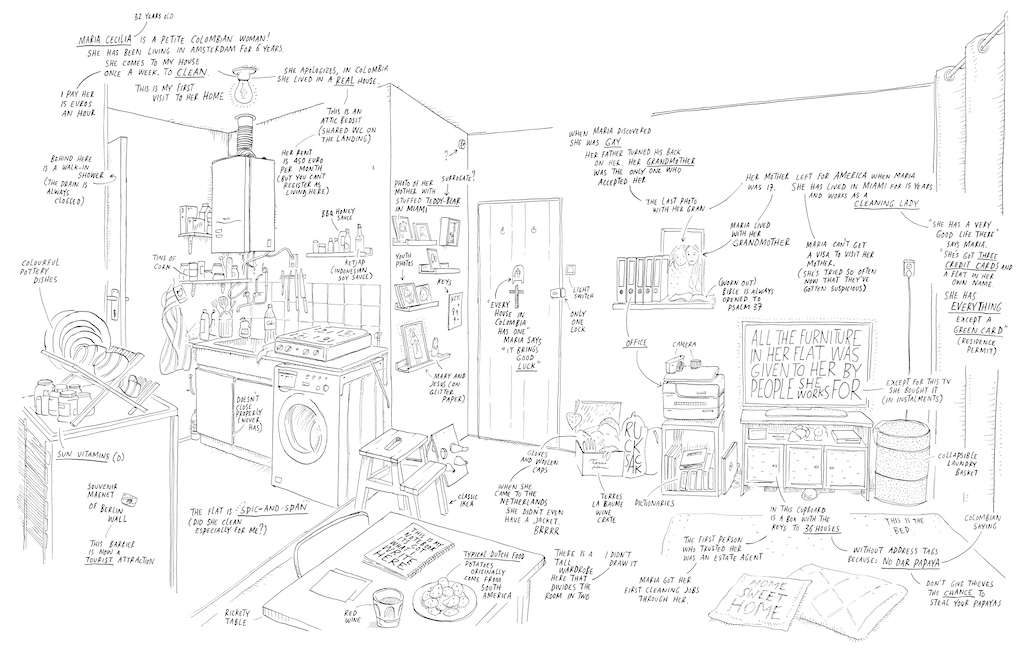

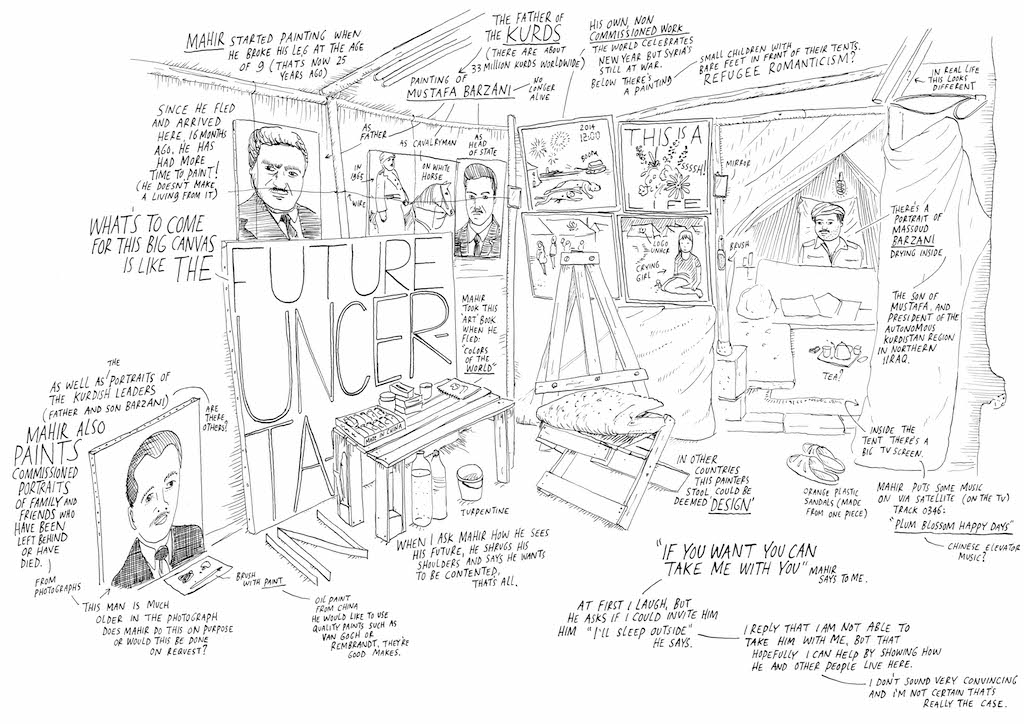

Dutch visual artist Jan Rothuizen documents reality in a way that is almost animated. His detailed drawings and nuanced descriptions of his surroundings draw upon his astute observations of real-life settings and tell in-depth stories behind the illustrations, often depicting cities, neighbourhoods, and houses. His work reflects on how we process information in this digital age – non-linear and multi-layered. Some of the places he has visited to document scenes include a warzone in Afghanistan, a detention centre for illegal immigrants at Schipol Airport, crisis shelter in a former bomb-manufacturing factory that now houses refugees, and a refugee camp on the Iraq-Syria border.

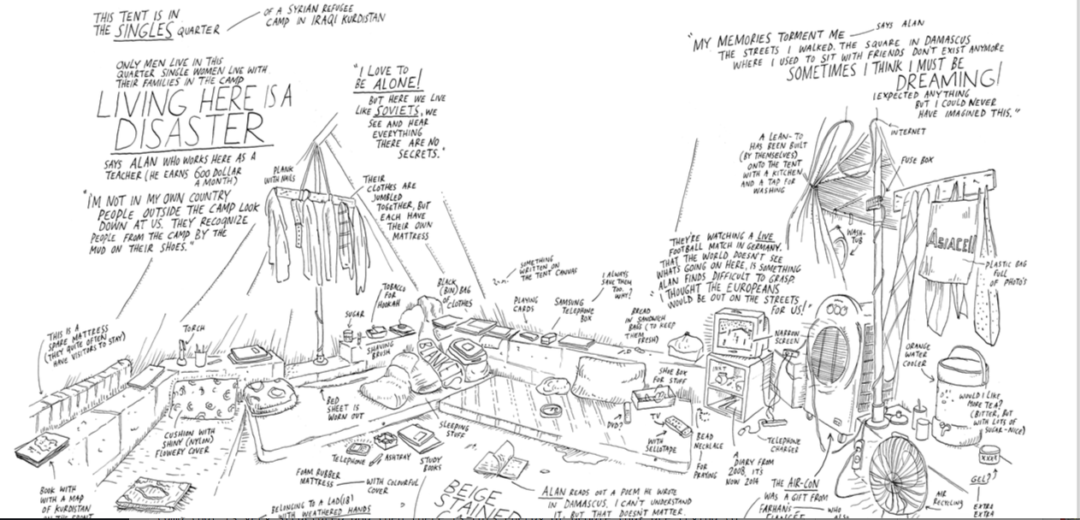

To mark the annual UN World Refugee Day on June 20, Amsterdam-based artist Rothuizen shares his observations with DE51GN on the refugee camp in Domiz in northern Iraq, located around 60kms from the Syrian border, and what comes across is the existence of a parallel world within the ongoing turmoil.

THE TRIP TO DOMIZ

The pictures of refugees, so far in Western Europe, have always been represented as very poor helpless people. I have a big interest in cities and I felt the need to go have a look at the refugee camps – not to look at them as a place of desperation that needs help but as an emerging city, and to get a perspective beyond the image that I was shown through NGOs. While the political aspect will always remain associated with refugee camps, but I wanted to look at the practical dimensions of these spaces. Although it’s the most common perception but I didn’t think too much about the risk in travelling there.

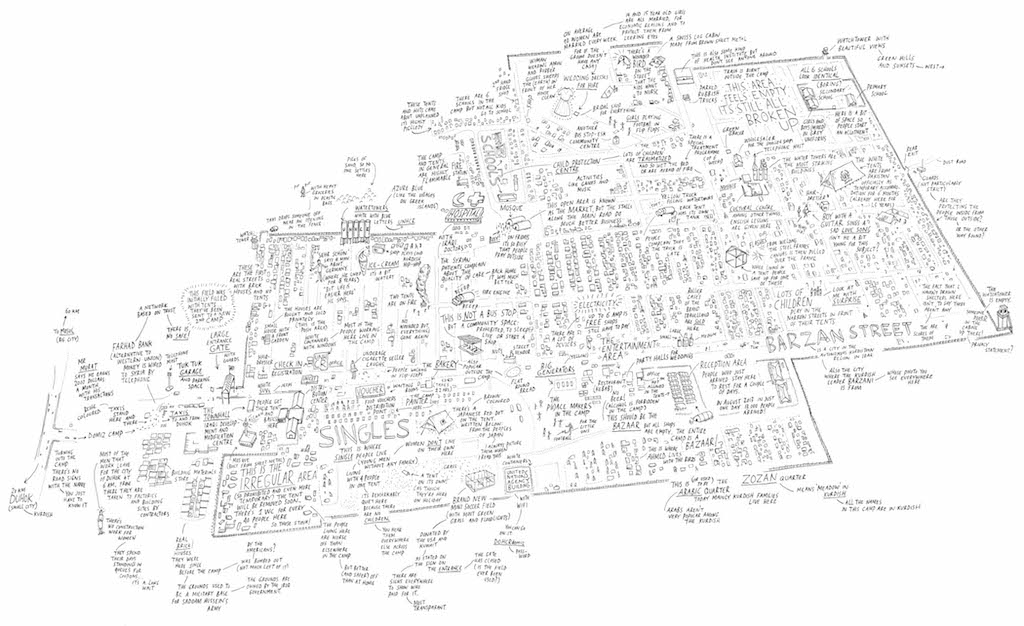

A PARALLEL ECONOMY

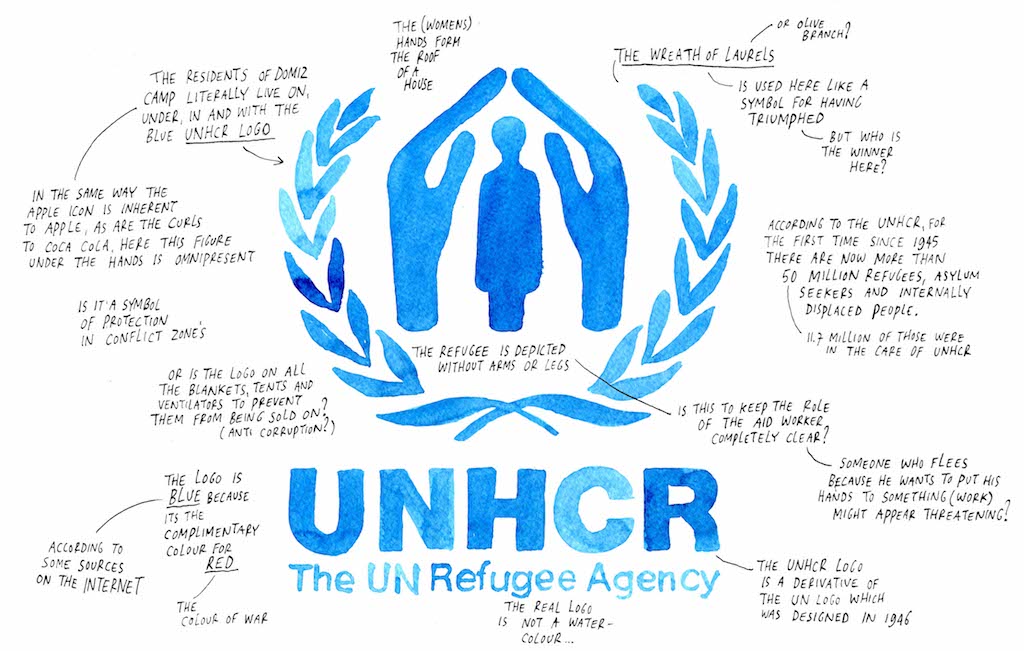

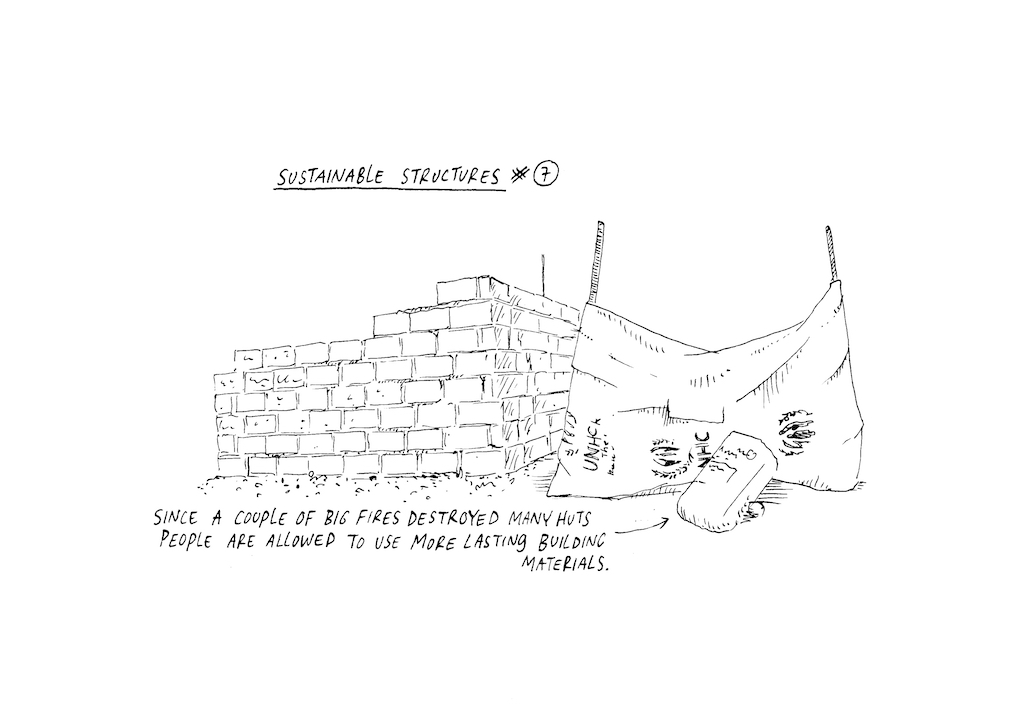

I was astonished and impressed by the informal economy in the camp. United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) has a plan to build camps that are very structured, but then there is this group of energetic people that are trying to build a life for themselves. There’s always some friction between the planned camp and the actual city that grows organically. That impression has stayed with me. I thought it was very interesting.

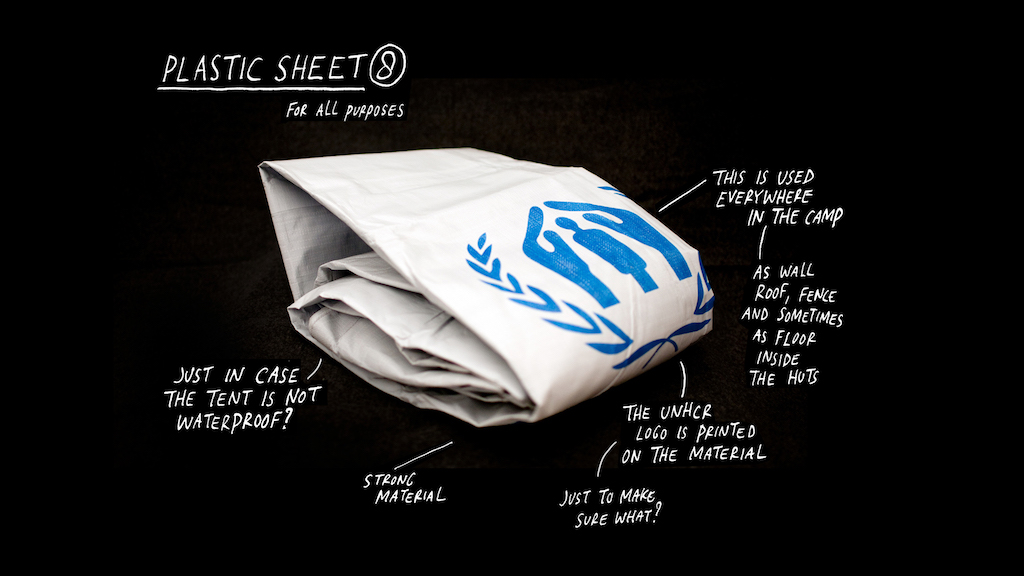

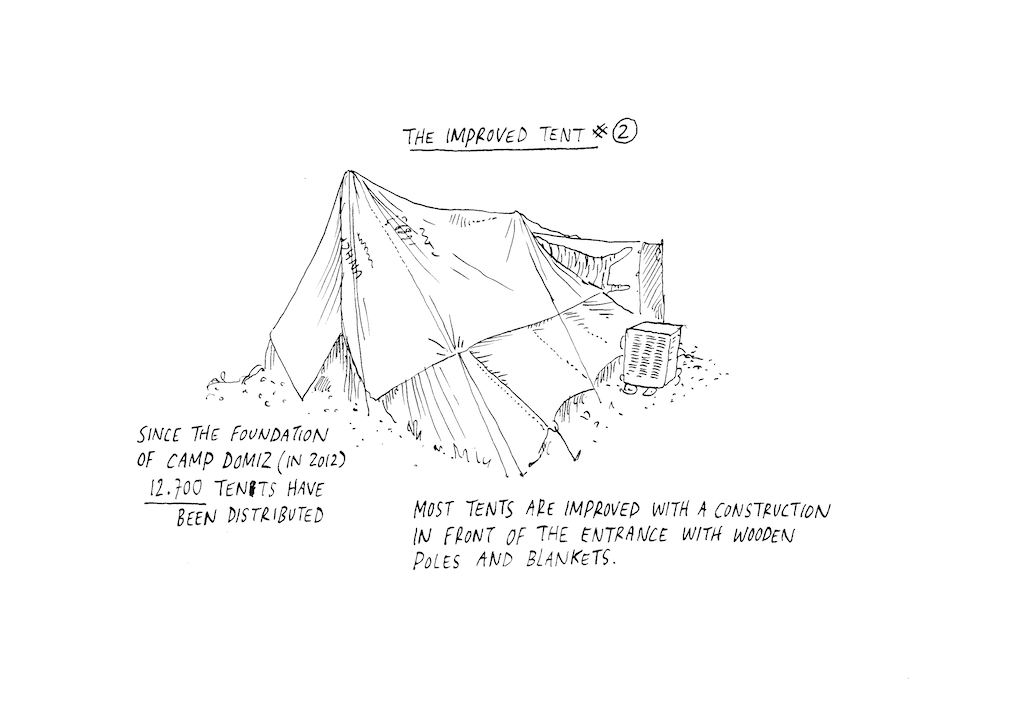

The plan might be to have a market street somewhere but that is where the people always pass by. The difficulty is that there are political challenges at play. Lots of countries want to help the refugees but they are also afraid that they’ll create a situation where people will become comfortable and won’t leave. For example, the average duration that refugees live in these camps is around 15 to 16 years. The first immediate help we give the refugees is a tent which probably lasts around three months at best. The way we approach the refugee crisis is from the Second World War – it’s like the ’50s mindset.

PARADOX WITHIN THE CAMPS

What you see is that NGOs try to engage people who live in these settlements. They recruit people from within. It is a wise thing to do but comes with its own challenges. If I talk specifically about the Domiz camp, it’s mainly a Kurdish camp, so the refugees still felt they were on their own ground but I can imagine when refugees in Calais camp in France try to cross the border to get into the UK, it’s a very different situation. People don’t live there to stay. There are many different aspects and every camp has different problems and possibilities.

It’s almost paradoxical that the shelters are temporary but at the same time the NGOs attempt to make them adaptable so there is room to grow and they can stay there comfortably for a long time.

You create a bubble world in these refugee camps but there are also many things that are not allowed in these camps such as people who prosper inside them. For example, a shop selling building materials in Domiz was moved outside of the camp, where a small economy was blossoming like a small town. They were not allowed to build a mosque inside the camp, so there was a mosque was built just outside the border. There many such frictions. If you think of it, UNHCR operates almost like a city-state with a set of strict rules.

“I made a drawing of the UNHCR logo and it explains the symbolism. The refugee is represented as a helpless person without arms and legs – it’s a very strong image that you find in all the camps and materials but it can also stigmatise them by making them anonymous.” – Jan Rothuizen

ASSIMILATION INTO HOST CITIES

In northern Iraq, where the camps are much older, you could see that some camps are really assimilated into the country. They have become like villages. There is also proven research that these camps often prosper and grow the economy in these areas. You can’t talk about camps in general. You have to look at these camps individually as each one has different dynamics. The problem with UNHCR protocol about camps is that there are so many refugees with different needs and different people that it’s difficult to say that they’re the same and have the same problems. It’s not like one formula fits all. NGOs actually do great work in these camps with schooling, hygiene, and wi-fi accessibility. The camps that I have visited have been very well equipped and run.

STRONGEST IMPRESSION

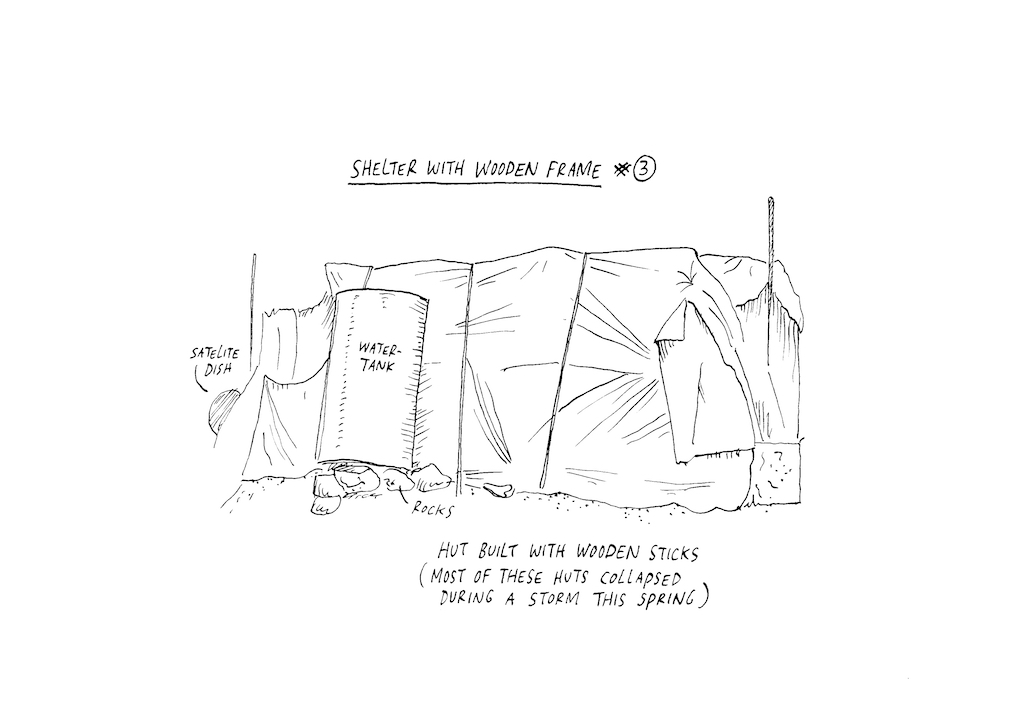

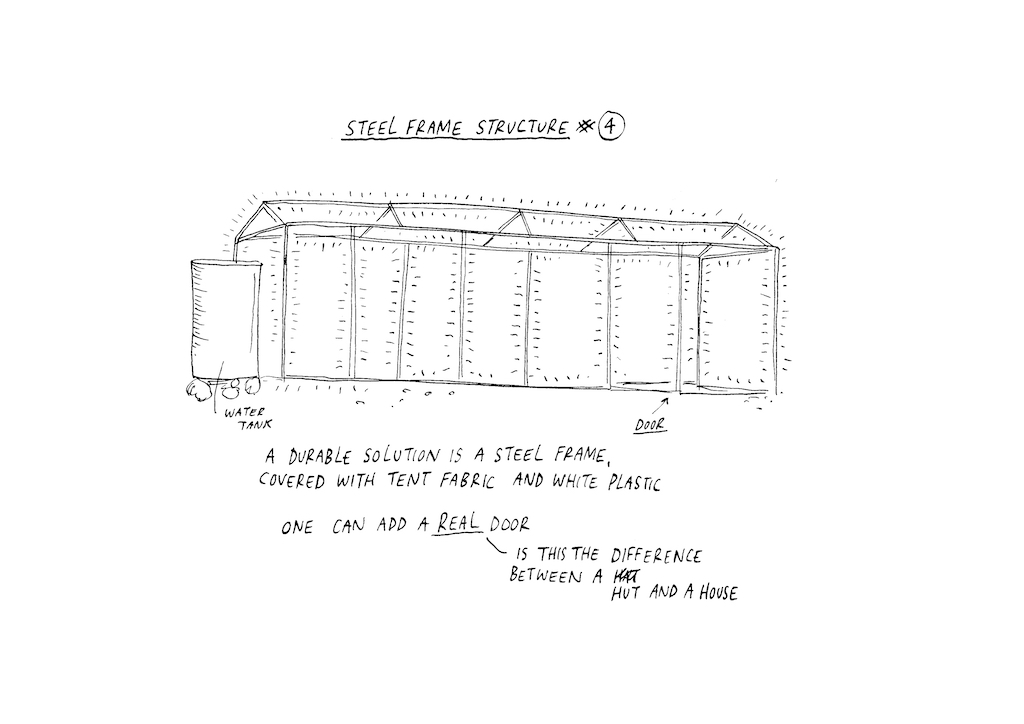

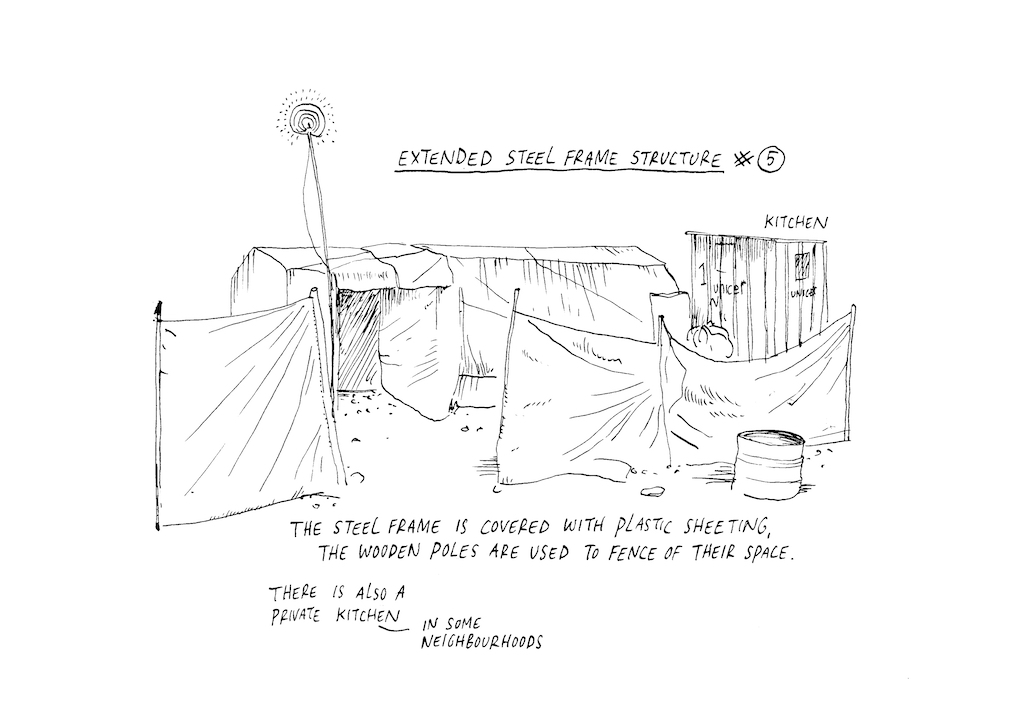

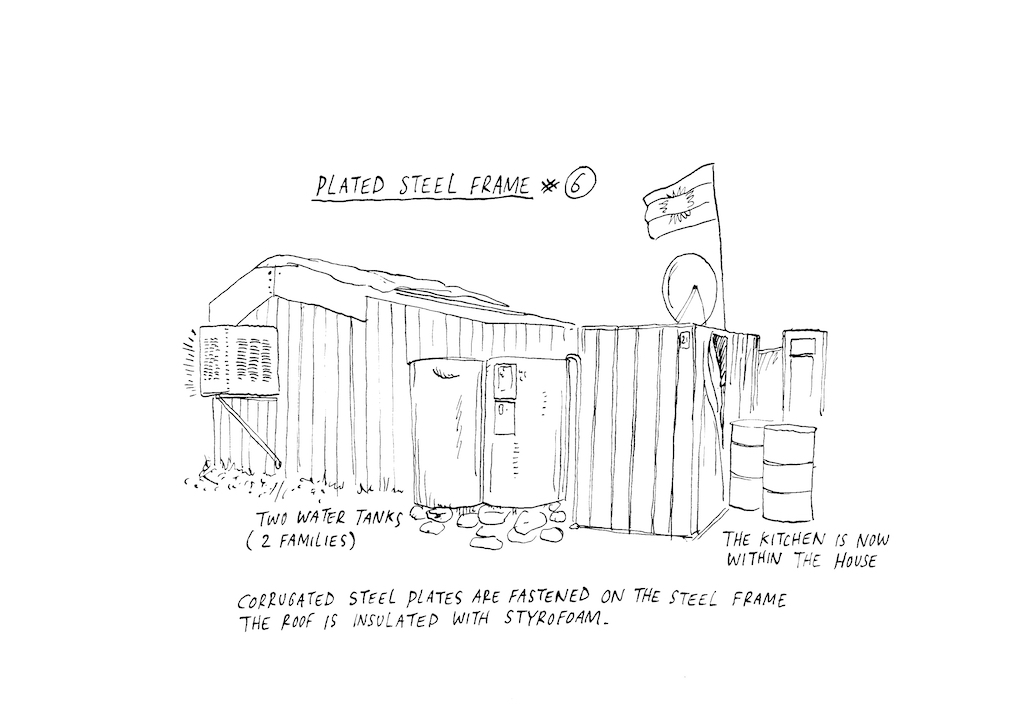

It has to do with my attempt to try and understand what it means to live in a refugee camp. There are these watchtowers on the edge of the Domiz camp and I observed that the watchtowers were empty and there was no one there. People used these watchtowers as toilets. It became obvious that there is a lack of privacy to even go to the toilet. Another thing I observed was that people were building an iron frame and they were putting the tent fabric on it and I never understood why they needed this frame until I finally realised that the most important thing for people is to have a door and lock it behind them. I felt these are things that matter a lot to people.

Think of yourself that is not your own, for example, a hotel room in a place where you’ve never been before among people you don’t know. You’d like to close the door behind you before you sleep. It’s a very basic necessity.”

The biggest problem is that people are in these camps for a long time with uncertainties. I have seen this even when people come to Holland before they know what their future is. The biggest problem is insecurity and they stay in a state of limbo. It’s the most difficult point in the whole process – provide a framework about their future. Not knowing what the future holds can be very devastating.

THE VARIOUS STAGES OF A REFUGEE SHELTER:

All images courtesy: Jan Rothuizen

You might also like:

Interview: Rizvi Hassan discusses Bangladesh’s social architecture that gives hope to refugees