American architect Paul Rudolph is one of the most celebrated figures of modernist architecture of the ’60s and ’70s. Evidently influenced by the works of fellow American architects Frank Lloyd Wright and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and their French counterpart, Le Corbusier, Rudolph went on to establish himself as a sought after architect not just in his native US but also in Asia. After graduating from the Harvard Graduate School of Design in 1941 and working under Walter Gropius, Rudolph did a stint in the US Navy between 1943 and 1946, after which he returned to the Harvard in 1947 to pursue his master’s in architecture, and finally launched his own practice in 1951. Most of his early commissions were houses and guesthouses in the southern states.

Concourse by Paul Rudolph, Singapore, is a 45-storey tower containing offices below and residential units above. Constructed, like all four of his Southeast Asia projects, of reinforced concrete, the complex is sheathed in ceramic tile to protect the concrete from humidity. The entire complex is characterised by the use of dynamic asymmetry. Rudolph has described the complex as a “whirling dervish.” Photo: De51gn

Things took an upturn when Rudolph was invited to design the United States Embassy in Amman, Jordan, which was not built, but two others – an office building for Blue Cross-Blue Shield in Boston and the Jewett Arts Center for Wellesley College – were completed.

After being appointed as chairman of the School of Architecture at Yale University, Rudolph went on to receive high profile commissions in Southeast Asia even as he was sidelined by major clients in the US. Even as some of his iconic buildings such as the Boston Government Service Center in the US attempt to stave off redevelopment bids, the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation – a non-profit organisation and custodian of the Paul Rudolph Estate – keeps his legacy alive through other initiatives.

We speak to Kelvin Dickinson, President of the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation about these initiatives which include the launch of the limited edition Rolling Chair designed by the late architect.

When was the Rolling chair designed and what was the inspiration behind it?

Paul Rudolph designed the Rolling Chair for his own apartment around the mid-1970s. He found a modular system of tubes and joints that was used for retail store displays and liked the modularity of it because he was experimenting with some of the same principles in his architectural projects. Rudolph was influenced by the work of Rietveld but he used materials that he was interested in – in this case, plexiglas, chrome and metal casters.

Which other furniture pieces did Paul Rudolph design?

Rudolph, like other architects such as Frank Lloyd Wright, was interested in designing total environments, and not just the architecture. In that spirit, he often designed custom pieces for his clients, especially when it was a private residence. He designed free-standing tables and chairs for many of his residential projects in addition to built-in pieces.

“With a few notable exceptions, most of his work during the last 20 years of his career was in Asia. We are still – 22 years after he passed away – discovering projects in places like Singapore that we did know existed because Rudolph was too busy to update his office project list.” – Kelvin Dickinson, President, Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation

Please share some of the ongoing initiatives at the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation?

The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation is dedicated to communicating, preserving and extending the legacy of architect Paul Rudolph. We do this through opening our Paul Rudolph-designed headquarters to students and the public so they can learn about his work through direct experience. We advocate for preserving his built work, of which three projects are currently threatened with demolition. We are developing an archive of his work and making it available online to students and researchers. We are also supporting a publication about his work and are planning an exhibition this year featuring some of his residential projects.

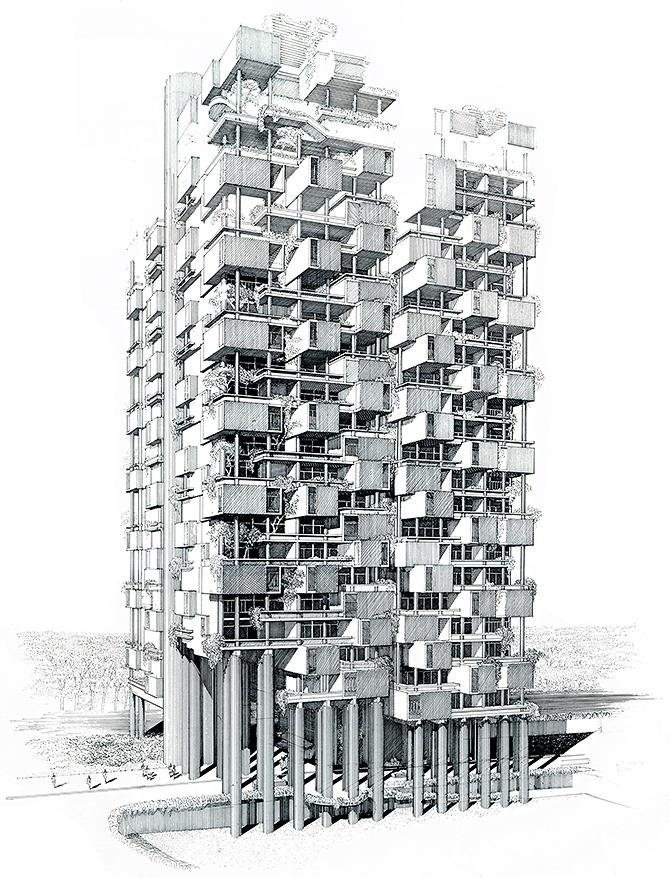

Colonnade, Singapore. Commissioned by a Chinese family, the building is again made of reinforced concrete but here it is protected by masonry paint. The Grange Road building is divided into four quadrants each beginning and ending at a different elevation. The most striking visual feature of the exterior of Grange Road is a series of projecting blocks cantilevered well forward of the structural columns.

How does Asia contribute to Paul Rudolph’s architecture legacy?

Rudolph’s reputation suffered in the United States due to a change in taste towards Postmodernism and an unfortunate fire at the Yale Art & Architecture building in the late 1960s. A decade later, be began to get commissions for projects in Asia and his career essentially was reborn overseas. With a few notable exceptions, most of his work during the last 20 years of his career was in Asia. While his early work in Florida and larger projects at the height of his career are well known, it is his work in Asia that has yet to be fully explored. Rudolph was at the peak of his creativity during this period. We are still – 22 years after he passed away – discovering projects in places like Singapore that we did know existed because Rudolph was too busy to update his office project list.

Bond Centre, Hong Kong. In a sharp departure from his usual practice with concrete buildings, Rudolph chose to cover the two structures completely with a curtain wall of painted aluminum and grey glass.

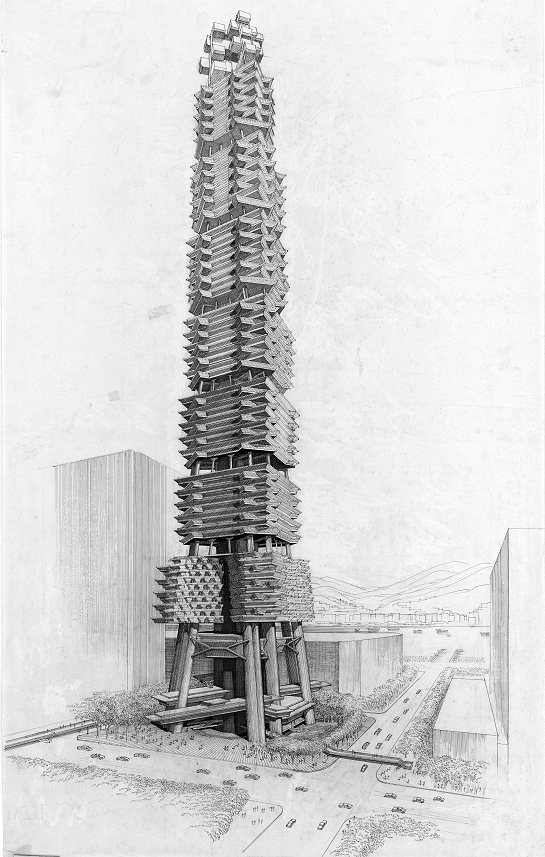

Wisma Dharmala, Jakarta, Indonesia. It exhibits the same kind of swirling geometry seen at Singapore’s Concourse. Wrapped around an open courtyard is a podium containing a garage, exhibition space, and a bank. Spiralling up from the outdoor area and podium, the floors of the office tower, each with its wide overhangs, rotate around the structural columns creating a complex interweaving. e terrace parapets, was based on roof forms found in indigenous houses in Indonesian villages. Reinterpreted in reinforced concrete, the overhangs shield the glass walls of the office below from the sun.

Which of his works in Asia, if any, were the closest to his heart and or which among them exemplify his design philosophy?

While Rudolph poured all of his design skills into every project, there are a few that were considered special. The Dharmala Sakti building in Jakarta, Indonesia is still held up as an early example of green building principles and reflected Rudolph’s concerns of regionalism in modernist architecture. The Colonnade in Singapore explores Rudolph’s interest in modularity and interlocking spaces, while the Bond (now Lippo) Centre in Hong Kong reflected Rudolph’s concern about how to apply scale in the design of tall buildings.

All the building images, unless otherwise stated, are courtesy © The Estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation.