Anjali Mangalgiri is the founder and principal architect at Grounded, an award-winning architecture and development firm that she founded in 2010. After graduating with a Bachelor of Architecture degree from the School of Planning and Architecture (SPA), New Delhi in 2002, Mangalgiri moved to the US to do a Master’s in City Planning from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). In 2005, she joined the global architecture practice HOK in New York, where she worked on urban planning projects before returning to university to complete a Masters in Real Estate Development at Columbia University in 2008.

While in the US, Mangalgiri missed the hands-on practice of design that was directly influenced by the earth and soil- a practice that had left a deep impression on her during her architectural internship in Auroville where she built using earth, straw and other sustainable materials.

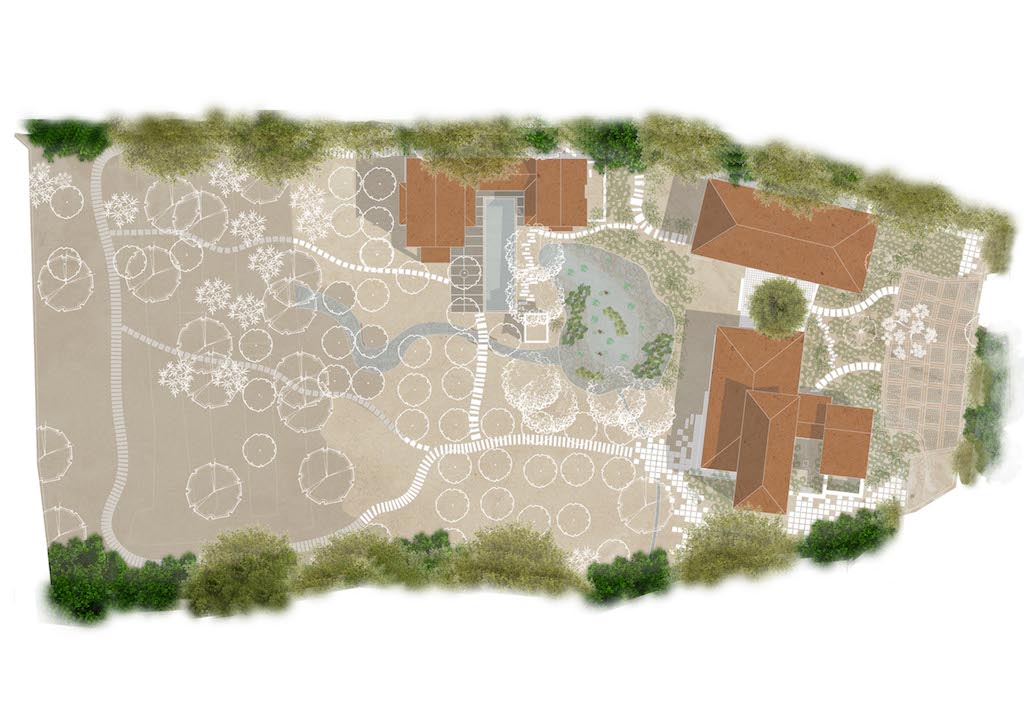

The Navovado House in Goa by Grounded has received critical acclaim for a respectful response towards its context.

The idea of bringing forth this tactile experience together with the broader knowledge on planning, policy and business that she had gained in the US, led Mangalgiri to set up Grounded, her own practice in Goa, India in 2010. As one of the few Indian female principal architects under the age of 40, leading her own architectural practice, she is conscious of the need to give back to the industry by way of mentorship opportunities.

Besides having won several industry awards, she has been a TEDx speaker and her work has been published in global publications. She is an amateur potter, an aspiring gardener and on the personal front, as a mother of two girls, she is keen to talk about the challenges and pressures faced by new mothers who choose to return to work soon after giving birth. She currently resides in Singapore with her family, but divides time between Singapore, Goa and New York for work. DE51GN speaks to Anjali Mangalgiri about her contextual work underscored by sustainability.

When did you move to Singapore?

I started my practice in Goa in India in 2010, while my husband continued to live in New York. At that time, I was splitting my time between Goa and NYC. My husband moved to Singapore in 2012, and I started to spend time between India and Singapore. I have been spending more time in Singapore since 2015, when I gave birth to the older of my two daughters.

Your practice is based in both Singapore and Goa. What are the primary differences and similarities if any? Is it driven more by heritage and vernacular methodology in Goa?

Most of my projects continue to be located in the Goa and Mumbai region. The workflow in India has kept me pretty busy and honestly, I have not had time for expansion. Our projects also tend to be quite large and we work on almost all aspects from architecture to interiors and landscape. I have a small design team in Singapore where we focus on design concepts and preliminary design. My implementation team is located in Goa where they manage site work and working drawings. I make site visits on a monthly basis and we coordinate daily over skype.

All our projects are first and foremost, a response to the site and its context. The context can be from the surrounding architecture and many times from the site’s landscape, the existing trees, water flow patterns and views.

In Goa, one of our projects, Navovado was sited among old Goan homes (an adapted Portuguese style). To blend into this rural Goan landscape, we designed our front elevation at Navovado with a large sweeping roof using terracotta tiles that responded to the scale and materials found in the surrounding architecture. In another project, House with 3 Pavilions, the natural features of the site were the contextual start to the design. As the name suggests, the house is designed with three pavilions, and they are all based around a pre-existing natural pond. The main house and the guest annex pavilions are further connected through a courtyard that runs around a large existing fruit tree found on the site.

What are some of your recent projects, both in Singapore and Goa?

We have been quite busy for the past couple of years, working on two large houses, one in Goa and one outside of Mumbai. Both houses are spread over large rural tracts of land and range from 740m² to 929m² in built-up area. These homes are expansive with an emphasis on indoor-outdoor spaces, and feature luxury amenities such as swimming pools, jacuzzis, recreation rooms and spas.

Anjali Mangalgiri’s colonial era apartment in Singapore reflects her passion for preserving the natural details of a space.

In Singapore, I recently renovated my black and white apartment located in a colonial 100-year-old building. The apartment boasts of 12’ high ceilings and large expansive windows that are surrounded by huge historic trees. During the renovation, we tore down the walls between the kitchen and living to create a large open plan living space, a dream space for most architects. A large island with a wood counter was added in the centre to enhance the flow of space between the spaces. The resulting space has a raw loft-like feel, with abundant light and breeze that I love. The space offers a place for me to display my art and my favourite interior objects like the Saur wood dining table from Indonesia, rice paper lamp above the dining table from my favorite Goan designer, an antique Indian door converted into a mirror, another full-length mirror made from reclaimed wood, hand-embroidered ‘Suzani’ textile from Uzbekistan and big ceramic lamps from Vietnam.

How would you define your style?

With an emphasis on designing for the tropics, our design style is predominantly ‘Tropical Modern’. We borrow architectural elements and materials from local buildings that typically respond to the local climate and are locally produced using local craftsmen and raw materials. Our design aesthetic is rustic yet contemporary. We want our buildings to belong to the land and to the current time. The site’s landscape takes centre stage in our architecture. As a policy, we do not cut any trees for the building construction, and the natural features at the site are always the starting point in our design process.

We have a strong commitment to building sustainably and responsibly, such that the buildings become a part of the landscape rather than an imposition, an object or a statement. It is our policy to get green certification for all our projects. Our project Nivim, was the first green-certified home in the state of Goa in India.

How does materiality and contextual building influence your work?

The site’s context – in the form of the surrounding architecture or natural features – is the starting point in our design process. The choice of materials also plays a big role in the process. It is very important for me that my buildings blend into the landscape. In Goa, for instance, we use a lot of local stone for external walls, and flooring. We also prefer to use the local terracotta clay roof tiles that mirror the red earth found in the region. I find that these roofs tie the buildings further to the surrounding landscape and visually reduce the scale of the buildings to blend into the landscape. Finally, our choice of materials is heavily dependent on the sustainability criterion. We tend to prefer local materials, and those with high recycled content.

Which are your favourite buildings in Singapore and why?

I am always impressed by Singapore’s talent to refurbish and adaptively reuse old buildings. My favourite building in Singapore has to be the Singapore National Gallery. Its refurbishment and conservation are sophisticated and modern, yet it is non-obtrusive to the historic character of the building.

Another building that I admire is the National Design Center (NDC). I spent some time in the building when I curated an exhibition for the Singapore Design Week in 2018. I love the simplicity of the modern intervention that really makes the building contemporary without losing its old-world charm. I only wish that the NDC would engage in more public programming of their wonderful space in the atrium and the courtyard. The building has a great connection to the street, something that is often missing in buildings in Singapore. And this can be really used to draw people in and to engage with design. That space has great energy but it is sadly missing some thoughtful programming and the design buzz. I hope for it to become more inclusive and welcoming through programming and site activations.

National Design Centre in the Bugis-Bras Basah Arts precinct is located in a conserved building, which was refurbished by SCDA Architects. Photo: Aaron Pocock

Heritage and colonial past have a huge bearing on Singapore and Goa’s architecture. While in Singapore, there is the Urban Redevelopment Authority that plays a big role in the conservation of heritage buildings, is there a similar body in India that looks into the maintenance and gazetting of historic buildings?

Absolutely, there are government departments within the Town and Country Planning office in Goa that look after the well-being of historic buildings. They are responsible for the listing of historic buildings in the state and the enforcement of government policy regarding the same. Goa actually has a few UNESCO World Heritage sites that are very well looked after, as they have access to generous funds and resources. There is a non-governmental body named Goa Heritage Action Group (GHAG) that is a citizen run advocacy group. I am a member of this group. It is a group of well-intentioned folks, who act like watchdogs for any wrong-doings or law breaking when it comes to the heritage buildings. They also disseminate information on the historic buildings of Goa by the way of books, heritage walks and talks.

Photos: Grounded

You might also like:

unTAG Architects designs low-impact and affordable luxury house for retired farmer in rural India

Villa in India by SquareWorks is built around verandah concept to keep away extreme heat