Singaporean architectural photographer and filmmaker Kevin Siyuan has recently completed a short film called Corridors of Diversity based on the city’s acclaimed public housing milieu. Having formally trained and worked as an urban planner, his work revolves around the built environment, emphasising on the nuanced interactions of various buildings against people through density, against natural elements through forms, as well as their surrounding environment through functions. His works have been nominated in numerous international awards, such as The Architectural Photography Awards (2017), International Garden Photographer of the Year (2016, 2017) and Art Olympia Japan (2017). They have also been exhibited internationally in more than 10 countries, in cities such as Singapore, New York, London, Tokyo, Berlin, Seoul, Budapest and Athens.

Background music credit: “Almost Flying” by Mattia Vlad Morleo / Artlist

In an interview with DE51GN, Kevin sheds light on the inspiration behind the short film and the significance of the diversity that thrives within the common spaces of Singapore’s Housing Development Board apartment blocks.

What inspired this project?

This short film is a continuation of the still image series that I have worked on for the past three years. It is a summary of my personal journey to document public housing corridors that endeavours to represent the urban image of Singapore. The project was inspired by many of the urban planning principles I learnt in school, such as the concept of land-use zoning, green spaces, urban and architectural design. I always wanted to produce something “artsy” that could portray these concepts visually, and then one day it all began by a chanced encounter when I took a photograph of a HDB corridor at Kreta Ayer that encapsulates the past, present and future of the surrounding cityscape. The artistic direction of the short film was influenced by Wes Anderson style of filmmaking.

What is the objective of this project?

The objective of the Corridors project is to infuse elements of Singapore’s urban planning and public housing and showcase it as an art form. While doing that, I could also document Singapore’s ever-changing built environment and preserve them as visual memories for keepsake.

We know that Singapore HDBs are a microcosm of cultures and communities. What new perspectives have you gained while working on it?

The corridors are definitely very interesting places filled with signs of life. During my trips to many of these corridors, I have found that the majority of the homes I came across have had some form of personalised usage of the corridor space outside their units. It could range from recreation (such as the keeping of plants, birds), bicycle storage, demonstration of religious beliefs, festive decorations to even stylish tables and chairs.

I can see that the residents are adding a personal touch to the corridor spaces, which really allows me to have a glimpse of their different ways of life and cultural beliefs without them actually being present. These personalised items make the corridor more of a secondary social and living space instead of simply a passage. In addition, I have also noticed that activities represented by these personalised items seem to reciprocate with the greater surrounding environments. For instance, there appeared to be more residents growing plants or doing gardening in HDB blocks near major parks and gardens, whereas there are also more households that displayed religious items in blocks with close proximity to places of worship. Such influences are really interesting especially when captured in photographs.

What were the most challenging and rewarding aspects of making this film?

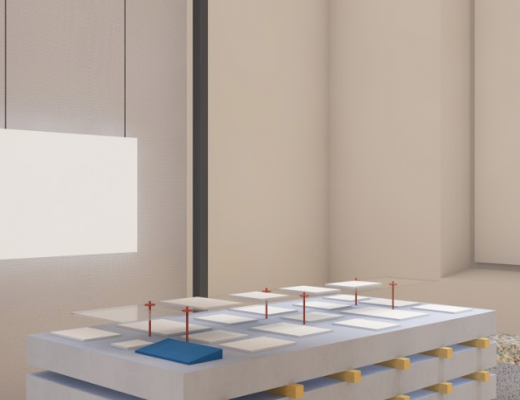

The actual filming process was definitely the most challenging part. The corridors are very confined setting for filming, so in order to compose and maintain the centre-divided view while moving (especially for the timelapse scenes), I would require a large degree of flexibility and precision. Commercial video cameras and even DSLRs are too bulky for that, so I decided to use a GoPro, a gimbal and a custom made dolly using Lego parts so that it was compact enough to move along the parapet wall smoothly. Obtaining all the necessary footages that tell the full story is no easy task either – I wanted this short film to be a representative showcase of Singapore’s public housing, so it comprises of a montage of 48 different scenes scattered around Singapore, I travelled all over Singapore for around half a year to produce these footages.

What is most rewarding is the actual journey undertaken to do the filming and photography. I came across corridors with breathtaking views, corridors with cosy atmosphere, corridors with different shapes and designs and corridors with rich cultural elements. I have discovered so many hidden gems all over Singapore and this is the most treasured takeaway for this project.

You are an architectural photographer. How would you describe the role of HDBs in the context of Singapore’s architecture?

I would say the HDBs are the defining feature of Singapore’s modern architecture. In terms of building form, I believe that the HDBs are the true visual landmarks that characterise the urban image of Singapore’s built environment. They are ubiquitous, be it in the heartlands or right in the heart of the city. They are also irreplaceable, as a physical element that is uniquely Singapore, their collective presence could shape the imageable skyline of Singapore. In terms of functions, they also played a crucial role in providing housing and homeownership to over 80% of the country’s resident population, a feat no other public/social housing programmes all over the world have attained.

A few years ago, there was a documentary on the void decks and how they support a lot of different programmes as a community space – from play areas to hangouts, wedding venues, and even wakes. Do you observe similar phenomenon – community gathering – in corridor spaces as well?

Both are spaces that facilitate social interaction and foster community spirit in my point of view, although there are some subtle differences in the functions. The void deck, when utilised, serves primarily as an event space where a planned event (say wedding) occurs during a particular period in time. Corridors, due to its designs are essentially secondary territories, or “bridges” that literally connect you and your neighbours. There will be social interactions but most of them should be chanced encounters, that may foster a permanent connection in the long term.

While working on this documentary, did you make any comparisons between the old HDB typology and the new style of HDBs? How are they different and/or similar?

All of the footages for the short film are shot at blocks with older typology (eg. slab blocks with long stretches of corridors built before 2000). This is more of a project requirement as this is the only typology where the centre-divide composition could work, and a balance of common corridor against the greater built environment could be achieved.

In terms of their design attributes, both the old and new styles have their own merits. The newer flats (such as the more recent point block flats, Pinnacle@Duxton, Skyville@Dawson and flats in Punggol and so on) certainly have more distinctive exterior designs, with greater density and spatial efficiency and improved facilities. Residents also enjoy more privacy. There are also new type of spaces (such as rooftop gardens) that enhance liveability. On the other hand, older flats are more open in design, with greater exposure to natural lighting in communal areas, and of course greater amount of accessible secondary territories. These spaces with ambiguous use bring the human dimension out of the boundaries of individual units, and the spillover makes the flat and the neighbourhood feel more homely with a more distinctive character. Orderly chaos, you might say.

Which are some of your favourite buildings/structures in Singapore and why?

Pinnacle@Duxton – Design-wise this project is one of the most unique landmarks I have ever seen for public housing. But what I like the most would be its sky garden on 50th storey, which I enjoy visiting from time to time. The sky garden connects all seven blocks together, so it’s very spacious with a 360-degree view of the built landscape of Singapore downtown. It is a very comfortable place to enjoy an evening at, and it even serves as a great vantage point for me to photograph taller skyscrapers for some of my commercial assignments.

Raffles City – it is one of the three buildings designed by Mr I.M Pei in Singapore. I like both the form and function of this building. The building design is visually memorable, its aluminium and glass façade is strikingly dazzling under the sunlight, its changing and diverse geometrical elements makes the building special when viewed from different angles. It is very modernistic, yet it is also in harmony with its surroundings and does not look out of place. Functionally, it really is a “city within a city”. It’s a bustling mall yet does not appear to be crowded. The spacious interior and natural lighting elements and connectivity to surroundings makes the experience very enjoyable.

Marina Bay promenade – I’m referring to the stretch of waterfront public space outside of the Shoppes. The promenade has personal meanings to me as this is the place I visited the most when I just started to get into serious photography, so this is my “training ground” where I explored different concepts, be it photographing the skyscrapers across the bay, doing street photography by capturing pedestrians passing by or doing some abstract and minimalist shots by shooting reflections from the glass surface at the Shoppes – this place contributed so many ideas that laid the foundation of my photographic endeavour. I still visit here a lot nowadays because it’s such a vibrant space filled with new inspirations.

From a visual point of view, how would you describe Singapore’s architecture – both old and new?

Singapore’s built environment comprises a harmonious co-existence of past, present and future elements, and hence it has a great diversity in both forms and functions. Be it conservation, refurbishment and future development, everything has been well planned for and laid out through zoning, as a result, I feel that the overall architectural image has been neat, organised, but also vibrant and diverse with strong cultural elements. From the urban design perspective, there is a need for most buildings, old or new, to follow guidelines from structural design to even facade colour details in order to remain consistent with the overall image of its surrounding neighbourhood. Many old buildings, such as the shophouses and historic monuments with time and cultural roots are conserved and/or adaptively reused. Whereas there are also new buildings with modernistic design, sustainability considerations and good use of latest technology that are being added to the skyline. This blend of old and new makes the architecture really interesting. Perhaps one drawback of Singapore’s built environment is that it is changing a little too quickly. Not all old buildings can be preserved, and quite a number has already made way for new developments.

Any favourite architects living or dead whose work you admire? What’s special about it?

I.M Pei – I admire his “modernist localism” approach of designing globally recognisable architecture that is meaningful within the local context, as well as his mastery of geometry by creating forms that are visually stunning through the use of simple shapes.

Norman Foster – I admire his philosophy of using architecture as an expression of values, both symbolically and literally, so it adds meaning to the design. I am also a fan of his design style: polished, modern, simple yet magnificent, with great leverage on latest technology.

Liu Thai-Ker – As the “architect of modern Singapore”, he has made a great contribution to public housing and urban planning of Singapore, in particular the planning and development of many HDB new towns. As an urban planner, he tends to see the bigger picture and I particularly admire his appreciation of land in its original form, and his definition of good buildings as those in harmony with their neighbours.