At its 10th World Congress, the CTBUH network was approached with the question: “Which tall buildings completed in the last 50 years have profoundly enhanced the cities in which they are located and/or have greatly influenced the practice of designing tall buildings?” This led to the nomination of 50 buildings around the world. Here, we chronicle the most influential skyscrapers built in the Asian continent in the past half a decade. The list includes those in the Middle East, which technically lies within Asia.

Jardine House, Hong Kong, 1973

Designed by P&T Architects, this office tower became the tallest building in Asia upon completion, and held the title for seven years. The circular porthole-shaped windows are inspired by the nautical history of the city and the building’s site. It also formed a key node on the city’s growing skybridge network.

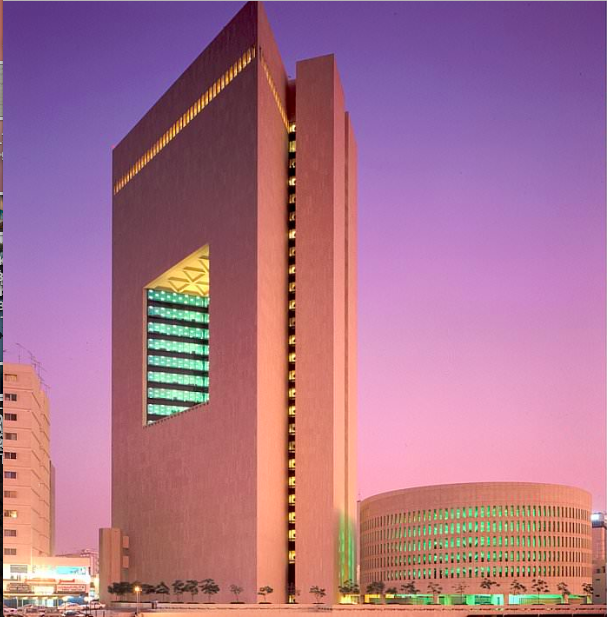

National Commercial Bank, Jeddah, 1983

This corporate headquarters by SOM, was Saudi Arabia’s tallest building for 17 years, and was one of the first tall buildings to adapt the specific vernacular techniques of local architecture in the Middle East. Office floors are clad with windows facing the courtyard, and solid walls of Roman travertine line the exterior, illuminating interior spaces with ambient sunlight, but eliminating heat gain from direct solar exposure.

Hong Kong and Shanghai Banking Corporation Headquarters, Hong Kong, 1985

The design of the HSBC Headquarters by Foster + Partners is much-emulated, as it achieved a unique harmony of public space, practical reconfigurability, and iconic city. Built on a compact site within a short span of time, it used plenty of prefabrication techniques. The open-space needs of the bank led to the placement of elevators, stairways and building services at the ends of the office floors. The floors were suspended between the cores and pairs of steel masts located at the ends of the building. A mirrored sun scoop reflects natural daylight into the atrium, and through a glass ceiling to an open-air public plaza below.

Bank of China Tower, Hong Kong, 1990

The Bank of China Tower by the late I.M. Pei, used a sophisticated exterior bracing system, using the form of bamboo shoots—as symbols of strength, growth, and prosperity—for inspiration. The whole structure is supported by five steel columns at the corners of the building, with the triangular frameworks transferring the weight of the structure onto these five columns. This innovative composite structural system not only resists high-velocity winds, but also realized significant savings in construction time and materials.

Petronas Towers, Kuala Lumpur, 1998

Designed by Cesar Pelli, The twin towers of Petronas held the crown of “world’s tallest building” for six years, raising the profile of Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia and Asia itself as an innovative region for skyscraper development. Spanning the gap between the towers, at an elevation of some 170 meters, a two-level skybridge can also be used as a means of escape to the neighboring tower should one tower become unsafe in an emergency.

Burj Al Arab, Dubai, 1999

The Burj Al Arab is regarded as one of the first key landmarks of modern Dubai. Inspired by the shape of a sailboat about to head into the Persian Gulf, the triangular building’s design by Atkins began with an intent to create a recognisable landmark for the emerging city. Upon completion, Burj Al Arab was the world’s tallest hotel and included the world’s tallest atrium, which rises 182 meters through the interior of the building.

Jin Mao Tower, Shanghai, 1999

The Jin Mao Tower by Adrian Smith, while he was at SOM, is an important building for Shanghai and China. Its setbacks and spire recall the skyscrapers of 1920s New York, while its stacked, stepping form resembles a pagoda, establishing it as a distinctly Chinese landmark. Its soaring interior atrium runs through the top third of the tower, providing a dramatic view from the hotel room corridor balconies.

TAIPEI 101, Taipei, 2004

Holding the World’s Tallest Building title from 2004 to 2010, TAIPEI 101, designed by C.Y. Lee and Partners, has become a global icon and set a worldwide precedent for sustainable skyscraper development. The tower rises from its base in a series of eight-story modules that flare outward, evoking the form of a Chinese pagoda. It features energy-efficient luminaries, custom lighting controls, low-flow water fixtures, and a smart energy management and control system. The building has become a central component of New Year’s celebrations, including a dazzling fireworks display.

Shanghai World Financial Center, Shanghai, 2008

The Shanghai World Financial Center, by Kohn Pedersen Fox, is a symbol of commerce and culture that speaks to the city’s emergence as a global capital. Shaped by the intersection of two sweeping arcs and a square prism—shapes representing ancient Chinese symbols of heaven and earth, respectively—the tower’s tapering form supports programmatic efficiencies, from large floor plates at its base for offices to rectilinear floors near the top for hotel rooms. Its boldest feature, the 50-meter-wide portal carved through its upper levels relieves the enormous wind pressures on the building.

Bahrain World Trade Center, Manama, 2008

Two sail-shaped towers, connected by bridges supporting giant wind turbines, put the Bahraini capital on the world skyscraper map. Designed by Atkins, this was the first large-scale integration of wind turbines with a tall building, making a strong, visible statement about the importance of incorporating natural sources of energy production into tall building design. The inspiration for the design came from regional vernacular “wind towers” and the vast sails of the traditional Arabian dhow.

Mode Gakuen Cocoon Tower, Tokyo, 2008

A product of unique spatial constraints, the elliptical Mode Gakuen Cocoon Tower, designed by Tange Associates, houses three different trade schools in one tower, in which three rectangular classroom areas rotate 120 degrees around the inner core. Student lounges are located between the classrooms, facing three directions. Each atrium lounge is three stories high and offers sweeping views of the surrounding cityscape. The tower played a large role in defining the “vertical campus” for the future.

Linked Hybrid, Beijing, 2009

Linked Hybrid, by Steven Holl Architects, presents one of the most advanced contemporary realisations of horizontally-linked tall building networks that have appeared in architectural discourse since the late 19th century. Conceived as a kind of intentional community that would be comprehensive and yet inviting to the greater city. The result is a multi-functional complex with eight skybridge links between nine towers. Each of the skybridges contains a different program, taking on the important social and commercial qualities of a high street literally, at 12 to 18 stories above the ground plane.

International Commerce Centre (ICC), Hong Kong, 2010

As Hong Kong’s tallest building, the International Commerce Centre (ICC) by Kohn Pedersen Fox, houses some of the most prominent financial institutions in the world. It is routinely recognised as a paragon of good management, from a commercial, environmental, and community standpoint. The level of energy efficiency achieved by the ICC is unusual for a tall building, and significant investments have been made in improving energy performance over the years, through more than 50 advanced energy-saving measures.

Burj Khalifa, Dubai, 2010

Burj Khalifa, the world’s current tallest building, designed by Adrian Smith while he worked at SOM, has redefined what is possible in the design and engineering of supertall buildings. By combining cutting-edge technologies and cultural influences, the building serves as a global icon that is both a model for future urban centers and speaks to the global movement towards compact, livable urban areas. At the center of a new downtown neighborhood, Burj Khalifa’s mixed-use program focuses the area’s development density and provides direct connections to mass transit systems. Burj Khalifa’s architecture has embodied references to Islamic architecture and yet reflects the modern global community it is designed to serve.

Marina Bay Sands, Singapore, 2010

Part of a massive regeneration of the Singapore waterfront, the Marina Bay Sands by Safdie Architects is now an indelible icon of the city-state. With three hotel towers supporting a massive “skypark”, topped with public recreation functions and a spectacular infinity pool, the project offers a gateway-like public asset that is truly connected to the network of pedestrian promenades around its namesake marina. The success of the project has inspired similar, and even larger multi-tower, horizontally-connected “mini-cities” in other cities.

CCTV Headquarters, Beijing, 2012

CCTV’s twisting loop shape poses a truly three-dimensional experience, culminating in a 75-meter cantilever. Making extensive use of a continuous braced-tube structural system, the engineering forces at work are rendered visible on the façade through a web of triangulated diagrids that becomes denser in areas of greater stress, and looser in areas requiring less support. Designed by Rem Koolhaas-led OMA, CCTV paved the way for future skyscrapers that would question the very idea of the tall building as a singular monolith.

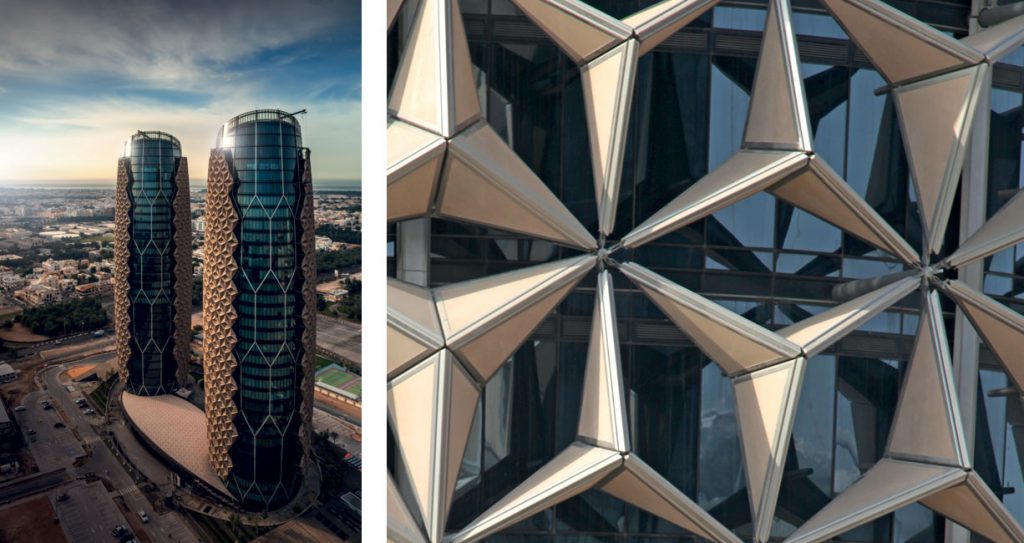

Al Bahar Towers, Abu Dhabi, 2012

Among the most striking façades of any tall building, the operable, clamshell-like array enclosing the Al Bahar Towers by Aedas Architects represents a dramatic approach to resolving the issue of intense solar radiation in the desert climate. The façade’s moveable components are semi-transparent panels, which are combined in arrays much like umbrellas. Each array opens and closes in direct reaction to the sun’s position. While the system improves the comfort and light in the spaces inside, it also reduces the need for artificial lighting and overall cooling loads.

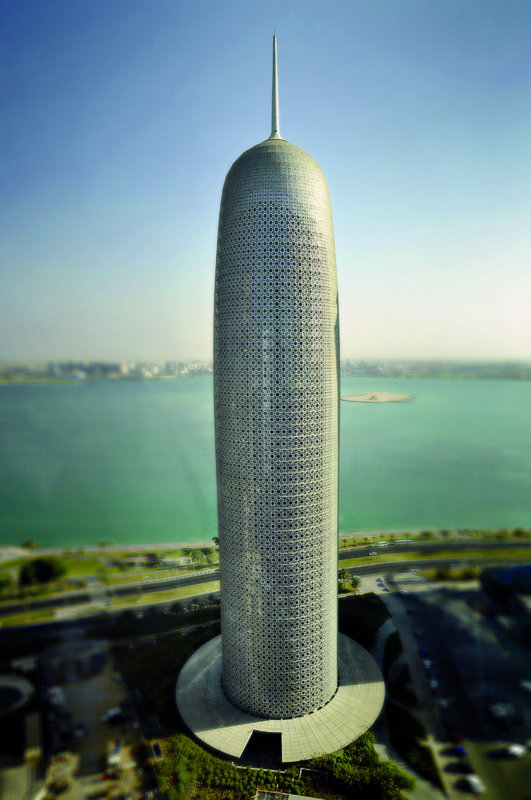

Doha Tower, Doha, 2012

The first skyscraper with internal reinforced-concrete diagrid columns, Doha Tower, by Atelier Jean Nouvel, takes a cylindrical form for its efficiency in floor-to-window area and relative distances between offices and elevators, augmented by an off-center core. The cladding system is a reference to the traditional Islamic shading screen. The design for the system involved using a single geometric motif at several scales, overlaid at different densities along the façade. The overlays occur in response to the solar conditions of each elevation.

Pearl River Tower, Guangzhou, 2013

Using some of the most sophisticated technologies available, the Pearl River Tower, designed by Adrian Smith and Gordon Gill, while the duo was at SOM, was carefully shaped to use natural forces to maximize its energy efficiency. The tower’s sculpted body directs wind to a pair of openings at its mechanical floors, pushing turbines that generate energy for the building. East and west elevations are straight, while the north façade is convex. The concave south side of the building is dramatically sculpted to direct wind through the four openings, two at each mechanical level.

PARKROYAL on Pickering, Singapore, 2013

Parkroyal on Pickering by WOHA is a hotel with a contoured podium that responds to the street scale, drawing inspiration from terraformed landscapes, such as rice paddies, creating dramatic outdoor plazas and gardens that flow seamlessly into the interiors. Greenery from nearby Hong Lim Park is drawn up into the building in the form of planted valleys, gullies and waterfalls. The landscaping amounts to 215 percent of the site area, showing that, even as our cities become taller and denser, we do not have to lose our green spaces.

Shanghai Tower, Shanghai, 2015

Shanghai Tower provides a vision of vertically-integrated space through a sinuous double-skin façade that contains numerous sky gardens, filled with vegetation and the potential for socializing. Upon opening in 2015, at 632 meters it became the tallest building in China, the second-tallest in the world, and one of only three “megatall” buildings of 600 meters or greater height i the world. Its façade and 14-story atria set into nine zones redefine the experience of being in a tall building, and deliver numerous environmental efficiencies.

MahaNakhon, Bangkok, 2016

MahaNakhon means “Great Metropolis” in Thai language. Designed by Ole Schereen, while he was at OMA, it integrates with the city through its organic form, by dissolving the mass as it moves between sky and ground. The dematerialization exercise returns a sense of the human scale to what would otherwise be an imposing structure. It is not short on theatrics, however—a glass-floored observation deck awaits visitors’ ascent to the summit.

Lotte World Tower, Seoul, 2017

Taking inspiration from traditional Korean art forms in the design of the various interior program spaces, the sleek tapered form of Lotte World Tower designed by KPF, stands out from Seoul’s rocky, mountainous topography. The tower is programmed with a great variety of functions, including retail, offices, a luxury hotel, and “officetels”, common in South Korean real estate, which offer studio-apartment-style accommodations for people who work in the building. The top 10 stories contain public entertainment facilities, including an observation deck and rooftop café.